4.45pm Another great celebration

Thanks for joining us today. The Nobel prizes have been another wonderful celebration of science and chemistry. Today’s winners well deserve their prize – their work left us amazed when it first came out and it’s been great to revisit it again. Just a reminder that all our Nobel prize stories, including our report on the chemistry prize and the explainer, can be found in one handy place. We’d love you to join us on Friday for a webinar (1500 BST) where we’ll discuss today’s prize with special guests. Next week we’ll also be bringing you a feature-length report on the winners, their work and their hopes and dreams for how it can change the world. We hope you’ll join us for it.

4.17pm Explaining the chemistry prize

We’ve put together an explainer on today’s Nobel prize in chemistry. We’ve tried to answer all the questions that you might have about protein design and structure prediction. Why was protein structure prediction singled out for this honour? Why did the prize also reward the creation of designer proteins? What did the laureates do to earn the top prize in chemistry? Are there any actual uses for this research in the real world? Will protein structure predicting AIs signal the end of experimental techniques to determine structure? We answer all these questions and more.

3.42pm The rise of protein design and structure prediction

We’ve spent a little time mining Web of Science for scientific publications linked to today’s winners of the chemistry prize. Interesting to see the rapid rise of AlphaFold (the tail-off is because we’re only three-quarters of the way through 2024) in comparison with searches related to protein structure prediction and design. With the awarding of the chemistry Nobel prize it seems likely that this already hot area will be turbocharged in the coming years.

3.03pm Collection of papers celebrating the chemistry Nobel prize

The Royal Society of Chemistry has put together a collection of open access papers celebrating computational protein design and protein structure prediction, including four articles featuring David Baker’s work. This collection highlights work on protein design and analysis using computational methods, providing applications in biocatalysis, drug design and more.

2.54pm The Nobel pedigree of this year’s laureates

We had a look at the academic family trees of some of this year’s winner of the Nobel prize earlier today. Now that the chemistry prize is out it’s time to take a look at them too and see if this year’s chemistry laureates have an impressive academic pedigree. David Baker is up first. One of Baker’s ‘parents’ or supervisors was Randy Schekman, who won the medicine Nobel prize in 2013 for work on vesicle trafficking. Among Baker’s ‘grandparents’ he can count Michael Smith, who shared the 1993 chemistry Nobel prize with Kary Mulllis for site-directed mutagenesis and Richard Henderson, who won the chemistry prize in 2017 for cryo-electron microscopy. Arthur Kornberg, 1959 medicine laureate, is another of Baker’s grandparents.

Next up is John Jumper, who was mentored by Karl Freed. Although Freed didn’t win a Nobel prize himself he mentored two winners – Jumper and Moungi Bawendi, one of last year’s chemistry winners. Other than that Jumper has no laureates as his ‘parents’ or ‘grandparents’ but can count Julian Schwinger, 1965 physics laureate in quantum electrodynamics as a ‘great grandparent’. Demis Hassabis doesn’t actually have an entry in the academic family tree yet and isn’t listed under his supervisor Eleanor Maguire at UCL, an oversight that I’m certain will be corrected soon.

2.05pm Why design proteins?

David Baker explains how he hopes to make the world a better place by creating designer proteins.

1.50pm More reactions from the chemistry community

Annette Doherty, president of the Royal Society of Chemistry, said: ’I add my congratulations to David Baker, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper for their remarkable work on protein design and structure prediction, which makes them worthy winners of this year’s Nobel Prize. Chemistry is a science with innovation at its core and the potential to genuinely change our world, and their exciting work is a prime example of that.

’The benefits of this research are remarkable as we can all look forward to applications improving our health and wellbeing. I am sure that their work will prove as inspirational to future generations as the discoveries of their predecessors who have been awarded this most prestigious honour.

’New discoveries and insights, like those unearthed by this year’s Nobel laureates enable progress that benefits us all, as chemical scientists around the world look to create a more open, green and equal environment for us all. Progress in chemistry is a collective and collaborative effort and this award typifies that, so congratulations once more to the winners on this momentous news.”

Mary Carroll, president of the American Chemical Society, said: ’This incredibly complex problem of predicting the 3D structures of proteins from the sequence of amino acids has been one of the biggest challenges in chemistry. We care about this because structure determines function — that’s one of the fundamental tenets of chemistry. The ability to design new proteins goes hand in hand with predicting the structure of proteins,” says Carroll. “The wonderful complexity of proteins has made these formidable tasks, and the solutions have relied on the power of neural networks and sophisticated computational work combined with fundamental knowledge of the underlying chemistry.’

