5.03pm That’s all folks!

Thanks for joining us today. The Nobel prize has been a wonderful showcase for chemistry once more getting phrases like organocatalysis out into the popular press. Congratulations again to the worthy winners Benjamin List and David MacMillan. We’ll be aiming to post our feature providing an in depth dive into the work that won the prize with interviews with the new 2021 chemistry laureates next week so we hope to see you again then.

4.39pm All your questions answered

If you want to know why asymmetric organocatalysis won the chemistry Nobel, how it works and why such a seemingly simple idea was overlooked so long then our explainer is for you.

4.00pm Citations for asymmetric organocatalysis

A quick search on the citation database Web of Science reveals that the phrase ’asymmetric organocatalysis’ has been used in over 5500 indexed publications since David MacMillan and Benjamin List came up with the concept 21 years ago. Citations have been growing rapidly since then.

3.49pm More reaction from the List lab!

We are overwhelmed and over the moon!

— AK List (@ListLaboratory) October 6, 2021

Many Congratulations to Ben🎉🍾 on receiving the #nobelprize #chemnobel @NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/klGtvuHa7m

3.45pm David MacMillan arrives for work!

It’s not just another day at the lab.

— Princeton University (@Princeton) October 6, 2021

Professor MacMillan is enthusiastically greeted by students and colleagues after learning he’s won the #NobelPrize in chemistry. pic.twitter.com/wwgjUhrfGg

2.25pm The children are our future

The seminal 2000 organocatalysis papers from @dmac68 & @ListLaboratory were the 2nd and 1st corresponding author papers from the starting PIs. A reminder to invest in the young!😃#chemnobel

— Dave Leigh (@ProfDaveLeigh) October 6, 2021

Great advice from David Leigh, who himself might have found his name on a chemistry Nobel citation back in 2016. This seems like an appropriate time to plug the op-ed from Natércia Rodrigues Lopes on supporting early-career researchers.

1.10pm Latest news

Our news story has just been updated to fill out some more of the details. We’ll be posting an explainer later today and watch out for our feature length article about David MacMillan and Benjamin List and their work that has changed the face of both lab and industrial chemistry.

12.01pm Holiday snap

It turns out that Benjamin List was on holiday in Amsterdam when he got the call letting him know that his life was going to change forever (at least he was in a timezone amenable to getting the call, unlike David MacMillan, who’s based at Princeton University).

Greetings from Amsterdam!

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 6, 2021

New chemistry laureate Benjamin List sent us this selfie of him and his wife Dr Sabine List on holiday right after they found out the news about his #NobelPrize.

Stay tuned for our interview with him coming soon! pic.twitter.com/lkWNz0B2iP

11.41am Prediction vindication

David MacMillan won a Centennary award in 2019 so that brings the total number of prizes given to chemists that went on to become chemistry laureates to 28. That’s also one for Clarivate and its citation analysis project – they gave a citation award to Benjamin List in 2009.

11.26am List lab lovin’ it!

Celebrations from Benjamin List’s lab. Congratulations to him and all his team members that helped make this happen. It’s a cliche to say it, but it’s true that science is a collaborative enterprise with thousands involved in making and developing every major discovery.

We are overwhelmed and over the moon!

— AK List (@ListLaboratory) October 6, 2021

Many Congratulations to Ben🎉🍾 on receiving the #nobelprize #chemnobel @NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/klGtvuHa7m

11.22am Read all about it!

We’ve posted our news story and will be expanding and adding to it later today (aiming for lunchtime) to bring you more detail. We’ll also be bringing you an explainer that will lay out why MacMillan and List won the prize, what is so important about asymmetric organocatalysis and how it has changed our world.

10.59 Not a total surprise but still…

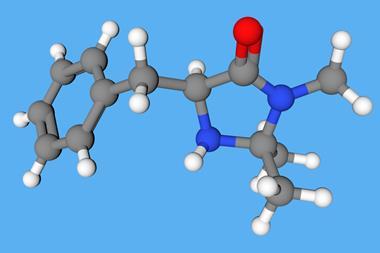

David MacMillan and Benjamin List aren’t a complete surprise but they haven’t been top of people’s lists. We’ve commented on the inherent conservatism of the Nobel committees and how they often reward discoveries long after they made a big impact. The same goes here for asymmetric organocatalysis with the pioneering work over two decades old now. The work of MacMillan and List helped open a new vista in organocatalysis with the creation of catalysts that are selective for one enantiomer – or mirror image molecule – over another. This technology has been applied in everything from drugs to dyes for solar cells. “This concept for catalysis is as simple as it is ingenious, and the fact is that many people have wondered why we didn’t think of it earlier,” says Johan Åqvist, who is chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry. One thing people definitely won’t be saying today is “It’s nice, but is it chemistry!”

