Clementine Chambon is the 2018 Chemistry World Entrepreneur of the Year for her work using bioenergy to solve environmental, social and gender challenges in rural India

Access to clean electricity is challenging in many parts of the developing world, particularly in rural communities. Oorja, the company co-founded by this year’s Chemistry World Entrepreneur of the Year, Clementine Chambon, is looking to change this.

Chambon was keen to work on renewable energy and contribute to climate change mitigation after she graduated in chemical engineering from the University of Cambridge. A PhD on biofuels at Imperial College London – where she is now a postdoc – seemed the obvious next step. A five-week climate entrepreneurship summer school organised by Climate-KIC in the first year of her PhD, back in the summer of 2014, further fuelled this desire.

Participants were exposed to different aspects of both climate science and entrepreneurship, forming teams to set up entrepreneurial projects, all the while learning how to work as a team, pitch to different audiences and create business plans.

During that workshop, she met Amit Saraogi. ‘We started brainstorming as part of a larger group on how to go about solving the problems of energy access and the irrigation and agrarian crises in India, which are worsened by the effects of climate change,’ Chambon says. The resulting idea was to take agricultural waste and use it to make electricity, and they won the pitching competition.

Chambon and Saraogi were so fired up that they started developing it into an investable company. And Oorja – the Hindi word for energy – was born, with Saraogi as CEO and Chambon as CTO.

‘We started doing more serious market research,’ she recalls. ‘We went to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in northern India to conduct needs assessments, speak with hundreds of farmers, businesses and households suffering from no, or inadequate and expensive, energy supply, and refine our model.’ At that point, the focus was squarely on using biomass gasification to generate electricity, and potentially also biochar for soil remediation and heat for applications such as sterilisation.

A climate fellowship from US organisation Echoing Green, one of the biggest funders for early-stage social entrepreneurs working in this space, gave them funding of $90,000 (£67,000), mentoring and access to their networks to take the idea to market.

Hybrid model

India is a prime candidate for this sort of endeavour, Chambon says. ‘India has the world’s largest number of people living off the grid, so people rely on diesel and kerosene for commercial, agricultural and household purposes,’ she explains. ‘This is obviously polluting, but it’s also very harmful for people’s health, and terrible for the environment. But there is a huge amount of agricultural waste, so it’s an ideal place to do small-scale biomass gasification.’

At first, they were looking at down-draft biomass gasification using residues from crops such as sugarcane, wheat, rice and maize. But it soon became clear that the cost of solar technology was falling dramatically, and they adopted a hybrid generation model instead.

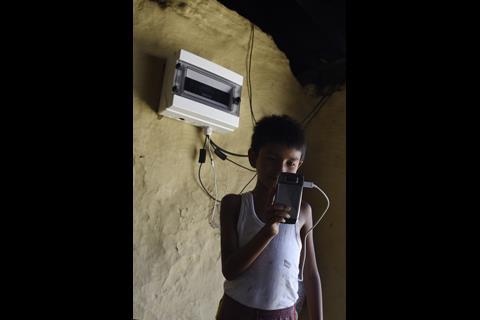

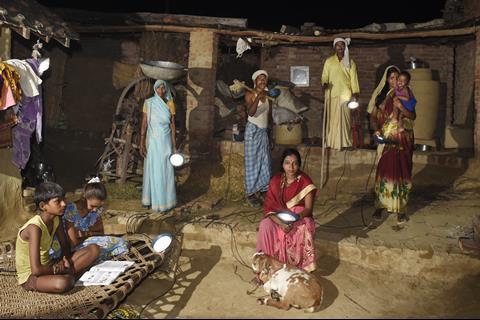

Their surveys highlighted that in completely off-grid places, people were keen for electricity to power fans, lights and phone chargers, but the greatest demand was for energy to run businesses and farms. Ultimately, the hybrid generation model would allow them to set up mini-grids to serve the community’s entire needs – irrigation for farmers, power for small businesses and public institutions, and lighting and phone charging for households.

We want to leapfrog expansion of the national grid by deploying renewable mini-grids in areas where the grid is not yet present

For the pilot project, they realised it would be a lot less challenging to use only solar, because it is technically much simpler to implement, but can be retro-fitted with biomass gasification technology in the future. Gasification will meet the needs of larger businesses who require a constant supply of power through the day, and solar can be used with storage capabilities to meet day and night-time needs for domestic supply. It’s a complex optimisation problem to find the best size and design of mini-grid for each individual community, Chambon explains.

