Neil Withers reflects on the 2019 Nobel prize in chemistry, awarded for developing lithium-ion batteries

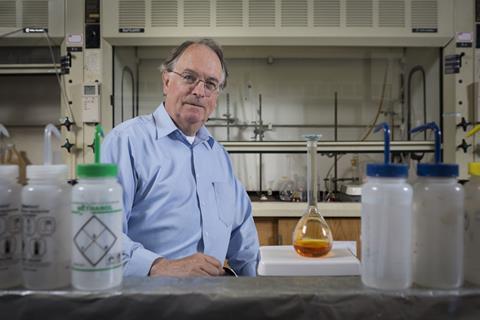

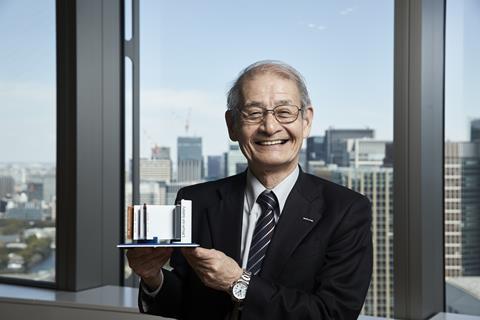

By the time you read this, I’m sure you’ll be aware that John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino have been awarded this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry ‘for the development of lithium-ion batteries’. ‘And about time too’, seems to sum up most of the reaction to the announcement.

For the full story of how we all came to be carrying lithium around in our pockets and purses, you can read our news story and explainer article. But briefly, Whittingham spotted the potential for lithium, the lightest metal element, to be an energy carrier in batteries while he was working at Exxon in the US during the oil crisis of the mid-1970s. Although the principle was sound, the materials used weren’t perfect. Goodenough, then at Oxford University in the UK, used his unrivalled knowledge of metal oxides to come up with the LixCoO2 cathode. Yoshino next added the graphitic anode. Batteries with basically this set-up began to emerge in consumer devices from the early 1990s and are now ubiquitous.

These are pretty old discoveries – 30–45 years old depending on how you count it – so why has taken so long to be recognised by the Nobel committee? Well, you’ll have to ask them – or more realistically wait 50 years until the nominations and discussions are publicly released.

Personally, I’ve been rooting for at least Goodenough to get the call from Stockholm since 2008. As a former solid-state chemist myself, I first became aware of his work during my PhD. I was making – or more often trying to make – compounds with interesting magnetic properties. Characterising these low-temperature structures using neutron and x-ray diffraction data was… challenging. And looming over my work were the Goodenough rules, which he experimentally determined in the 1950s. One of the very last steps of my career as a researcher was wrestling with these rules, as expounded in his book Magnetism and the Chemical Bond, while doing the final corrections to my PhD thesis. I remember complaining to my supervisor how hard it was to get my head round them, and being not-so-gently reminded that PhDs typically demand a degree of intellectual effort!

I’ve hardly been alone in tipping lithium-ion batteries for the prize year after year. The overwhelmingly positive response to this year’s award showed just how many people have been eagerly anticipating this announcement. The prize ticks several boxes that we always hope the Nobels will achieve: the topic is hugely relevant to the general public, as nearly everyone now owns a lithium-powered device or three; both Whittingham and Yoshino performed some of their prize-winning work in industry, where the great majority of practising scientists are found; and finally, in this International Year of the Periodic Table, it’s great to see a single element being, in a way, recognised. How many people will have seen the name of element number three in the news in recent days?

And that is the great and enduring power of the Nobel prizes: it guarantees chemistry (and the other disciplines on their days) some broadly positive headlines in the world’s media for one day a year. Sadly, that does not eclipse the persistent problems with the prizes: their lack of acknowledgement for teamwork and collaboration and their lack of diversity. The latter all too clear this year, with nine out of nine science laureates being men.

It’s clearly possible to hold both these notions in mind at once – we can celebrate Goodenough, Whittingham and Yoshino’s achievements while also feeling unease about what message the nature of this year’s science laureates sends to half the world’s population. So this year, let’s celebrate – and hope that the Nobel committee’s recent call for more diverse nominations pays off in future years.

No comments yet