10.52am And it’s asymmetric organocatalysis!

Congratulation to the winners Benjamin List and David W.C. MacMillan on their award “for the development of asymmetric organocatalysis”. We’ll be bringing you all the news and views on the announcement as they come in, so stick with us.

10.31am The live feed – some movement in Sweden

10.42am No wait they’re running late!

The announcement isn’t going to be made for another 10 minutes. These delays tend to be because the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences cannot get in touch with one or more of the new chemistry laureates!

10.35am The Nobel Foundation has confirmed that they’re running on time

Expect the announcement in 10 minutes then.

10.30am Eyes on the prize (money)

The science Nobel prizes are the biggest award of their kind when it comes to household name recognition and prestige. But if you are of a more mercenary nature you might want to know exactly how much cold hard cash the top prizes pay out…

10.27am Sweden calling!

Who is getting this exciting call? Find out very soon! #NobelPrize https://t.co/3x0tS1BGKw

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 6, 2021

10.24am An RNA breakthrough rapidly becomes hottest new tip for a Nobel

Katalin Karikó has already been mentioned a couple of times on this this live stream. As one of the pioneers of the RNA technology that has gone on to be used to produce a whole new class of vaccine – mRNA vaccines – that was deployed in record-breaking time in the pandemic, a Nobel nod seems pretty much guaranteed one day. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman have already won a life science Breakthrough prize for their dogged work on RNA technology. (The Breakthrough prizes, set up by Silicon Valley tech billionaires including Mark Zuckerberg and Sergey Brin, are the best remunerated science prizes in the world at $3 million.) RNA therapies were not always seen as a promising avenue, but their perseverance – particularly Karikó who faced a number of professional setbacks for her single-minded pursuit of the technology including demotion – paid off in the end as the world’s first RNA vaccine became a game changer during the Covid pandemic. The pair have now won this year’s Lasker clinical award. The Lasker awards have been running since 1946 and are often a good predicator of Nobel prize success, although the awards are more geared towards medicine so this may be a sign that the chemistry prize is not the one for them.

10.20am More data

If you’ve been enjoying the data analysis you can find more visualisations in our story from 2019, which has been updated to include all the latest laureates.

10.12am Where were the chemistry laureates born and where did they work?

We’ve put together a number of visualisations using data drawn from the Nobel Foundation showing how chemistry has become more international in scope with top chemists moving all over the world to work. When you compare pre and post second world war the difference is stark, but chemistry at the highest level is still focused on Europe and North America. Our fellow hacks over at PhysicsWorld have done something similar for the physics prize too!

10.00am Past performance can predict future performance

The first chemistry Nobel prize was awarded in 1901, but it certainly wasn’t the first scientific prize. The Copley Medal is awarded by the UK’s Royal Society and is the longest continuously running award of its kind in the world, and one that can be given for a discovery in any scientific field. The first was given to Stephen Gray in 1731 for his work on electricity and it’s been given pretty much every year since. But of these longer running and particularly prestigious prizes, which has had the most success when it comes to awarding a researcher who then goes on to win a chemistry Nobel prize?

The Centenary Prize, given by the Royal Society of Chemistry (full disclosure: it also publishes Chemistry World) since 1949, has the best record with 27 awardees who went on to win a chemistry Nobel. This prize rewards ‘outstanding chemists, who are also exceptional communicators, from overseas’. Perhaps being adept at talking about your work is a big factor in getting it noticed and rewarded – something that isn’t always considered when it comes to who wins prizes. The Centenary prize has recognised famous name chemists such as synthetic legend Robert Woodward, unraveller of carbon fixation in photosynthesis Melvin Calvin and inorganic maestro H C Brown before they went on to win a chemistry Nobel. As the years have gone on the number of ‘hits’ has gone down though (presumably the incredible increase in the size of the field and the number of people working in it is a factor), but recent picks that have gone on to win a Nobel include 2016 supramolecular superheroes Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Fraser Stoddart (Ben Feringa, the other winner of the 2016 Nobel has won a Centenary prize but after his Nobel), olefin metathesis chemist Robert Grubbs and lithium-ion battery pioneer John Goodenough. It’s worth noting that the Centenary prize has recently gone to some chemists who have been hotly tipped to win a Nobel, including Omar Yaghi for metal–organic frameworks.