David Pendlebury, head of research Analysis at the Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate, part of the team that correctly predicted Hassabis, Baker and Jumper this year, said: ’We are excited to see David Baker, Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry today. Their pioneering work in protein folding and design has not only revolutionized our understanding of biological processes but also opened new avenues for scientific and medical breakthroughs.

The Nobel Foundation’s selections of laureates in Physics and in Chemistry this year can only be described as bold. The acknowledgment of the transformational role of AI in research in two categories, back-to-back, is unprecedented. The key AlphaFold paper, published in 2021, has already received more than 16,000 citations – that too is unprecedented and reflects the revolutionary impact of this work.

Clarivate named Baker, Hassabis and Jumper as Citation Laureates in September 2024, a recognition grounded in their extraordinary citation records. There are now 80 individuals who have been awarded a Nobel Prize after being identified by the Institute for Scientific Information as Citation Laureates – researchers of Nobel class. This highlights the power of citation analysis to signal the importance of scientific contributions and predict future Nobel laureates.

We extend our sincere congratulations to Baker, Hassabis and Jumper for this well-deserved honour.’

12.39pm The news is in

Our story on how David Baker, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper came to win this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry is in. We’ll be following that up with an explainer on how protein design and structure prediction is changing the world of research and drug discovery and design.

11.59am More reactions coming in for the prize for protein prediction and design

Plenty of excitement about the prize including from 2021 medicine prize laureate Ardem Patapoutian.

A very worthy set of winners. I can now say I've published with a Nobel Laureate!https://t.co/hLWTHDVEy6 https://t.co/1MXhX4bgtT

— Stephen Cochrane (@Cochrane_lab) October 9, 2024

Congratulations to all - incredibly deserved! It was a total and constant honour working with David. His passion for protein design and its applications, as well as his uncanny attention to detail continue to inspire me. And nothing we do today would be possible without AlphaFold https://t.co/iTcfTNDI3A

— Joseph Watson (@_JosephWatson) October 9, 2024

Fab to see Demis Hassibis winning a Nobel.

— Stian Westlake (@stianwestlake) October 9, 2024

Success has many parents, but if you're interested in research funding, it's worth reflecting on the role of David Sainsbury/Gatsby's far-sighted and long-term funding of computational neuroscience in this story.…

Another huge Impact Award! They’ve literally revolutionized our understanding of protein structure in ways few predicted. Congrats! https://t.co/xEV9QoUdAh

— Ardem Patapoutian (@ardemp) October 9, 2024

11.44am First reactions

Here’s John Jumper’s early response to winning the chemistry Nobel prize. Everyone else seems more excited than him!

EXCLUSIVE: The moment John Jumper shares the news about his 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2024

"Glad you guys are all caught up now!" pic.twitter.com/OhNSwiKwgQ

11.39am Stay with us this afternoon

We’ll be bringing you all the reaction from the chemistry community to the awarding of the prize to David Baker ‘for computational protein design’ and the other half jointly to Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper ‘for protein structure prediction’. We’ll also have the full news story and an explainer on what both halves of the prize are all about.

11.29pm A popular prediction

Clarivate selected the three new chemistry laureates this year as one of their top predictions via their citation laureate project – that’s another three ‘wins’ for them to add to the 75 they’ve previously predicted correctly. We expect to hear from Clarivate a bit later, so they’ve got bragging rights on picking out these three. The names of Hassabis, Jumper and Baker have been put about for a few years and they seemed an almost certain pick at some point, but their Nobel nod this year was a surprise for me given how recent their ground-breaking work was and that the physics prize already rewarded neural networks this year. There are still potentially some very worthy winners out there but this year is not going to be their year and given that the committee has rewarded such a recent advance their chances of winning may be fading…

11.08am Split prize

Interestingly this is a split prize for chemistry. One half goes to Jumper and Hassabis and the other half to Baker. The half for Jumper and Hassabis is for their protein structure prediction work with AlphaFold. When I was at university 20 years ago this problem was presented as virtually unsolvable. The fact that such huge strides have been made is incredibly impressive. AlphaFold and its predictions still aren’t perfect but they’re getting better all the time. One other thing about these AI models. We’re still not exactly sure how they come up with the protein structures that they do. AIs are ‘black boxes’ – researchers feed them data to train them but how they reach the solutions that do is unknown. A recent paper suggested AlphaFold was not solving protein structures from first principles but recognising patterns and motifs in protein structures that were fed to it meaning it can be limited if a protein structure it’s been asked to solve is well outside it’s usual dataset.

