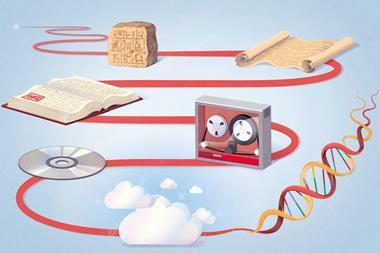

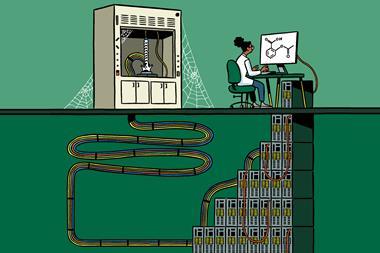

Scientists should be compensated and credited when artificial intelligence chatbots pull information from their papers, a collecting society has said. The call comes amid news that two major academic publishers sold access to their research papers and data to large tech firms to train their artificial intelligence models without consulting authors.

Earlier this month, some authors expressed shock when academic publisher Taylor & Francis sold access to its research as part of a one-year deal with tech giant Microsoft in exchange for £8 million, The Bookseller reported. Wiley, another scholarly publisher, also completed a content rights agreement with a large, undisclosed tech company, the company disclosed at the end of June.

The Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS) collects royalties annually from various organisations around the world including businesses, educational institutions and government agencies on behalf of its over 120,000 members. ALCS’s members include academic researchers, freelance journalists, literary authors, scriptwriters, audiovisual artists and more. This year, ALCS paid out around £44 million to its members.

Unfair use

Now, the collecting society is pushing for its members to be remunerated when chatbots such as ChatGPT use their work. Since ChatGPT surfaced in November 2022, there have been questions around the material the chatbots were trained on and sources the tools pull information from on the internet when answering questions.

‘It’s a very fair request,’ says computer scientist Ed Newton-Rix in Palo Alto, California, who founded the nonprofit Fairly Trained which trains and certifies generative AI companies on respecting copyright holders’ rights. ‘It’s a request that mirrors the demands being made not only across the publishing industry but across really all media industries at the moment.’

OpenAI, which built ChatGPT, and Microsoft, which built another chatbot called Copilot, are facing a number of lawsuits for mass copyright infringement. A number of media outlets have already signed copyright and technology development agreements with OpenAI.

‘It’s a problematic situation that needs solutions,’ says Richard Combes, head of rights and licensing at ALCS. ‘We don’t have a sort of clear regulatory infrastructure around generative AI because it’s quite new and moving fast and always developing.’

The questions the courts will have to consider are whether training AI on studies constitutes copyright infringement because chatbots don’t retain copies of papers in the traditional sense, notes Michael Mattioli, a law professor at Indiana University Bloomington. However, he asks, ‘if it’s copyright infringement, does some defence like fair use apply?’

It’s also true that the chatbots are not usually just regurgitating the content they read, Mattioli notes. Rather, they describe and summarise as best it can what they have read. ‘That’s sort of a distinct issue that might be relevant to scholars.’

According to recent analyses, academics themselves have also benefited from using chatbots to write scientific papers and conduct peer review. A 2023 survey of 1600 scientists found that nearly 30% of researchers had used AI to author studies and around 15% used it to write grant applications and literature reviews.

Compensation consideration

In February, a UK House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee released a report as part of their wider inquiry into generative AI. The report, which ALCS contributed to, emphasised the need to ‘empower rights holders to check if their data has been used without permission’.

The previous UK government had a process in place to bring together rights holders, copyright holders and the tech industry to reach a consensus on the best way forward, Combes says. However, that process was abandoned in the run-up to the election.

Combes adds that the process needs to resume to figure out how to compensate ALCS members for past unlicensed uses and work out an agreement for future licensed uses. ‘We want a framework that’s workable and is accepted by both people developing this technology and also people whose works are implicated,’ he says.

Any future deals struck with tech firms must be based on transparency around how many times a certain work is used so it’s possible to work out if copyright holders are being compensated appropriately, Combes says.

Newton-Rix says generative AI companies should have to make details about the data used to train their tools public. ‘If AI companies are allowed to do whatever they like with any data they like without any consent, you will never solve any of these problems,’ he says. Without consent, he adds, ‘there is no opportunity at all for rightsholders and creators to avoid being exploited’.

An OpenAI spokesperson declined to comment but pointed to a blog post, which notes that the tech firm is building Media Manager, a tool where copyright holders can clarify what content they own and confirm which of their works can be used to train AI tools. OpenAI plans to launch the tool in 2025 and hopes it will become an industry standard.

In June, ALCS launched a survey, asking its members if they would agree to their work being used to train chatbots and answer questions. Combes says he hopes to get feedback from academics given the concerns around the reliability and accuracy of AI.

Combes speculates that researchers participating in the survey may raise concerns about their work being misused, misquoted or referenced out of context by chatbots. ‘The academic community is certainly one that we want to learn from,’ he says.

Editor’s note: The author of this article is an ALCS member but was not involved with the effort to get members compensated for AI uses of their work.

No comments yet