Electrifying process heat is a cost problem, not a technical one

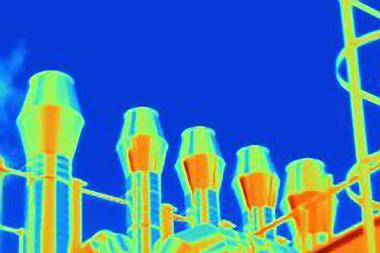

Several segments of the chemicals industry are often described as being particularly difficult to decarbonise – often owing to their high demand for energy, particularly heat. This heat is predominantly supplied by burning fossil fuels, but technology already on the market could theoretically electrify around two thirds of industrial heat demand. That figure is expected to rise to over 90% within the next decade as nascent technologies grow and mature.

That means we should stop thinking about process heat so much as a technical problem, and think of it more as a cost and infrastructure problem. The solutions exist, but we’re either not prepared to pay for them, or there are other structural barriers to implementing them – like upgrading the capacity of electrical grid connections to supply the energy that once arrived in coal trucks and natural gas pipelines.

Nor can we rely on market forces alone to provide the financial incentives to implement these changes. There are very few cases (yet) where customers are willing to pay a premium price for a product that is chemically identical to that of another supplier, apart from the associated greenhouse gas emissions.

But the costs are not fixed. Heat pumps, electric boilers, heat batteries, electric arc furnaces and other low-carbon heat sources are already getting rapidly cheaper to buy and to run. And most will continue to get cheaper as we advance our knowledge and bring economies of scale to bear. Eventually, in many cases, it should be possible to undercut fossil alternatives on purely economic grounds.

But that takes time. And given the long lifespan of chemical plants and the cycles of investment in new ones, it is time we don’t have if we are to reach climate goals set for 2030 or even 2050. Saying something is ‘too difficult’ can become an easy excuse for inaction. If it’s ‘too expensive’, then we can find ways to make it cheaper. To tip the balance, we can choose to make high-emissions options more expensive – for example by taxing carbon emissions; or make low-carbon technologies cheaper through subsidies, supporting technology development and removing infrastructure impediments. Or both. Change doesn’t come for free, but we have the possibility to make the price worth paying.

No comments yet