This year’s Centenary prize winners are Jean-Luc Brédas for fundamental understanding of the electronic properties of organic materials, Bin Liu for the synthesis of organic molecules and nanomaterials for biomedical applications and Doug Stephan, for the discovery of frustrated Lewis pairs and their role in catalysis. Given the Centenary’s success in picking work rewarded by the chemistry Nobel committee perhaps we’ll see one of them at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences one day…

In second place when it comes to picking chemists who go on to win a Nobel is the Davy Medal with 22 ‘hits’. Awarded since 1881 by the UK’s Royal Society both this prize and the Centenary prize are specifically for chemistry, while the others shown (with the exception of the Wolf Prize) cast their nets significantly wider over the sciences. As the medal started being awarded before the Nobel prize was even founded a number of recognisable names from the early era of the chemistry Nobel prize are cited. Winners that went on to win a chemistry Nobel include Marie and Pierre Curie, fluorine chemist Henri Moissan and physical and atmospheric scientist Svante Arrenhius. Again, in later years the medal has become less adept at picking out chemists that go on to win a Nobel, only selecting one in the last 20 years that went on win one – Fraser Stoddart.

The Priestley medal, awarded by the American Chemical Society since 1922, takes the prize for awards given after a Nobel is awarded. The Priestley medal has only been given to one chemist that went on to win a Nobel – Paul Flory of penicillin production fame. Another 15 were given to scientists after they’d won a chemistry Nobel. This is not totally surprising though, as the Priestley medal is recognition of a lifetime’s service to chemistry.

Interestingly, number crunchers at Clarivate have given citation laureate awards to eight chemists that then went on to win the chemistry Nobel. Clarivate has been running its citation laureates project for 20 years and picks its winners based on citation data from 52 million article indexed on its Web of Science database. That gives it the best recent record when it comes to predicting future chemistry Nobel winners.

9.51am The Nobel prize ceremony during the pandemic

The Nobel prize medals are usually awarded at an impressive ceremony at the Swedish Academy of Sciences followed by a lavish dinner on 10 December – the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. However, last year the pandemic ensured that there would be no presentation or dinner and Emmanuelle Charpentier received her medal at the Swedish embassy in Berlin and Jennifer Doudna at her home in California. This was the first time since 1956 that the banquet was cancelled – in 1956 it was stopped to avoid having to invite the Soviet ambassador following the invasion of Hungary by the USSR. This year the laureates will once again receive their medals and diplomas in their home countries, and the banquet has been cancelled again.

9.45am Just an hour to go until the announcement now…

We’ll be hosting the Nobel Foundation’s webcast on the live stream and you can of course find it over on their website too.

9.42am Women nominated for recognition

Only 13 women were nominated for the chemistry prize between 1901 and 1966. Austrian–Swedish nuclear chemist Lise Meitner received the second most nominations – 19 in all (plus 29 times for physics). Still, the discoverer of protactinium and nuclear fission never won the prize, although many think she should have. In 1944, the chemistry prize for fission of heavy nuclei went exclusively to Meitner’s long-term collaborator Otto Hahn. One of her staunchest supporters was the physicist Max Planck, who nominated her six times. Despite being opposed to admitting women to universities in general, he made an exception for Meitner as he allowed her to attend his lectures at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin in 1906, the year after she had received a PhD from the University of Vienna. Nevertheless, being a woman, she was banned from the universities’ laboratories until Hahn hired her as an unpaid assistant. The two of them spent many years working side by side until Meitner had to flee Nazi persecution in 1938. Historian Ruth Lewin Sime and colleagues, who examined the Nobel committee’s proceedings when they became public in 1990, suggested that Meitner probably missed out on the prize as a result of disciplinary bias, political obtuseness, ignorance and haste. Meitner was eventually honoured, long after her death, when, in 1996, element 109 was named after her.

9.34am An Ig Nobel beginning

It’s not actually the physiology or medicine Nobel prize that kick-starts Nobel prize season, it’s actually the Ig Nobels – the anti-Nobel prizes if you will. These prizes reward research that first makes you laugh and then think. This year the awards have been given for work on odours produced by anxious cinema-goers, an analysis of cat vocalisations and why pedestrians don’t constantly crash into each other.