‘We are currently doing due diligence on different types of gasifiers to see which would be most appropriate,’ she says. ‘We are, essentially, project developers. We don’t develop any of the technology components ourselves, but focus on integrating them, site selection, project financing and development, and community engagement. We install the mini-grids, and train local technicians and operators. We also need to understand how big a mini-grid should be for any community, and how demand will evolve with time.’

Mini-grid franchise

They believe electricity access is more of a distribution problem than a technology problem, and Chambon says their business model is designed to address this. ‘Right now, we own and operate the systems ourselves, and are responsible for project development, training and payment collections,’ she says. ‘In future, we are looking to franchise our mini-grids to local entrepreneurs, and transfer asset ownership to them, training their staff to look after the day-to-day operations. That would unlock our capital so we can focus on deploying more mini-grids much more quickly.’

Chambon says a billion people in India do not have access to electricity infrastructure other than individual generators, and there is an investment need of about $45 billion a year between now and 2030 to achieve total electrification. Mini-grids are set to provide about 40% of these connections, according to the global initiative Sustainable Energy for All, and they will be the cheapest option in rural areas.

But there is a risk that climate-unfriendly technologies will predominate. ‘We need to act very quickly so we can outpace the expansion of the national grid, which is very carbon intensive,’ Chambon says. ‘India relies a lot on coal, and we want to leapfrog expansion of the national grid by deploying renewable mini-grids in areas where the grid is not yet present or where supply is weak.’

Oorja is in the throes of evaluating different Indian technological partners. At the outset, they had a partnership with a German company to supply equipment, but relying on imports proved problematic and they are looking to source everything locally. Fortunately, India is one of the world’s leading developers of gasification technology and related components.

Although it is still early days for implementation, they have already identified about 10 more sites for deployment in the next 18 months or so. ‘We are still dependent on grant funding to test different customer segments,’ Chambon says. ‘We have identified five or six fast-growing segments such as irrigation, refrigeration, small-scale manufacturing and agro-processing. We are already active in powering community irrigation pumps, with an identified project pipeline for expansion.’

By summer 2018, they hope to have moved on from modelling to front-end engineering design. ‘For irrigation, we are looking at stand-alone community solutions,’ she says. ‘These are essentially solar pumps that can be added to a mini-grid as the main “productive” load.’ They are due to install one of these in mid-June.

We actively involve women throughout the design process, as they usually know best the house’s energy needs

The day-to-day operation of a mini-grid is challenging, Chambon says, with maintenance servicing and repairs, and the availability of spares all needing to be addressed. ‘It’s like running a mini power plant,’ she claims. ‘A distribution network like the National Grid has quality constraints for constant voltage and frequency, and demands for peak load to be met.’ It’s simple to buy a couple of solar panels to power lights, but a much larger system to run pumps, processing machines or computers, requires a much larger investment.

‘The communities we work in typically have little formal education, but they are critically aware of the constraints that poor energy supply imposes on them, and very clear about their demands for affordable and uninterrupted electricity,’ she says. She cites the example of the solar irrigation pumps that the Indian government has been promoting for the past five years. ‘They have a target of deploying one million pumps by 2020, but have only installed about 60,000 so far. There are a lot of barriers, and even with the capital subsidies available from the government they are unaffordable to anyone other than very wealthy farmers.’

Empowering women

In the future, she says, the mini-grid model has potential in other areas where power is a problem. ‘Large parts of sub-Saharan Africa are a lot less electrified than rural India,’ she says. ‘Uganda, for example, is 85% off-grid, but the population density tends to be lower and solar home systems have taken off massively there. The franchise model could allow us to meet the needs of people outside India, but that’s maybe three to five years down the line,’ she says.

They are also looking to empower women in rural India, who often endure the worst effects of fossil energy by being closer to the fumes all day. ‘One possibility is to involve women’s self-help groups that already exist all over rural India,’ she says. ‘They have the collective ability to save and invest those savings, so they could become a small franchisee. We also actively involve women throughout the design process, as they usually know best the house’s energy needs.’ They are also doing their utmost to recruit and train female technicians, and partnering with NGOs to deliver training programmes, including wPower Hub, an organisation that promotes women’s entrepreneurship in the clean energy sector.

Oorja is currently looking to expand its team from five employees to support the wider implementation of the mini-grids, and there are plans for a fundraising round in 2019 to allow them to move into new customer segments. But for now, they are working on validating those new segments and standardising the mini-grids, both solar only or solar–biomass hybrids, and moving to the franchise model. ‘Our ultimate goal is to deploy 500 mini-grids in the next five years,’ Chambon says. ‘By leveraging this franchise model, standardising everything and packaging the mini-grid so we can deploy it quickly, we believe this is an achievable goal. It would enable us to impact the lives of a million people.’

No comments yet