Political uncertainty risks UK losing out to China, US and EU

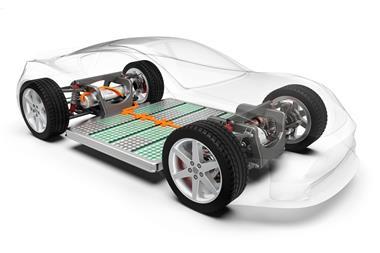

The collapse of battery startup Britishvolt has highlighted the precarious position of electric vehicle battery manufacturing in the UK. Vehicle manufacturers ideally need local battery supply chains in place to minimise costs, but uncertainty over political support is deterring investment, say industry observers.

After running out of funds in mid-late 2022, Britishvolt scrambled to attract enough investment to continue operating. It eventually entered administration in January, with most of its 300 staff made redundant. At the end of February, Australian firm Recharge Industries agreed to buy the firm’s assets and technology and take on its remaining employees.

Britishvolt had aimed to open its first £3.8 billion gigafactory in the north of England, with construction at the Northumberland site begun in 2021, and had trumpeted plans for a second factory in Canada. The UK government had heaped praised on the company and promised £100 million in support if key milestones were reached, but when the firm ran into financial difficulties last year, the government refused to grant early access to its promised funds as its conditions had not been met. Work at the former power station site in Blyth had barely started.

Britishvolt attracted controversy in the press over how it spent its money, and remained far short of its investment targets. ‘I was always sceptical about the company,’ says David Bailey, professor of business economics at the University of Birmingham, UK, and authority on the UK automotive sector. ‘They had no track record in developing technology and it was never clear where this £3.8 billion was going to come from.’ A third problem, he adds, is that it had no big customer agreements lined up to buy its batteries and secure steady revenue.

Unless the UK makes batteries at scale, it won’t have a mass car industry

But battery experts also criticise the government’s offhand approach, emphasising that similar roadblocks remain for prospective battery makers. Moreover, an absence of domestic battery manufacturing could essentially sink the UK’s car industry, which accounts for 10% of total exports and employs 182,000 people.

EVs booming

UK car production fell almost 10% year-on-year in 2022, to around 775,00 cars. That figure is a long way from the recent high of 1.5 million in 2016, and was partly due to chip shortages and negative macroeconomics. That said, battery electric and hybrid electric vehicle production rose 4.5% to 234,000 last year, representing almost a third of all car production, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

UK electric vehicle sales are growing much faster than production. Sales of new battery vehicles rose by 40% in 2022 to over 267,000, but most of those were imported. With the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles set to end in the UK by 2030, sales of electric vehicles are expected to continue growing strongly. Without significant growth in battery manufacturing, however, it is unlikely that many more electric cars will be manufactured in the UK, as batteries are heavy and expensive to transport. Moreover, according to EU–UK trade rules, a battery must originate in the UK or EU for the vehicle to avoid tariffs on trade from 2026. This is an added incentive to build battery gigafactories locally, but the UK is falling behind.

‘Unless the UK makes batteries at scale, it won’t have a mass car industry,’ says Bailey. The ‘build it and they will come’ approach failed for Britishvolt, he adds: a rational strategy would see the government work with car makers and attract a variety of battery manufacturers to serve the UK industry.

There’s a reluctance to invest in the UK because of the uncertainties. If you don’t have a strategy for electric vehicles, then you will not have a battery supply chain

‘It is a chicken and egg situation,’ says Billy Wu, battery chemist at Imperial College London, UK. ‘You need gigafactories to attract car makers to the UK, but there is hesitation.’ Factories require significant capital investment, and profit margins in battery manufacturing can be tight. ‘Because this requires long-term commitment and capital,’ says Wu, ‘uncertainty in the UK in terms of policy is really a deterrent [to battery makers].’

Other UK companies have attracted attention, only to disappoint. London-headquartered Arrival began building electric vans at a facility in Oxfordshire in 2022; last October it revealed that it would refocus attention towards the US market, encouraged by subsidies available through President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, and open a factory in North Carolina. The firm recently told investors it would halve its global workforce to 800 employees to save on costs.

Given the large amounts of capital investment required to set up gigafactories, government needs to be clearer and more proactive with its policies if it is to appeal to battery manufacturers, say industry observers. ‘The government plucked 2030 [to halt combustion engine vehicle sales] out of thin air and never bothered to produce a strategy to get there,’ says Bailey. ‘Brexit [also] caused a lot of uncertainty, which stalled investment in the auto industry, including in new battery technologies,’ he adds.

