Chemists give advice for bridging the divide between chemistry and engineering

Chemists give advice for bridging the divide between chemistry and engineering

To a large degree, the differences between chemists and chemical engineers are driven by our current education system. In terms of the deficiencies of chemists, there is some truth in the charge that we don’t think quantitatively enough. It doesn’t help that physical chemistry is taught in the undergraduate course as a stand alone element and not in the context of what a practicing organic chemist needs to know.

The UK chemical engineering degree seems to be tailored for the oil and gas industry. This is for good reason, as that’s where most of them will get jobs. However the ones that end up in the pharmaceutical industry are under-prepared in both the basic scientific method of hypothesis testing and also in practical skills. This causes many of the communication issues alluded to in these lists of ’ten things’. Firstly, there is a disconnect between the chemist who is trying to understand what’s going on from a fundamental mechanistic view, and the engineer who needs some numbers (data) to plug into his/her equations. What tends to happen is the engineers ask if they can help, followed by a request for the chemists to do a whole host of experiments to generate the data the engineers need in order to help. This is compounded by the fact that many UK engineers lack the practical skills to generate the data themselves. The conversation is quickly terminated by the chemist who says they don’t have time.

So, in the pharmaceutical industry, you have very busy chemists who are well versed and happy with the semi-quantitative world of mechanistic organic chemistry, who are being, to their minds, ’pestered’ by engineers who need more quantitative data but can’t guarantee a solution. It’s not surprising that this relationship doesn’t always work out for the best.

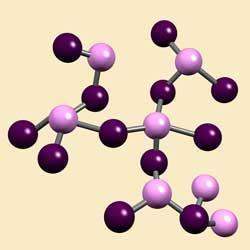

1. Chemical structures matter

How hard can it be to choose a replacement compound for a particular application? Sadly, small changes in the structures of organic compounds can have huge effects on properties. Different isomers of compounds can react quite differently and can have quite different physical properties, such as toxicity and smell. Chemists often intuitively know some (but not all!) of these effects, but can’t understand everything about what gives a compound its particular properties. No wonder there are surprises.

2. Chemists are in danger of being overwhelmed by vast numbers of compounds

So many compounds have been discovered - and so many more lie undiscovered - that chemists are totally overwhelmed. Many of their models, rules and theories do not universally apply to all compounds. But with knowledge of their limitations, these tools can be invaluable in bringing some order to an otherwise jumbled mass of facts.

3. Trust a chemist’s intuition

Data-demanding engineers should remember that chemists can have a good idea of how a compound will react even if all of the kinetic and thermodynamic data are not available - chemical intuition is important.

4. Chemistry isn’t only qualitative.

Chemists can look at things quantitatively too; computational chemistry has made remarkable advances in recent years. Computers can help to predict properties of simple compounds without even making them.

5. ...but chemists prefer experimental verification

There are so many exceptions to these predictive methods that chemists are loath to accept the results of calculations without experimental verification. Most have a healthy scepticism about calculations. This often makes chemists take less rigidly defined positions than engineers when discussing problems.

6. Don’t underestimate analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry and spectroscopic methods are hugely important, but sometimes don’t seem so obvious to our engineering colleagues.

7. Chemists are not anti-automation

Most chemists do appreciate the need to automate chemical reactors in many areas.

8. Chemists are friendly!

Chemists interact very effectively and profitably with many disciplines; medicine, pharmacy, biology, material science, astronomy. And engineering.

9. Disconnect isn’t global

In general we find that chemical engineers in Europe and the US know a lot more chemistry than their UK counterparts. This seems to be because less chemistry is included in the curricula of most (but not all) chemistry engineering courses in the UK.

10. Education points the way

Many chemists are really keen to collaborate with chemical engineers; some of the grandest challenges facing humanity can only be solved by such interaction. Shared appreciation and education is vital. The University of Nottingham’s Dice (Driving innovation in chemistry and chemical engineering) project intends to show the way!

This article is based on discussions between Martyn Poliakoff and Steven Howdle at the University of Nottingham, and David Lathbury at AstraZeneca

Published in conjunction with the Institution of Chemical Engineers’ magazine The Chemical Engineer

No comments yet