Spiders stretch their silk when spinning their webs. Researchers knew that this was important to strengthen the silk fibres but only now has it been discovered why. A new study reveals, through computational methods, that when silk fibres are stretched after being spun their protein chains align, intermolecular interactions increase and mechanical properties improve. This work could contribute to efforts to optimise synthetic silk production and validate the importance of computational methods, alongside experimental research, in designing silk inspired materials for biomedical and material science applications.

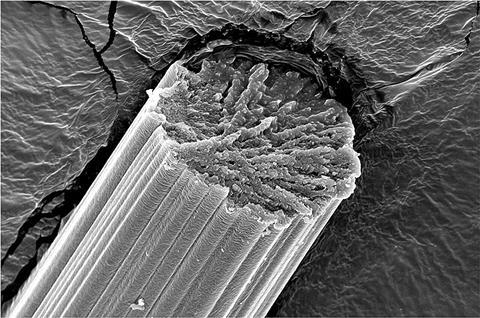

Researchers have long been interested in spider silk, renowned for its strength and toughness, with properties comparable to steel and advanced synthetic materials like Kevlar. However, large-scale farming of spider silk is impractical, energy intensive and expensive making recombinant synthesis a sustainable alternative. ‘Nature has done such a great job of coming up with materials that have really exceptional, finely tuned and specialised properties and spider silk is the strongest organic fibre,’ explains first author Jacob Graham. When spiders spin their webs, they use their hind legs to pull silk threads from their silk spinning organ or spinnerets. This action not only helps the spider release the silk but also strengthens the silk fibres for a more durable web. Experimentalists mimic this process in the lab – called post-spin stretching or drawing allowing the protein to be stretched without compromising its strength. While researchers assumed that post-spin drawing improves synthetic silk performance, the exact mechanisms were not fully understood.

By simulating this action in a computational model, the team from Northwestern University discovered that stretching aligns protein chains within the fibres increasing the number of hydrogen bonds between those chains, leading to stronger, tougher fibres. ‘We showed that by aligning the fibres along the same direction, you get better interconnectivity between the domains of proteins, which form tightly hydrogen-bonded structures with one another,’ Graham says. This computational method allowed the researchers to probe what was happening on the nanoscale and they found that higher molecular order correlated with better performance emphasising the importance of post-processing techniques.

The degree of molecular alignment and interprotein bonding affects fibre extensibility, toughness and strength. ‘There is potential to tune the mechanical properties of the material … the strength and elasticity of the fibre is variable with the degree of post-spin stretching,’ says Graham.

‘You can end up with a crappy fibre if you don’t treat it the right way,’ comments Hannes Schniepp, a spider silk researcher at the College of William & Mary, US. ‘And this paper is about systematically studying the conditions that are going on in a spinner and how can we optimise those.’ He adds that he appreciates the skill needed to simulate the complex protein data and then support it with experiments. This relationship between draw ratio and molecular alignment matched fibre-stretching experiments, highlighting the potential of computational methods to guide further wet-spun synthesis.

‘The long term of our research is to be able to predict what the mechanical properties of these fibres will be using computational methods,’ says Graham. This multiscale approach is crucial in designing scalable and high-performance synthetic silk. ‘This would be pretty promising,’ adds Schniepp, saying that bridging the gap between computational and experimental research could save time and money and ultimately lead to mass production of protein-based materials.

References

JJ Graham et al, Sci. Adv., 2025, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr3833

No comments yet