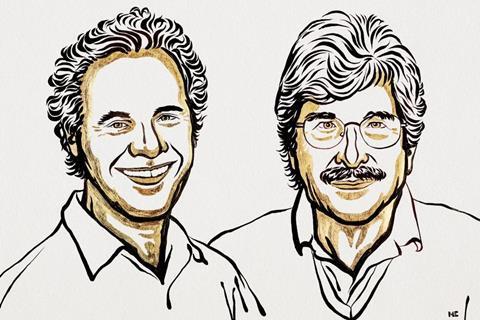

This year’s chemistry laureates Demis Hassabis and John Jumper have developed an AI model, AlphaFold2, to solve a 50-year-old problem: predicting proteins’ complex structures.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2024

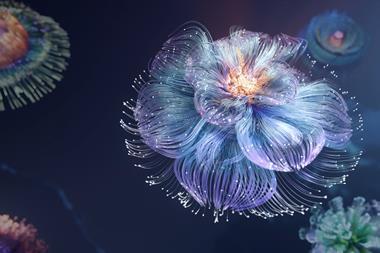

Check out two examples of protein structures determined using AlphaFold2. First up, a bacterial enzyme… pic.twitter.com/ckIiIAGGMX

Baker’s half of the prize doesn’t focus on protein structure prediction, although he has been involved in this, but on actually designing proteins from scratch.

2024 #NobelPrize laureate in chemistry David Baker has succeeded with the almost impossible feat of building entirely new kinds of proteins.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2024

In recent years, one incredible protein creation after the other has emerged from Baker’s laboratory. They range from new nanomaterials… pic.twitter.com/ViwzThsIzf

The way the prize is split means that Baker will receive half of the ~$1 million and Jumper and Hassabis a quarter.

10.59am Not unexpected, but certainly a popular choice

Sometimes the Nobel prize committee springs a surprise on seasoned prize-watchers. This isn’t one of those occasions. The three – David Baker, Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper – have been hotly tipped for some years, having won many of the top prizes in chemistry and biology. Their work has enabled the prediction of the structure of proteins from nothing more than its primary structure – the sequence of amino acids of the protein. Understanding the 3D structure of proteins helps researchers to understand their properties and how they interact with other proteins and molecules. The chemistry prize links into the physics prize from yesterday that rewarded the development of machine learning through neural networks. The three used machine learning and neural networks to develop programs – RosettaFold and Google’s AlphaFold – that could produce highly accurate maps of proteins’ structures. Some winners of the chemistry prize have waited 40 years such as lithium-ion battery pioneer John Goodenough, but the committee note that the important work that led to this prize for protein structure prediction was unveiled in 2018 and 2020.

10.47am Worthy winners

Everyone has been very excited about protein structure prediction and the Nobel committee has awarded the prize very early – they haven’t waited as they sometimes do.

BREAKING NEWS

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2024

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 2024 #NobelPrize in Chemistry with one half to David Baker “for computational protein design” and the other half jointly to Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper “for protein structure prediction.” pic.twitter.com/gYrdFFcD4T

10.44am We’re on time it seems

1 minute!

10.41am Talking about the winners

A reminder that we’ll be running a webinar on Friday afternoon (1500 BST) to take stock of who’s won today and which field was rewarded. We’ll be joined by special guests to talk about the research that won the chemistry prize this year. You can sign up for free.

10.37am Announcement due

The live feed from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has started.

10.35am From the archives

Stories of future laureates that struggled with the subject that would later make them famous aren’t uncommon (see Tomas Lindahl for instance, but Albert Einstein was good at maths at school contrary to myth). Here’s the teacher of cell biologist John Gurdon, 2012 medicine laureate, recounting the time he got two out of 50 on a test and had a ‘disastrous’ term! There’s hope for all students out there.

Despite his teacher’s opinion that he couldn’t learn simple biology, John Gurdon went on to receive a #NobelPrize, for his classic frog experiment, which showed that the DNA of mature frog cells has all the information needed to develop all cells in its body.#WorldFrogDay pic.twitter.com/nHp96fYNDp

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) March 20, 2024

10.30am Nearly there

15 minutes until the expected announcement of the new chemistry Nobel laureates.

