Creating such superomniphobic surfaces is an extension of the natural phenomenon of water-repelling or superhydrophobic surfaces like lotus leaves. A layer of air is trapped beneath the liquid within a microscopic surface structure that makes water bead on the surface and slide off these materials rather than wetting it. ‘This type of superomniphobic surfaces doesn’t really exist in nature,’ says Sergiy Minko from Clarkson University in Potsdam, who led the team.

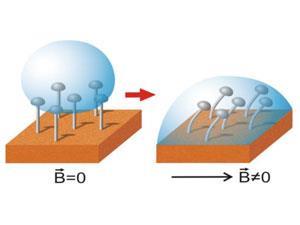

He explains that the difference between a superhydrophobic surface and a superomniphobic one is the overhanging geometry of the features on the surface. An array of pillars or hairs will be superhydrophobic, but adding some kind of overhanging cap – such as the hemispherical heads of Minko’s team’s ‘micronails’ – creates an extra capillary force acting away from the surface. This means it can repel liquids with much lower surface tension, such as soapy water or alkanes.

While a few groups have made variations on superomniphobic surfaces, the team wanted to explore how the angle of the overhang affected the wetting properties of the surface. To do that, they made the micronails from nickel, so that a magnetic field would make them bend over and switch the surface from omniphobic to wettable as the overhang angle changed. ‘This was expected from theory,’ says Minko, ‘but hadn’t been proven experimentally.’

To make the micronails, the team laid a porous polycarbonate film over a gold electrode and used electrochemistry to grow nickel wires up through the pores. When the nickel reaches the top of the polycarbonate, it begins to grow out spherically to make the caps. Stopping the growth before the caps join together, then dissolving away the polycarbonate leaves a forest of micronails behind.

As well as the magnetic switching, it is the simplicity of this process that impresses Joanna Aizenberg from Harvard University, US. ‘These electrochemically-grown nickel micronails are significantly easier to fabricate than previously reported examples of micro-hoodoos [named after columnar rock formations with flat overhanging tops] and nanonails, which were produced by tedious and expensive photolithographic procedures,’ she says.

Being able to easily switch the wettability of a surface could be important when it comes to real-world applications of these materials, Minko adds. ‘Even superomniphobic surfaces can be contaminated – for example with particles blown by the wind sticking inside the microstructure,’ he says. ‘But you can’t just wash a superomniphobic surface – it’s completely liquid repellent.’ Switching off the omniphobic effect would allow the surface to be washed, dried and then returned to its superomniphobic state.

References

A Grigoryev et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2012, DOI: 10.1021/ja305348n

No comments yet