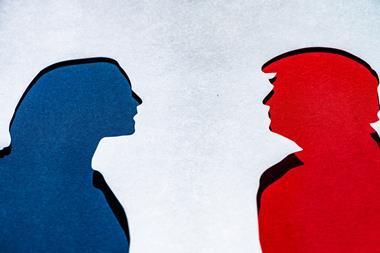

When President Joe Biden beat incumbent Donald Trump for the White House nearly four years ago there was relief within the US research community. This election year anxiety among scientists in the US has resurfaced stronger than ever as Trump runs for president once again.

The prevailing sentiment among scientists and research advocates across the country is that another four-year term for Trump would be disastrous. Representatives from research institutions and scientific organisations, as well as many scientists who have previously served in advisory roles to the White House and federal agencies, are concerned by Trump’s record of slashing environmental regulations, instituting immigration policies that made it harder to attract foreign talent, and demonstrating what they describe as a sustained disrespect for the role of science, data and evidence in policymaking. The response from the chemical and pharmaceutical industry is more mixed with some hoping for less regulatory red tape and others concerned by declining regulatory independence.

Carolyn Bertozzi, who shared the Nobel prize in chemistry two years ago for her development of bioorthogonal reactions, and fellow chemistry Nobel laureate Caltech chemical engineer Frances Arnold say they have not yet heard of an effort by science laureates to endorse Harris for president, as there was for Biden in September 2020 and Barack Obama before him. But Bertozzi speculates that this might happen closer to the 5 November election.

Geeks for Harris

An open letter of support for Harris is, however, being circulated by leaders of the US science and technology community, dubbed Geeks for Harris. ‘We’re doing this to channel our energy into action, to join our voices together and to elevate our community’s values,’ the letter reads. ‘While others want to take our country backwards, Vice President Harris will take us forward to a future where innovation thrives, democracy remains our backbone and every American has the opportunity to contribute to – and benefit from – scientific and technological progress.’ Among the signatories so far are John Holdren, an environmental and climate scientist who was science adviser to President Obama, and Neal Lane, a physicist who served as science adviser to President Bill Clinton and previously as director of the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

Derek Lowe, a US-based drug discovery chemist and former registered Republican who became an independent in 2016 once it became clear that Trump would be the party’s nominee, is all fired up. ‘The biggest thing in my mind is to make sure that Donald Trump does not get into office and does not cause apocalyptic harm to the country I grew up in,’ he says.

Lowe, a Chemistry World columnist, is concerned that Trump and his affiliates have indicated they want to slash as much as possible in the federal government. ‘The only thing that he would see the NSF or the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for are as sources of pork to fund other things he likes,’ he states. During the last presidential election four years ago, Lowe and his wife were prepared to move abroad if Trump was elected. They did not relocate and have now resumed such discussions but haven’t reached any firm conclusions.

The only thing that saved government support for science during the Trump administration was the fact that Congress refused to pass his proposed cuts

John Holdren, science adviser to President Obama

Holdren, currently at Harvard University, calls Trump’s record on science and technology ‘absolutely abysmal’. He says that the former president did everything he could to cut science budgets in virtually every domain except for defence. ‘The only thing that saved government support for science during the Trump administration was the fact that Congress refused to pass his proposed cuts and instead boosted science funding,’ Holdren notes.

In contrast, Biden’s budget proposals for science agencies aimed higher, but weren’t always realised. Most recently, Biden sought to raise the budgets of most non-defence science agencies in fiscal year 2025, but those boosts were dampened by congressional budget cuts for the previous fiscal year, the American Institute of Physics explains.

Hoping good things continue

Although Harris has not yet published an official platform, based on her previous actions as a senator from California and as vice president, the expectation is that she will continue many of the current administration’s policies.

Research agencies should feel pretty confident that we would see money for research continue to be spent under a President Harris

Christine Todd Whitman, Environmental Protection Agency administrator under President George W Bush

‘The budget is not going be good for a long time, but I think her requests are likely to be good for most of the research agencies,’ Lane tells Chemistry World. Christine Todd Whitman, who led the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under former President George W Bush, agrees. She says Harris has always been supportive of legislation to expand R&D. ‘Research agencies should feel pretty confident that we would see money for research continue to be spent under a President Harris,’ Whitman adds.

Under Trump, morale at some federal agencies plummeted, and there was a flood of resignations across key agencies like the EPA. Whitman was disturbed by this mass exodus of scientific and technical expertise. ‘Trump showed a complete disrespect and disregard for science – he cut funding for the EPA considerably, he minimised or grounded the science where he could,’ she says. ‘Morale was in the tank at the EPA because they were being ignored and good science was being pushed aside.’

Holdren and others see signs that Harris would have a forward-thinking science and technology policy. These include her solid support, as vice president, for the Biden administration’s initiatives on climate change and the environment more broadly, as well as her backing of increased funding to address issues of equity in Stem education. As vice president, she has also chaired the National Space Council that advises the White House on the development and implementation of space policy.