10.28am How do you win a second Nobel prize?

Speaking of double Nobel prize winner Barry Sharpless, a bit of Nobel trivia is that only five people have ever won two Nobels – one of them just two years ago, a feat I thought we’d never see the like of again what with the sheer growth in the number of people practising science and the breadth of the scientific enterprise. Philosophy of science researcher Sam McKee takes a look at these five extraordinary people.

10.22am A Nobel puzzle

With just half an hour left before the prize is announced you might want to have a go at our Nobel-themed crossword. If your Nobel knowledge is second to none, our 2024 Nobel prize crossword is just the puzzle for you!

10.18am How it started; how it’s going

After Barry Sharpless won the chemistry prize a couple of years ago – for the second time – I’m enjoying the new picture on the Sharpless lab’s homepage. Before and after!

10.16am Garbage in, Nobel out

John Trant of the University of Windsor in Ontario, Canada, points out that there’s hope for everyone whose experiment hasn’t quite gone according to plan: Charles Pedersen wasn’t trying to make the crown ethers for which he got the 1987 Nobel prize, but they turned up in his reaction in 0.4% yield by accident

An upcoming BANGER of a paper starts: Charles Pederson tried to make bis [2-(o-hydroxyphenoxy)ethyl]ether in 1967, but accidentally synthetized dibenzo[18C6] crown ether in a modest 0.4% yield due to impurities in his starting material. 1/2

— John Trant (@trantteam.bsky.social) October 9, 2024 at 4:35 AM

And if you want more on Pedersen, here’s a lovely personal account of his trip to Stockholm to receive the prize as a somewhat frail 83 year old, written by his stepdaughter’s husband Richard Cleaveland.

10.10am Last year’s leak

Regular readers will recall that last year the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences accidentally revealed the winners of 2023’s Nobel prize in chemistry two hours early. This is believed to be the only time that the winners of the chemistry prize were released early in what is normally a top secret process. In 2010, the winner of the medicine or physiology prize was leaked to a Swedish newspaper, however, after the dossier evaluating Robert Edwards was stolen.

10.07am Decision time

Looks like the committee is meeting and the next winner(s) of the chemistry prize will be decided very shortly.

The committee is now in session to decide the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. We will break the news at 11:45 CEST. Stay with us. https://t.co/6oMXvWRk7Z

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 9, 2024

10.03am Nobel extras

As you might imagine, interviewing 12 Nobel laureates means that you have a fair amount of material that has to be cut. So, while we wait for the prize announcement in just under three-quarters of an hour I’ll be putting out a few of my favourites that we weren’t able to squeeze in.

I was told this story by the president of the Zeiss microscope company in the United States, where he said, you know, we were thinking before your GFP paper, we were actually thinking that we were going to stop production of fluorescent microscopes. And then GFP came out, and all of a sudden, everybody was using fluorescence microscopy. So thank you for helping that part of our company. So the consequences, I think, are very, very broad. You never can predict these things but they continue to fan out and find different areas.

The chairman of the Nobel foundation said, when we were all gathered together, I think it was on our last night at Stockholm, that it had been a pleasure in this particular year of 2016 to host us because we [the laureates] all got on so well together. The inference was that it is not always the case that the new laureates in chemistry, or physics or physiology and medicine or economics are on friendly terms with each other. Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Ben Feringa and I are the best of friends and have been so for a long time. The friendships extend, not just to us, but also to our spouses and to our children and grandchildren.

[Winning the Nobel prize in chemistry] hasn’t really had much impact on me personally. The MRC molecular biology lab has had a lot of Nobel Prize winners, so in a way, it’s just, business as usual. On the other hand, there are demands; the Nobel Foundation is very honourable, it raises the profile [of science] and we’re all in favour of supporting it. So you have to take time out to do activities that you would not have done without [receiving the prize]. That’s a time restraint on what you might really prefer to do, but there is also a sort of moral obligation to do school visits and things like that.

I didn’t have the most pleasant first 20 years at Sheffield without going into too much detail. Indeed, it was so unpleasant that in the mid-point of it all, I took off to the ICI corporate laboratory in Runcorn. It turned out to be one of the best things I ever did for it was there where I came across diquat and paraquat that ICI were marketing worldwide at the time. The fact that the bipyridinium units in these wipe-out weedkillers are redox-active led to our incorporating them into catenanes and rotaxanes and, ultimately, into molecular switches and machines. If I had not had the experience of spending three years at the Heath in Runcorn, I don’t think we would have achieved what we did subsequently as a research group. It was transformative.

