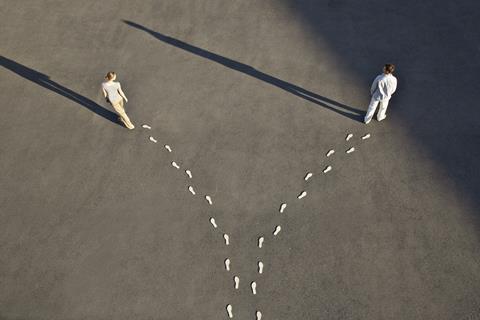

If the UK leaves the EU without a deal, the two will inevitably drift further apart

As we wait for the political machinations of the UK’s imminent exit from the EU to come to some kind of conclusion, the probability of leaving without a deal grows. This will cause significant headaches all around, but the feeling in industry now is that it’s survivable, given time and support.

Even if some form of withdrawal deal is agreed, that doesn’t mean things will stay the same as they are now. There will inevitably be new processes and institutions, acting in parallel within the EU and the UK.

At least, they’ll start off parallel, but inevitably there will be some divergence. Particularly when it comes to regulatory decisions. Even if the legal frameworks are directly transposed, there is always room for differences of interpretation. At a February meeting on policy priorities for UK chemicals regulation post-Brexit – held by the Westminster Energy, Environment and Transport Forum – Dave Bench, director of EU exit at the UK’s Health and Safety Executive, captured it well: ‘Having the same framework doesn’t mean that there won’t be different decisions, even within the current frameworks.’ Already, within the EU, member states can make their own decisions about products that the EU has approved centrally, and apply tighter criteria. ‘The way we operate now, we don’t always think the same – our conclusions aren’t always the same on the basis of the same dossier. Some of these dossiers are enormously complex, it’s almost unimaginable that two sets of very competent experts would come to the same conclusion,’ Bench continued.

That presents both challenges and opportunities. There is a desire to maintain as close an alignment between the EU and UK as possible, so as to keep trade as frictionless as possible. This is particularly acute for chemicals, as components and ingredients can cross borders multiple times during the course of manufacturing a finished, formulated product. That means making sure all those ingredients and components are approved in both markets.

But equally, there is an opportunity for the UK to take its own line on issues where, perhaps, decisions have become more politicised and less reliant on scientific evidence. That might include agricultural biotechnology and genetically modified crops, and the various new families of advanced medical treatments such as stem cell and gene therapies, RNA interference or even gene editing.

That’s not to say the UK should have more lax or business-friendly regulations. If anything we should look to increase standards of health and environmental protection – guided by the best scientific evidence. But there is scope to make the process more streamlined when it only has to apply to the UK and not the diversity of the entire EU bloc.

No comments yet