Harris’s late mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris, was a renowned biomedical researcher whose work isolating and characterising the progesterone receptor gene helped revolutionise understanding of breast tissue. She worked at several research institutions, including the University of California, Berkeley, and spent the last decade of her research career at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. An immigrant from India, she passed away from breast cancer in early 2009.

‘I would expect Harris, given her background and knowledge, to understand how important basic research is,’ Lane says. ‘So, in addition to a priority on medical research – perhaps the National Cancer Institute and the NIH as a whole – I would also expect her to be positive about the work that the NSF is doing.’

Trouble recruiting scientific talent

During Trump’s presidency it took almost two years to appoint a science adviser with the post eventually filled by Kelvin Droegemeier, a well-respected meteorologist. Droegemeier, who is now special adviser to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s chancellor for science and policy, declined to comment on his experience with Trump or talk about the forthcoming election.

I would expect the China Initiative to come back in another Trump administration – it would be a very politically popular move with his supporters

Neal Lane, science adviser to President Bill Clinton

But Holdren, who knew Droegemeier before Trump appointed him, had several conversations with him afterwards and sheds some light on Droegemeier’s experience. ‘He is a capable scientist, but he was handicapped by having essentially no access to Trump,’ Holdren says, suggesting that Droegemeier virtually never met with the president. ‘He was not able to influence Trump on any of the policy issues where science and technology are germane – he had to do what he could below the level of the president.’

Many fear that it would be even harder for Trump to recruit good scientists now. They note the public disrespect shown by Trump and his allies to the US’s foremost infectious diseases expert Anthony Fauci following the Covid-19 pandemic. Fauci, who has advised six US presidents, has faced verbal attacks and harassment from Trump and several Republicans in Congress and reported that he and his family had been the victim of death threats.

By contrast, Lane and others expect Harris to easily recruit qualified scientists because of the enthusiasm for her in that community.

Trump’s foreign policy history

In one of his first official acts as president, Trump issued an executive order restricting visas for people from several predominantly Muslim countries. This led to prominent scientists and academic groups speaking out, noting that US research institutes host many researchers from the targeted nations and warnings that the directive was already harming US science. The policy, which was widely known as the ‘Muslim ban’, remained in place until Biden rescinded it immediately after taking office in January 2021. During a campaign event in July, Trump vowed to bring back this policy ‘even bigger than before’ if re-elected.

Another of Trump’s programmes that was extremely controversial in the research community, and would likely reappear if he is re-elected, is the China Initiative. He launched the programme in 2018 to counter trade secret theft and economic espionage, but it was widely criticised as racially biased and creating a hostile environment for Chinese researchers at US institutions and those who collaborate with them or host them in their labs.

Biden’s Department of Justice (DOJ) terminated the China Initiative in early 2022 after many of the criminal cases the US government brought against university researchers under the scheme were dismissed. Following a months-long review, the DOJ determined that it was an ill-advised approach.

Lane says the China Initiative did ‘enormous damage’, despite being withdrawn. ‘Our science and technology base is very dependent on young men and women coming from all over the world, especially China, and there are lots of indications that fewer Chinese are coming and increased numbers of China-born scientists in this country who have spent their careers here, are going back,’ he states. ‘I would expect the China Initiative to come back in another Trump administration – it would be a very politically popular move with his supporters.’

A prominent chemist at a large research university in the southern US, who spoke to Chemistry World anonymously, recalls how a researcher in their institution’s chemistry department had years earlier received an offer to collaborate with colleagues in China that was explicitly approved by university higher-ups. However, he faced intimidation and threats once the Trump administration introduced the China Initiative.

‘University administrators turned and went after this chemistry professor and he just packed up everything and went home to China,’ the prominent chemist recounts. They note that the DOJ never actually pursued that researcher, but he fled nevertheless.

Trump’s official platform, Agenda 47, includes no mention of science or research, except for one reference to modernising the military via investment in ‘cutting-edge research and advanced technologies’. But Project 2025, a conservative blueprint for a second Trump administration published by the Heritage Foundation thinktank, does offer some clues.

Although Trump has distanced himself from Project 2025, several of his former cabinet secretaries helped write the plan or collaborated on it. It states, for example, that the NIH shouldn’t be allowed to fund human embryonic stem cell research and that the agency’s ‘woke policies’ that aim to achieve gender parity at scientific conferences it sponsors should end.

‘Project 2025 should be taken seriously,’ Whitman tells Chemistry World. ‘So many of the people who were part of his administration were part of that plan and are still close to him.’

The pervasive sentiment throughout the research community is that Harris is already part of an administration that values scientific research and is working to reverse the damage sustained under the previous president. ‘The Biden–Harris administration has been rebuilding the strength in science and technology in the US government and there’s no doubt in my mind that this would continue with a Harris presidency,’ Holdren concludes.

No comments yet