The activity of bullying in academia is still going on today. I’m constantly trying to help young people who get caught up in it in different parts of the world. It’s very, very sad that it happens as frequently as it does. I help young people who experience it with a great deal of emotion because I lived it myself. I know the consequences of it happening day-in, day-out, week-in, week-out, month-in, month-out, year-in, year-out. It is far from pleasant finding yourself at the start of your academic career in a situation where you are pilloried morning, noon and night by a senior academic.

9.54am Where do laureates keep their medals?

When we were speaking with chemistry laureates earlier this year, some of them told us where they kept their medals. For security reasons we won’t disclose which laureate said what!

‘Last December, a flood in the basement of my house left the medal unscathed, due to its noble metal composition, but destroyed everything else surrounding [including the case]. The insurance company agreed to pay the astounding cost of replacement that I learned in my subsequent correspondence with Stockholm.’

‘I keep my medal in a safe in a basement.’

‘I thought [the prize] is more for the lab than me. So I gave it to the [Laboratory of Molecular Biology] archive. They’ve got it for now. Fred Sanger gave [the LMB] his two medals and John Kendall left his medal. I’ve given mine in advance; I’m not waiting to die to give it! [The Nobel Foundation] will give you a facsimile medal. It’s gold plated. So I have one of those at home.’

‘It is kept in a safe deposit box (it is solid gold). I do have a replica in my office that I can show to people more easily.

9.48am Haute couture on the lab floor

High fashion and top-flight science might not seem the most likely bedfellows, but the Beckmans College of Design in Sweden has taken inspiration from last year’s prizes to create a range of outfits to ‘explore what laureates, artists and designers have in common’. Apparently, ‘the photographs aim to maintain the playfulness of the creations and, at the same time, elevate them to iconic images,’ according to photographer John Scarisbrick. I’ll take his word for it.

A recap of the prizes last year in case it’s helpful to see if you think the dresses embody the award:

Chemistry – colourful quantum dots for brighter displays

Physics – attosecond pulses of light for studying matter

Physiology or medicine – mRNA vaccines against Covid-19

Literature – John Fosse’s innovative plays and prose

Economics – understanding women’s labour market outcomes

Peace – Narges Mohammadi for her fight against the oppression of women in Iran

9.39am The fate of the Nobel prize medals

Ever wondered what kind of lives Nobel prize medals lead after they’re awarded? For some of them, it’s not just a quiet life gathering dust in a drawer. Some go on to have rather more exciting lives being hidden from Nazis, confiscated by despotic regimes and stolen. And many, particularly over the last decade, have gone under the hammer at auction. We’ve created a data visualisation covering the fate of many of the medals, discovering along the way that they can be worth far more than most would have ever thought possible. There’s a whole lot more in the story on selling off the medals so if you’ve enjoyed stories of medals’ second lives then take a look.

9.28am Ig Nobel science

The award for science that first makes you laugh and then makes you think has been back again this year. The ‘other’ Nobel prize, it rewards the more unorthodox scientific projects such as using drunk worms as a reasonable stand in for polymers when trying to understand how they sort. Other winners this year included the power of painful placebos, pigeon-guided missiles and the suspicious congruence between extremely long-lived people and poor record keeping and pension fraud.

9.24am We’ve got the Nobels covered

You can find all our Nobel prize coverage in one handy place.

9.15am An alternative chemistry laureate…

It wouldn’t be Nobel prize season without satirical takes on the prize. Last year it was Breaking Bad, this year it’s Tom from YouTube channel Explosions&Fire.

The 2024 Noble Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to E. F. Tom for the synthesis of a substituted cubane using chemicals from a hardware store. In a shed.

byu/JImmatSci inchemistry

9.08am 100 years ago…

We have an unusual anniversary being celebrated this year. It’s the centenary of the year that no one won the Nobel prize in chemistry. We’ve got the story of what happened.

