Sharp drop in grant numbers hits young scientists and blue skies research

Senior researchers have warned that a sharp drop in the number of research grants awarded this year risks damaging UK chemistry.

Young chemists applying for first-time grants have suffered most under widespread changes to the funding strategy of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). In the half-year since April 2008, EPSRC has funded 4 and rejected 17 ’first grant’ chemistry applications: a success rate of under 20 per cent. In the last financial year, EPSRC funded 18 out of 25, or 72 per cent, of first grant applications.

Meanwhile, the proportion of chemistry grants funded through ’responsive mode’ applications - where scientists can submit proposals on any subject for any amount - has dropped from around 25 per cent to below 10 per cent.

The sharp fall in first-time grants could undermine young researchers at a crucial time in their career, leading chemists say. ’This is a major blow to the community - new academics are our future,’ says Robin Perutz, an inorganic chemist at York University and president of the RSC’s Dalton Division. ’New academics have gone through hundreds of hoops to be singled out as capable of running independent research groups, and we should give them that independence and not make them beholden to a patron. That’s the strength of the UK system over those in Europe.’

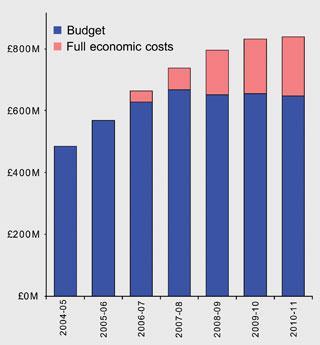

The drop in grant numbers comes because each award is worth more money: EPSRC has scrapped a limiting cap in order to make sure, under a programme of ’Full Economic Costing’ (FEC) agreed by all research councils, that each grant includes money for university overheads. The four grants awarded this year are worth an average ?367,000; last year’s 18 were worth ?261,000 on average.

’The result is a small number of people scoop large first grants, and the majority get nothing,’ says Jeremy Sanders, former head of the University of Cambridge’s chemistry department. ’Given that those applying have just been successful in appointment competitions, that does seem profoundly unsatisfactory.’

EPSRC admits that the drop in success rates for young applicants is a ’real concern’. ’On 14 October EPSRC Council agreed the need to introduce measures to make sure we can properly support people starting out in their academic career - within the constraints of the funding we have,’ Lesley Thompson, EPSRC research base director, told Chemistry World. Measures being considered include putting a cap back in place, or asking universities to top up funding - allowing the research council to award more grants, she said.

Shifting sands

Chemists are also concerned that a change in EPSRC funding strategy has been introduced too quickly. Around 20 per cent of funds have been set aside for priority areas, such as energy and next generation healthcare, and the EPSRC is currently consulting to identify ’grand challenges’ that will affect the chemistry community over next 20 to 40 years.

EPSRC says money set aside for these targeted priorities can go to fundamental research as well as to highly applied projects. But many chemists are not convinced.

’Responsive mode is the heart of science,’ says Donna Blackmond at Imperial College London. ’Diverting money to these "important challenges" threatens research based on the individual scientists’ ideas, which is how big things get discovered.’

Sanders agrees: ’Top-down initiatives might be a good way of translating fundamental science into applied technology, but I remain to be convinced that they’re a good way of discovering fundamental new science.’

Alongside these initiatives, EPSRC has decided to focus on funding multi-disciplinary teams in large research programmes, for up to six years. Inevitably, this means EPSRC must dole out fewer, larger grants, because its budget has remained flat once FEC is taken into account.

’The sudden shift in funding has been a short, sharp shock for academics, and there’s a large degree of mistrust about where this is coming from - with the research councils viewed as a spokesperson for the Treasury,’ says David Fox, senior director in discovery chemistry at Pfizer and currently industrial fellow at the RSC.

Brokering the peace

’Right now the perception in the community is that there’s no money, and there’s also a perceived assault on responsive mode funding,’ adds Lee Cronin, a professor of chemistry at the University of Glasgow. ’In the last five years, EPSRC has positively invested in chemistry and we are now poised to do great things - but by pushing through a generation’s worth of changes in under a year, they jeopardise that investment. They need to engage with us more positively, because chemists could make the biggest impact in energy, sustainability, and health - we have all the tools in our toolbox.’

The RSC council met with EPSRC on 2 October, in a bid to broker improved relations between chemists and the research council.

Richard Pike, the RSC’s chief executive, stressed that chemists should look more closely at the funding available from EPSRC, particularly looking to priority research areas such as energy.

’Some of the key challenges we have facing us are going to need to involve many people in coordinated research, although we mustn’t lose sight of the importance of small groups doing highly innovative work - its all a question of balance,’ Pike says. ’But I do think the community has become somewhat polarised in not recognising the full opportunities available that it really should jump at. If chemistry can show it can contribute positively towards these urgent issues such as energy, then that is to the benefit of the whole community.’

’I’d like to see if industry could act as a lightning rod for academics and EPSRC to come together to hammer some of this out, because at the moment it seems to be a bit of a stand-off,’ adds Pfizer’s Fox. ’Perhaps then some of the barriers towards engaging in these grand challenges might be lowered.’

James Mitchell Crow

No comments yet