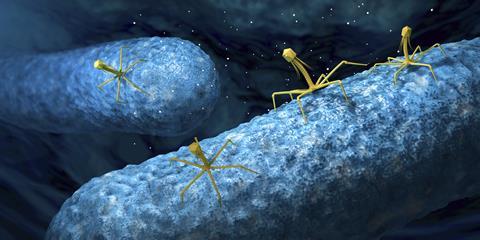

The UK should consider repurposing the mothballed Rosalind Franklin Laboratory in Leamington Spa into a facility for phage research, a cross-party group of MPs has said. Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that kill bacteria and are emerging as an important potential weapon to combat the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). However, more infrastructure and investment are needed to advance research and clinical trials, and support the safe manufacture of phages, according to a new report from the House of Commons science, innovation and technology committee.

‘The Rosalind Franklin Laboratory consists of modern, secure laboratory facilities and was meant to be an important source of national resilience against future pandemics,’ says Greg Clark MP, chair of the committee. ‘But [it] has suddenly appeared for sale on the property website Rightmove, to the astonishment of the science and health communities. Our committee’s report on phages asks for the laboratory to be considered [as a suitable research facility for phages], rather than be lost to the nation and to science in a fire sale.’

Opened in June 2021, the lab was the largest Covid test processing centre in the UK. It was closed in January 2023 and the leasehold put up for sale in November prompting Warwick and Leamington Labour MP Matt Western to call for an inquiry.

The UK Health Security Agency said it was exploring options for the site while ensuring the best value for taxpayers’ money.

Novel treatment

The potential of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections was recognised soon after their discovery over 100 years ago. But they have never been licensed for therapeutic use in the UK, although imported phages have been used occasionally as ‘compassionate’ treatments of last resort. One of the challenges facing phage therapies is that the manufacturing standards that ensure that pharmaceuticals are consistently produced and controlled – Good Manufacturing Process (GMP) standards – preclude UK-produced phages from clinical use.

‘Phages offer a possible response to the increasing worldwide concerns about antimicrobial resistance,’ says Clark. ‘But the development of phage therapies is at an impasse, in which clinical trials need new advanced manufacturing plants, but investment requires clinical trials to have demonstrated efficacy.’

The committee calls on the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to consider allowing non-GMP phages to be produced in the UK for compassionate cases. It also urges regulators to set out requirements for phages to meet clinical trial and GMP standards.

The report found ‘weaknesses’ in the UK’s support for phages in terms of research funding, infrastructure and the networks needed to pull together resources. It calls on the government to establish a shared GMP facility for use by researchers and the health service, and develop a network for sharing knowledge and assets such as biobanks. The committee also urges the government to highlight the role phages can play in tackling AMR, which would help secure research funding and private investment, and recommends developing a body of evidence to demonstrate safety and effectiveness.

Welcome and timely

‘This report marks an important and very welcome step change in the advancement of phage therapy,’ says Chloe James, a microbiologist at the University of Salford. ‘Phages represent a range of promising ways to tackle antimicrobial-resistant infections. However, the approach has long faced multiple barriers and I am pleased to see that these are acknowledged. The report recognises that such barriers could be overcome with new ways of thinking both on how to classify medicines and how to run clinical trials.’

‘This very important and timely report should serve as an urgent call to action for UK Research Councils and the MHRA to support clinician scientists to establish GMP-funded phage manufacture facilities within a regulatory framework to enable clinical trials to be undertaken to assess their safety and efficacy,’ says Debbie Shawcross, a hepatologist at King’s College London. ‘The failure of clinicians to obtain funding for studies involving phages, acknowledged in the report as a “translational phage research gap”, has been driven by a lack of an established regulatory framework and MHRA [requirements]. This is not, however, insurmountable, and clinicians have paved the way by building GMP-manufacture facilities that have enabled treatments such as faecal transplants (which contain trillions of bacteriophages) to be tested in UK clinical trials.’

However, some researchers urge caution on phage therapy. ‘Phage have long been regarded as a possible avenue for development of new antimicrobials, but they are not without shortcomings,’ warns Simon Clarke, a cellular microbiologist at the University of Reading. ‘They can stimulate a patient’s immune system, potentially tipping them into shock or they could simply be quickly removed by the liver rendering them of little use. Bacteria develop resistance to them easily and they are one of the ways nature uses to move around genes which cause bacteria to become resistant to traditional antibiotics, so the widespread use of phage could lead to even more antibiotic-resistant infections.’ He believes there are other, more promising approaches to tackling antimicrobial resistance, such as combining existing drugs or developing drugs that block resistance.

No comments yet