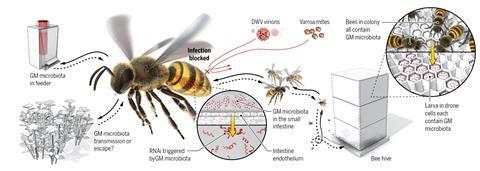

Genetically altering strains of bacteria found in the gut of honey bees appears to protect the insects against two major causes of the colony collapse disorder – Varroa mites and deformed wing virus (DWV). The researchers at the University of Texas at Austin believe that they could eventually scale up production of the bacteria to help protect hives. ‘This is the first time anyone has improved the health of bees by genetically engineering their microbiome,’ explained Sean Leonard, the study’s first author.

The researchers tweaked one strain of bacteria to target the virus and another strain to target the mites. The bacteria were engineered to induce an RNA interference immune response in bees that blocks infection with DWV and actually kill Varroa mites by targeting expression of genes essential for the parasite. Next, they sprayed hundreds of bees in a laboratory setting with a sugar water solution containing the modified bacteria, and the insects fed on the solution as they groomed one another.

Honey bees treated with the bacterium targeting the virus were 36.5% more likely to survive to day 10, compared with control bees. Another set of bees infested with the Varroa mite were 70% less likely to die if they’d been treated with the mite-targeting bacterium than their control counterparts.

‘We have shown that microbiome engineering can increase resistance to pathogens, a strategy proposed for humans and honey bees,’ the study’s authors concluded. They noted that the risk of the modified bacteria escaping into the wild and infecting other insects is ‘very low’ because the bacteria used are highly specialised to live in the bee gut and can’t survive for long outside of it. These bacteria are also protective for a virus that strikes only bees.

Lena Wilfert, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Ulm in Germany who was not involved in the research, agrees that addressing Varroa and DWV is important to improve the health of honeybees and wild bees. She describes the study as ‘very exciting’ because they demonstrate a new route to study bee genetics, and may be a novel way to control Varroa and DWV infections. She adds that preventing habitat loss and abiotic stressors such as pesticides will also be crucial to protect honey bee populations.

Wilfert says it will be important to test whether the effects are stable across generations as honeybees acquire their microbiome vertically from nest mates. She points out that it is possible the virus or mites could quickly evolve resistance, or that these genetically modified bacteria could spread to wild bee species, which have a very similar gut microbiome.

Quinn McFrederick, an entomologist at the University of California–Riverside, agrees that the bacteria are likely to be host specific, as experimental transfers between honey bee and bumble bee microbes usually failed. He warns, however, that much more testing would be required to ensure that these engineered microbes stay in their host and do not transfer to other insects.

1 Reader's comment