9.29am More laureates that never were

In the case of US physical chemist Gilbert Lewis it might have been interpersonal relationships that played a role in him never receiving a Nobel prize, despite being nominated 41 times between 1922 and 1946. The discoverer of covalent bonds and inventor of Lewis dot structures had a habit of making powerful enemies in the chemistry community. He developed a lifelong dislike for Walther Nernst in whose lab he had worked for a year, calling Nernst’s heat theorem ‘a regrettable episode in the history of chemistry’! A few years later, in 1920, Nernst received a Nobel for this work in thermochemistry. Lewis made another enemy in Irving Langmuir, with whom he became embroiled in a priority dispute. Building on Lewis’s and others’ work, Langmuir was mostly responsible for popularising Lewis’s atomic structure theory. Langmuir received a Nobel in 1932, though for different work – surface chemistry. According to one of Lewis’s former students, not winning a Nobel prize was a sore point in Lewis’s life. In March 1946, at the age of 70, Lewis was found dead in his lab, ending any chance of him receiving the prize. Several of his students, however, did end up becoming laureates, including Harold Urey in 1934 and Glenn Seaborg in 1951.

9.23am The subfield race

With Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna winning last year for their work on gene-editing tool Crispr, we’ve updated out chemistry subfield race. It’s pretty clear the direction of travel is all one way now.

9.17am Is it time to change how the Nobels are awarded?

It's #ChemNobel season, or the time of year I plug my @ChemistryWorld op-ed on why the Nobel Prize should be restructured to reflect the collaborative nature of scientific research https://t.co/ET5ZS2R5L8

— sheila ♊︎ (@ululululululate) October 5, 2021

9.08am The laureates that weren’t

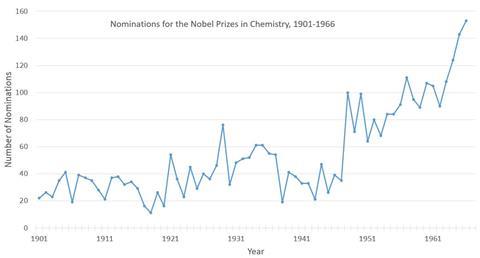

Our senior science correspondent, Katrina Krämer, has been combing through the nominations data in search of noteworthy facts and figures. The nominations process remains closed for 50 years, but that still means that we have data for the prizes from 1901 to 1966 (we’re currently waiting for further data to be released).

Katrina has found that, while the average number of nominations per person in the time between 1901 to 1966 was 13, the number of nominations each laureate received was more than twice that at 35. However, many scientists who never won a Nobel received many times more nominations than people who did eventually end up receiving the prize.

A good example is physical organic chemist Christopher Ingold, who received 72 nominations over almost three decades – between 1940 and 1966. He conducted ground-breaking work on reaction mechanisms and organic compounds’ electronic structure in the 1920s and 30s, introducing concepts such as a nucleophile and an electrophile and reaction mechanism descriptors like SN1 or E2 into mainstream chemistry. Ingold died in 1970 aged 77, so he might well have received the prize had he lived longer. Nevertheless, his legacy lives on as he discovered concepts that remain important to chemists to this day, for example the Thorpe–Ingold effect and the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules. One of the rule’s other discoverers, Vladimir Prelog, did eventually receive a Nobel prize in 1975.

Another person who received more nominations than many laureates was German industrial chemist Walter Reppe. An entire field of acetylene reactions is named after him, although most Reppe chemistry has now become obsolete as the chemical industry has shifted from coal to oil as its main feedstock. The reason he never received a prize despite 64 nominations between 1949 and 1966 might well be because of his close links to the Nazi regime. Reppe worked for IG Farben, which historian Mark Spicka called ‘the most notorious German industrial concern during the Third Reich’. Taming the explosive acetylene, Reppe made it possible to use the gas as a reagent, including in a process to make synthetic rubber. In 1945, Reppe was detained by Operation Paperclip, a secret US intelligence programme that sought to take German scientists and engineers to the US for government employment after the end of the second world war. Reppe, however, refused to cooperate, so he remained in custody in Germany for two years after which he returned to work for BASF, a company reformed when IG Farben was broken up by the Allies at the end of the second world war.

8.58am Nobel predictions webinar

If you’ve got a few spare minutes in the run up to the prize announcement then Chemical & Engineering News and ACS Webinars have also run their usual event to canvass some ‘good natured speculation’ on who might win. This year talking about the prizes and their picks they had on Angela Zhou, a data scientist at CAS, Andrés Cisneros of the University of North Texas, Rigoberto Hernandez of Johns Hopkins University and Frank Leibfarth of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Interestingly, the audience’s favourite was Katalin Karikó, the developer of the technology that made RNA vaccines possible. The rapidly with which the first RNA vaccines for Covid came out certainly wowed everyone, but is it chemistry? Medicine prize perhaps? And is it too soon too for the notoriously conservative chemistry committee? After all, they waited 39 years to give John Goodenough the Nobel nod for developing lithium-ion batteries, a technology enabled by chemistry that is carried everywhere by billions every day. Life without them would be quite different.