9.00am Taking the call from Sweden

‘My wife gave me a poke in the ribs and said “There’s a call for you from Stockholm”’ … ‘a high that I likened to 10 double espressos’ … ‘not a prize for the best scientist, or the smartest’. These are some of the reminiscences of the 12 chemistry Nobel prize winners who spoke to us about what it was like to win science’s highest accolade. They shared some wonderful anecdotes with us on what happened the day they won their prize, what effect this whirlwind experience had on their life and work and the advice they wished they’d been given before they won their Nobel. I’ll just leave you with a vignette from one laureate, delivered with perfect timing, who clearly could have been a comedian too. ‘…It was 2.30am in California, when any sane person is fast asleep. I was asleep too.’

8.56am Odds on favourites

This is an old set of predictions from former avid chemistry Nobel prize watcher Paul Bracher, also known by his nom de plume of ChemBark, but still one of the best in my opinion. He really knows his stuff! Bracher put out this set of odds for the chemistry prize in 2022 and it’s notable that several have won since. Carolyn Bertozzi, Barry Sharpless and Morten Meldal won the chemistry prize in 2022, Louis Brus, and Alexei Ekimov in 2023 and Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman in 2023 (although they won the medicine prize). One researcher given long odds for a prize, Charles Lieber, maybe ought to have his odds increased even further after he ran into some legal trouble.

No time to update, so I’m sticking with last year’s Nobel🏅odds. Just ignore the winners ☺️ and decedents 😔. My personal choice would be for DNA synthesis to finally be recognized. https://t.co/QerOUXn6Th

— ChemBark (@ChemBark) October 2, 2023

8.46am Family connections

Last year we took a look at the academic family tree of laureates to see whether they’re linked to other Nobel prize winners. Perhaps unsurprisingly there does seem to be connection, with Nobel laureates (who usually work at top institutes) mentoring junior researchers that go on to win a Nobel prize. This year, Ambros and Ruvkun were students of Robert Horvitz, who won the 2002 medicine Nobel, alongside Sydney Brenner and John Sulston. And wow, does Horvitz have an impressive list of mentors. He was trained by James Watson (medicine 1962; structure of DNA), Walter Gilbert (chemistry 1980; DNA sequencing) and Sydney Brenner (medicine 2002; cell regulation). And just to add a little more on this topic, Brenner was trained by Cyril Hinshelwood, who won the chemistry prize in 1956. Walter Gilbert is connected to Julian Schwinger (physics 1965; quantum electrodynamics) and Abdus Salam (physics 1979; weak and electromagnetic interactions). Finally, Watson was mentored by John Kendrew (chemistry 1962; structure of globular proteins) and Salvador Luria and Max Delbrück (both medicine 1969; genetic structure of viruses). The genealogy of researchers can be a fascinating topic to delve into and it’s straightforward to make a start.

For the physics prize yesterday’s winner Geoffrey Hinton isn’t directly connected to any Nobel prize winners – he has no laureate ‘parents’ or ‘grandparents’. Equally, John Hopfield has no connections to any Nobel laureates up to his ‘great grandparents’. It may be the branch of physics they work in which has meant they have little linkage to laureates as the physics prize hasn’t recognised many physicists in this field – some physicists were seen complaining yesterday that this was a prize for computer science…

8.37am Crystal-ball gazing

At this time in the morning, we always take a look at who’s the hot tip for this year’s chemistry prize. Number crunchers at Clarivate have been looking at which researchers in chemistry are in the top 0.01% when it comes to citations. Their ‘citation laureates’ this year are John Jumper, director of Google DeepMind, Demis Hassabis, chief executive of Google DeepMind, and biochemist David Baker from the University of Washington. They were picked out for their contributions to predicting protein structure. This work led to the creation of AIs, such as RoseTTAFold and AlphaFold, that surprised the world when they were able to provide highly accurate models of proteins when given nothing more than the protein’s sequence of amino acids. Recent work has suggested that these sorts of Ais, however, aren’t able to predict protein folding from first principles but work off of pattern recognition processes.

Other citation laureates tipped for the chemistry prize were physicists Roberto Car, from Princeton University, US, and Michele Parrinello at the Italian Institute of Technology, for their Car–Parrinello molecular dynamics – a computational technique that enables more efficient simulations of molecular dynamics. Kazunari Domen from the University of Tokyo in Japan, was also selected for his work on light-activated catalysts that harness sunlight to drive water-splitting reactions, a key step in producing green hydrogen. Domen’s work has been influential as his group were able to produce photocatalysts that were able to use almost all the light they absorbed to drive water splitting.