With relatively few potential bulk buyers for vehicle batteries in the UK, investment incentives and a stable, supportive policy environment will likely be needed to develop a robust domestic supply chain. ‘There’s a reluctance to invest in the UK because of the uncertainties,’ agrees Robert Steinberger-Wilckens, a chemical engineer at the University of Birmingham, UK. ‘If you don’t have a strategy for electric vehicles, then you will not have a battery supply chain.’

Falling behind

Britishvolt has been compared unfavourably with Northvolt, a Swedish battery manufacturer that successfully partnered with carmakers such as Volvo, BMW Group and Volkswagen. It promises to source raw materials to international standards and reduce consumption through recycling. Meanwhile, Jaguar Land Rover is rumoured to be deciding between the UK and Spain to make batteries at scale, says Bailey.

The government seems to think it should leave it to the market, but that’s not what’s happening in the US, or the EU or China

Other countries are zooming ahead. ‘If you look at China, they have been subsidising battery making for a very long time,’ says Wu. And the US Inflation Reduction Act enacted in 2022 offers billions of dollars in tax credits to electric vehicles in the US – but only if 40% of their components by value are extracted or processed in the US, or trade partners, by 2024. This figure rises to 80% by 2027.

In the EU, the European Battery Alliance launched in 2017 aims to make Europe a global leader in batteries. The European commission began consulting on relaxing state aid rules in February, partly in response to the US legislation. ‘The US intervention is a game changer,’ says Steinberger-Wilckens.

Around 35 gigaplants are built or under construction in the EU. A Faraday Institution report in 2022 projected over 1100GWh per year of battery production capacity in Europe by 2030, with over 40 factories expected to be operational by then. This projection has more than doubled since the institution’s previous report in 2020. It pointed to Germany as a leading location – with 12 gigafactories open or planned – along with Hungary, France and Italy. But even with this surge in construction, Europe has a long way to go to compete with China, which manufactures around 75% of global lithium-ion batteries, with Europe making perhaps 7%.

For the UK, demand is forecasted at 100GWh of batteries per year by 2040, requiring around ten gigafactories, according to the Faraday report. Of that, only 1.9GWh/yr of capacity is currently operational – run by Envision AESC and supplying Nissan’s Sunderland car plant. Nissan and Envision AESC have agreed to build a second, 11GWh/yr plant in Sunderland, which is due to be completed in 2024 and could potentially expand to produce 25GWh/yr by 2040.

National ambitions

While loosening state aid rules was heralded as a Brexit benefit, aid for the UK battery industry seems to be lacking. ‘The UK is really out of sync with what’s happening around the world,’ says Bailey. ‘The government seems to be standing on the sidelines, watching.’ UK industry also lost access to the European Investment Bank when it left the EU, which previously provided R&D funding for Ford and Jaguar Land Rover in the UK. A UK Infrastructure Bank, announced during the government’s 2021 Budget, is not yet in first gear.

UK battery science is world-leading, but commercialisation remains a sticking point. ‘The UK has invested a lot of money, but it is always project oriented,’ complains Steinberger-Wilckens. ‘There’s no market introduction programme.’ Bailey is critical of government inaction. ‘The department of business seems to think it should leave it to the market, but that’s not what’s happening in the US, or the EU or China.’

You could see a future where we don’t have enough battery cells. That could really slow down national ambitions to decarbonise

BloombergNEF recently placed China top of its lithium-ion battery supply chain rankings. Canada rose to second, followed by the US, Finland, Norway, Germany, South Korea and Sweden. The UK ranked 12th overall, but was 15th in terms of battery manufacturing and joint last for access to raw materials.

Electrification of transport and other emissions reduction activities could suffer if the UK doesn’t get its act together. ‘It goes back to energy security. If you don’t control that part of the supply chain, you are at the whim of other countries’ agendas,’ warns Wu. ‘We are forecasting a shortfall in cell manufacturing, so you could see a future where we don’t have enough battery cells. That could really slow down national ambitions to decarbonise.’

During a debate in the UK parliament in January, Graham Stuart (then minister of state in the department for business, energy and industrial strategy) said that the government would take steps to champion the UK as the best location in the world for automotive manufacturing. He noted investments by Nissan, Stellantis and Ford, and lauded the automotive transformation fund, which supports large-scale industrialisation. However, Labour’s shadow secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy, Jonathan Reynolds, warned that [battery] factories ‘are being built in competitor countries, and that is because they have governments with the vision and commitment to be the partner that private firms need to turn these factories from plans on paper into a reality.’

2 readers' comments