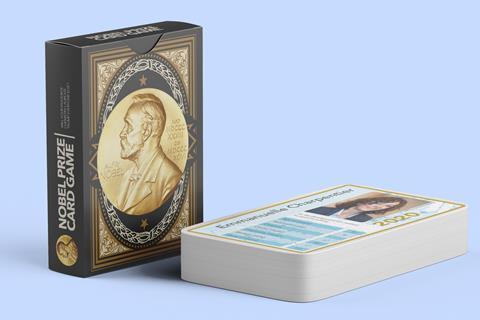

8.49am Pick of the pack

If you’ve got some time in the run up to the prize announcement then give our chemistry Nobel prize card game a whirl. Definitely nothing like a certain top children’s card game, you can play with friends or on your own against ‘Alfred’. Will Roger Tsien edge out Dan Shechtman on citations? Or will Tomas Lindahl beat Emmanuelle Charpentier on the global impact of his work? Give it a go and let us know if you enjoy it.

8.42 am DNA chemistry

Do you know how many chemistry/medicine Nobel prizes have been connected with DNA? The Nobel Foundation has a nice 1 minute run down of all the prizes connected to DNA. There’s a good chance of another DNA related prize this year (although perhaps less likely since gene editing won last year). DNA synthesis techniques is one area that has come up in predictions for a number of years with Marvin Carruthers and Lee Hood the two names most closely connected with this work. The other possible prize connected to DNA is next generation sequencing – something that has made it possible to sequence a person’s entire genome for less than $1000. David Klenerman and Shankar Balasubramanian (we spoke to him last year) have just won the Millennium Technology prize and the Breakthrough life science prize for their work creating the next generation sequencing technologies that have made feats like sequencing Sars-CoV-2 variants rapidly and tracking the evolution of the virus possible. The future of next generation sequencing, where efforts are being made to drive costs down even further and miniaturise the technology, isn’t a field likely to win a Nobel prize just yet, but is one we’ve recently covered.

How many Nobel Prizes are connected with the discovery of DNA?

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) September 27, 2021

Learn about some of the awarded contributions that have been made since the discovery of DNA.#NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/ZNGwidjf89

8.35am Modelling the behaviour of atoms, the climate and… conference attendees?

No one can say that the work of the winners of this year’s physics Nobel prize has no real-world applications!

I'm sure you know all about spin glasses, but did you know Parisi (with Valentina Alfi and Luciano Pietronero) once uncovered a universal law for conference registration https://t.co/BGpsrWBgID

— Andrea Taroni (@TaroniAndrea) October 5, 2021

8.29am Women in chemistry

Last year’s chemistry prize was a first. Never before have two women won the chemistry prize on their own. And that goes for the rest of the science prizes too. (The 2009 medicine or physiology prize was won by two women, Elizabeth Blackburn and Carol Greider, for their work on telomeres, the protective caps on chromosomes, but this prize was shared with Jack Szostak.) Obviously, global attitudes to women in science in 1901 when the first awards were given were rather different to today, with many countries actually banning women from attending universities at all (our Significant Figures series chronicles some of the discrimination women working in science faced and how many overcame it to make serious contributions to our knowledge of the world). But even taking into account that outright sexism and discrimination women faced back then, only four women out of a total of 54 chemistry laureates have won a chemistry Nobel prize in the last 20 years. That legacy of discrimination continues to weigh heavily on science and affects the number of women in chemistry and those that reach the top of their field to this day.

8.23am From the Twitterati

Plenty of chat on the #chemnobel hashtag – you can find plenty of great chemists there that you should follow. It’s going to be a busy morning.

