Claims of an AI revolution in drug discovery are missing the biggest problem

I feel safe in predicting a continued barrage of stories about extraordinary advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, with plenty of claims about their revolutionary implications. I should note immediately that I’m not advocating for a blanket dismissal of all of them, because you never know: some of these things might indeed prove to be great progress. But what I will make the case for is pausing to think about any such claims in their proper context.

That means thinking about them more from the standpoint of a process engineer. You need to look at where the new technology is being applied, and then step back for a larger view that takes in more of the steps before and after it. I can illustrate that with the field that I know the best from my own experience, which is drug discovery.

In drug research we typically don’t actually find out if our best candidates work until the very end stages of the whole research effort: the phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in human patients. And these are by far the most expensive parts! So much of the work that goes into the stages before those trials is designed to test for the failure points that we have a chance of finding before the big money gets spent, but if your candidate makes it through those, it’s time to take a deep breath and to reach deep into your pockets.

From an outside perspective, this is insane. No one would choose to discover drugs this way if they had any reasonable alternatives. And honestly, most of the alternatives probably do sound more reasonable. At the same time, we biopharma types are not idiots (at least not all of us, and not all the time). We conduct research in this way only because we have, as yet, found no better way to do it. We are, believe me, practically panting for such to emerge.

It sounds like someone trying to sell a new car model by pointing out that its windows roll up and down much more quickly

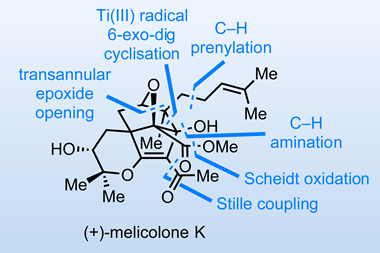

Now, one of the perennial stories about AI in drug discovery is one company or another trumpeting that their new technology can find lead compounds so much more quickly than the old-fashioned way. Phrased carefully, that can indeed sound like a revolution: instead of two years or more (for example) the new Lead-O-Tronic system found this one in four months (or some other exciting unit of time)! But what does that really give you?

Well, it gives you a speedup in the earliest and least expensive part of the whole process, one that is often as not the shortest as well. Unfortunately, that’s not quite the material of a revolution. Compounds found (wholly or partly) by such AI methods are still going to be subject to the same white-knuckle dice-rolling as all the others when they get into human trials, because we have (as yet) no computational tools that really help us predict whether we have picked the right target, the right disease, the right biochemical pathway, or the right compound to affect it without doing anything unexpected along the way. When AI systems start to help with those questions, the revolution may really be at hand. But as it stands, some of the current press releases sound like someone trying to sell a new car model by pointing out that its windows roll up and down much more quickly than the competition. If you read these releases closely, you can often spot a sleight-of-hand moment where the (truly fearsome) costs of drug development are said to be lowered by the new technology, but just how that happens never seems to be spelled out clearly.

So, whenever you hear of some new breakthrough (in any field, not just biopharma) try to run through some key questions. Is the claimed advance really that much faster than the current methods? Is the area that’s being sped up anywhere close to a rate-limiting step or a significant expense in the overall process? How much will things really change in the end? If you don’t have the expertise to judge these in the field under discussion, try to find someone who does (and preferably someone who has no interest in selling you anything). This will put you well ahead of the people who are hunting the headlines, believe me.

No comments yet