Clarivate has previously had success predicting future laureates by looking at citations, with 75 of their citation laureates going on to win an award at some point – though not usually in the year they’re highlighted. So perhaps don’t expect those above to be winners this year. The Nobel committees that make decisions on who wins a prize have been known to wait decades before awarding a prize – the work by John Goodenough that won him the 2019 chemistry Nobel prize for lithium-ion batteries at the age of 97 was done in 1976.

A poll conducted by ChemistryViews received almost 2000 votes on who its readers think is likely to be the next winner of the Nobel prize in chemistry. Half of voters expect it to be an American biochemist, with most expecting it to be another man too. Out of the many named researchers that readers think might win Chi Huey-Wong is the stand out leader with over 200 votes for his work on synthesis of oligonucleotides. Wong won the 2014 Wolf Prize in Chemistry, often a good predictor of future success (we crunched the numbers last years on which awards are indicators of future success in the chemistry prize). Other top tips (with far fewer votes I note) include next generation sequencing pioneer Shankar Balasubramanian, Karl Deisseroth for optogenetics and biomedical engineer Robert Langer.

Eagled-eyed readers will have noticed a paucity of women in the predictions above (Michele Parrinello is a man too). Women continue to be underrepresented at the top levels of science and this plays out in the Nobel prizes won by women.

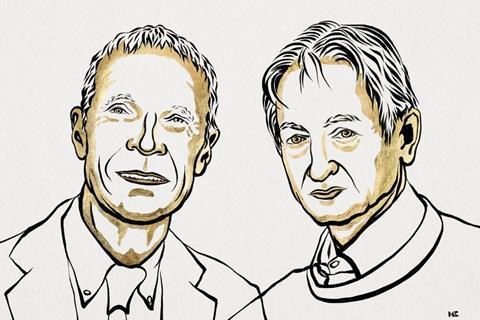

8.24am Who’s won so far?

Before the chemistry prize is announced, let’s recap who’s won the other science prizes so far. On Monday, Victor Ambros from the University of Massachusetts’ Chan Medical School and Gary Ruvkun from Harvard Medical School won the medicine or physiology Nobel prize ‘for the discovery of a fundamental principle governing how gene activity is regulated’. Ruvkun and Ambros, both students of 2002 medicine laureate Robert Horvitz, discovered that microRNAs can control the production of proteins and are another, surprising layer of gene regulation. The pair won the Lasker award for basic research in 2008 alongside David Baulcombe for work on microRNAs. Lasker awards are seen as a good predictor of a future win of the physiology or medicine Nobel prize. Lasker award winners who have gone on to win a Nobel prize in recent years include John Gurdon, Tu Youyou and Thomas Südhof.

On Tuesday, the physics prize went to John Hopfield and Geoffery Hinton for their work on artificial neural networks that many of us use every day on our smartphones when making use of AI for picture editing or intelligent searches. Their work has also led to cutting edge scientific tools such as protein structure prediction programs such as RosettaFold and AlphaFold.

Just the chemistry prize left now, excitement is building with just over two hours to wait!

8.14am: Welcome to Chemistry World’s coverage of the Nobel prize in chemistry

Morning all, anything interesting happening today? Thanks for joining us for the most eagerly anticipated annual event in the chemistry calendar – the Nobel prize in chemistry. I will be your guide to all the news and events in the run-up to the announcement of the prize at 11.45 CEST/UTC (10.45 BST) at the earliest. We’ll be tweeting from @ChemistryWorld and you can find us on Facebook and LinkedIn too and find me at @PatDWalter. If you have anything you think we should share on this live page then get in touch below the line in the comments or @-us on Twitter, sorry I mean X. You can also watch the prize announcement live on the Nobel Foundation site (cameras usually turn on around 11.40 CEST/10.40 BST). If you’re on Twitter then you’ll want to follow the hashtag #chemnobel and #nobelprize for all the latest developments. We hope you’ll stay with us over the next couple of hours in the run-up to the announcement as we’ll be posting some analysis of the chemistry prize, looking at who’s tipped to win and some Nobel trivia. We’ll also be running a special all-things-Nobel-prize-related edition of our regular Re:action newsletter later today, rounding up the best of our stories and the rest of the web. Following the prize announcement, we’ll also be running a webinar on Friday afternoon (1500 BST). We’ll be joined by special guests to talk about the research that won the chemistry prize this year. You can sign up for free.

No comments yet