I don’t think it will happen but if the #chemnobel goes to the vaccine that saved the planet, I’m 100 percent okay with that. It’s a good look for chemistry. pic.twitter.com/SANwbFMmIg

— Cathleen Crudden (@cathleencrudden) October 5, 2021

my #chemnobel guess, which is almost always wrong https://t.co/7KAMZ88TCI

— Chemjobber (@Chemjobber) October 5, 2021

An updated version of my #NobelPrize predictions from 2019: three of Aharonov, Aspect, Berry, Clauser & Zeilinger for #Physics; Oganessian or Iijima for #chemnobel https://t.co/6kAZf7GIMl

— Peter Rodgers (@drpeterrodgers) October 5, 2021

Will re-up my dream #ChemNobel trio:

— Matt Hartings (@sciencegeist) October 5, 2021

Harry Gray - Elucidation of the mechanisms of electron transfer

JoAnne Stubbe and Cathy Drennan - Fundamental studies showing ribonucleotide reductase electron transfer pathway

#ChemNobel is around the corner and Prof Yaghi is in my poll. However, I’m expecting many SARS-CoV 2 related prizes https://t.co/5Zi57K1RU6

— Joaquin Barroso (@joaquinbarroso) September 27, 2021

#chemnobel predictions time!

— Laura Howes (@L_Howes) September 23, 2021

Join us next Thursday for some chat about who we think might win. https://t.co/0B0EjkOZkz

8.14am Poll position

And Nature Chemistry editor Stuart Cantrill has run his annual who will win the chemistry Nobel on Twitter. With almost 2500 votes it’s a pretty decent cross section of the chemistry Twitterati.

A month tomorrow (Oct 6th), the 2021 #chemnobel will be announced, so it's time for the annual #ChemTwitter poll! What topic do you think *will* (not should) garner the prize? (Leave comments suggesting what might win if none of the options in the poll...); RTs appreciated!

— Stuart Cantrill (@stuartcantrill) September 5, 2021

8.07am Let’s start with some predictions

As always plenty of polls and predictions for the chemistry Nobel prize. Our news story attempts to round them all up including Clarivate’s analysis basis on crunching citation numbers (more on that later).

Chemistry Views magazine has also polled its readership to see who they think will win the chemistry Nobel. The wisdom of crowds suggests the next winner will be a male medicinal chemist working in North America. Looking at the votes for specific chemists Katalin Karikó, who developed the RNA technology behind the new Covid vaccines, and Omar Yaghi of meta–organic framework fame are in the lead. We won’t have long to wait to see if any of these predictions hit the target.

Sigma Xi, a global scientific society, which was formed in 1886 at Cornell University, has, in recent years, played its own forecasting game. The society has grown beyond the borders of the US and now boasts more than 60,000 members around the world and has counted among its ranks chemistry Nobel laureates Irving Langmuir, Linus Pauling and Jennifer Doudna and many others. Sigma Xi has been conducting a poll that pits fancied researchers off against one another in a knock-out competition with members voting for the winners of each play-off. This year’s winners in chemistry were Omar Yaghi and Makoto Fujita ‘for the development of metal-organic frameworks/coordination polymers and reticular chemistry; for pioneering reticular chemistry’. One of the winners of the physiology or medicine Nobel, David Julius, was featured in this competition but was knocked-out in the first round, whereas none of the physics Nobel winners even got a name-check. We’ll soon see how accurate their predictions are for the chemistry prize.

8.02am Stay in touch

We’ll be tweeting from @ChemistryWorld and you can find us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/chemistryworld. You can also watch the prize announcement made live over on the Nobel Foundation site and we’ll be hosting the video here shortly before the announcement is made. If you’re on Twitter then you’ll want to follow the hashtag #chemnobel. We hope you’ll stay with us too over the next couple of hours in the run-up to the announcement as we’ll be posting some analysis of the chemistry prize, look at who’s tipped to win and some Nobel trivia. We’ll also be running a special all-things-Nobel-prize-related edition of our regular Re:action newsletter later today, rounding up the best of our stories and the rest of the web. If you’d like to receive it later today then sign-up asap.

8.00am Welcome all!

Morning everyone, and thanks for joining us whatever time it is wherever you are. Excitement is building as we get closer to the announcement of the chemistry Nobel prize later today at 11.45am CEST (10.45am BST). Quick recap: we’ve already had two of the three science Nobel prizes – Monday was the medicine or physiology prize and David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian were recognised for their work on how we perceive touch and temperature. And yesterday was physics’ turn with Syukuro Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann and Giorgio Parisi’s work on complex systems at scales ranging from the atomic to the climate getting the Nobel nod. Chemistry is up next and the prize field feels much clearer now two giants – Crispr gene editing and lithium-ion batteries – have won (last year and the year before, respectively). Perhaps we will be in for a surprise this morning. Stick with us as the Chemistry World team will be bringing you all the news and views in the run up to the chemistry Nobel prize and of course after the announcement is made.

You can also find all our Nobel prize stories gathered on one handy page.

No comments yet