Synthetic biologists have genetically tweaked soil bacteria to make compounds containing chains of three-membered rings that are so energy dense that they outmuscle advanced rocket fuel.

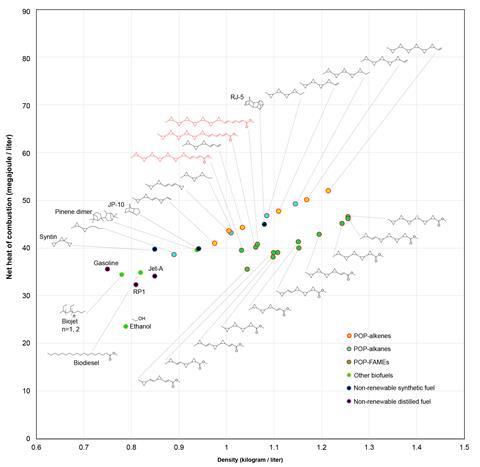

Cyclopropanes boast the largest net heat of combustion per carbon among all cycloalkanes. This is because the three-membered ring forces the carbon–carbon bonds into a 60° angle, while angles in the linear alkenes in gasoline and diesel are at 109.5°. ‘The highest energy density you can get comes from the smallest cyclic compounds, which is a ring of three carbons in a triangle,’ notes Pablo Cruz-Morales at the Technical University of Denmark.

In the 1960s, the Soviet Union developed a synthetic rocket fuel – syntin – containing three cyclopropane rings that offered a 3% increase in impulse compared with kerosene. Impulse represents the thrust per unit of propellant weight flow rate, a concept is similar a car’s fuel efficiency. However, syntin’s synthesis was costly, and involved toxic and hazardous compounds, so production ceased in the 1990s. ‘But it shows that this type of fuel works,’ says Cruz-Morales, who worked as part of a team led by Jay Keasling at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, US. ‘We wanted to make something similar, but with biology.’

The team was inspired by the bacterial antifungal compound jawsamycin, which was named for its five cyclopropane rings that make it resemble a jaw filled with teeth. Keasling’s team studied the original bacterial strain (Streptomyces roseoverticillatus), including an unusual enzyme that forms an olefin in each catalytic cycle, which is modified into a cyclopropane ring.

To create fuel compounds, the researchers re-engineered jawsamycin’s biosynthesis, interrupting it at a step where a nitrogen-containing ring is added onto the cyclopropane chain. They then created a route to fatty acids involving an unusual thioesterase enzyme found in a related bacterium.

The resulting compounds contain six or seven cyclopropane rings along a carbon backbone, dubbed fuelimycins. Just one additional processing step – creating methyl esters – turns the fatty acids into fuel. The esters have a net heating value of around 40MJ/l, which compares to a value of 32MJ/l for petrol and around 35MJ/l for the most popular kerosene-based rocket fuel.

‘These molecules are not produced in nature, but they found a way to make these molecules by bioprospecting different combinations of polyketide synthase enzymes,’ says Michael Köpke, synthetic biologist at LanzaTech , US, which described carbon-negative production of two commodity chemicals earlier this year.

But Keasling’s team only produced 10mg/l of fuelimycins.‘You want to be producing grams per litre, per hour ideally, so there is still some way to go yet [before commercialisation],’ Köpke adds. Nevertheless, he describes the study as ‘impressive’, and says that with the right funding these fuels could one day help power rockets or airplanes.

‘These are exceptional molecules in terms of energy density and specific energy,’ says Josh Heyne, sustainable aviation fuel researcher at Washington State University, US. ‘This has advantages. You can fly further with less weight.’

He notes uncertainty around the impact of these compounds when blended into aviation fuels. ‘It would likely be limited to a certain blend ratio,’ explains Heyne. ‘If a new fuel is developed altogether, then you have to recertify the aircraft.’

Though Streptomyces are today used commercially to make antibiotics, Cruz-Morales says other bacteria such as Pseudomonas or Clostridium could be genetically engineered to feed on biomass residues and thereby generate fuel from waste.

References

P Cruz-Morales et al, Joule, 2022, 6, 1 (DOI: 10.1016/j.joule.2022.05.011)

1 Reader's comment