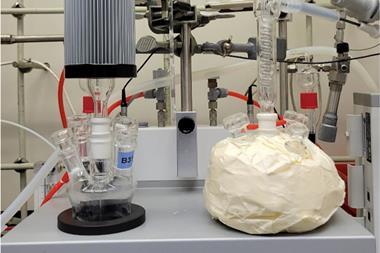

Water, water, everywhere… but in labs most goes down the sink. That’s the sad truth in chemistry where water-cooled condensers – essential for preventing the escape of reaction products during heating – waste huge amounts of this increasingly valuable resource. A single condenser can use over 2 million litres per year. This issue is part of the paradox that afflicts science: while the world looks to it to provide new technologies to cut energy consumption and shepherd scarce resources, labs themselves are resource hungry and produce large volumes of waste.

Labs consume far more water and energy than similar-sized buildings: they account for around 60% of a university’s total water use and as much as 65% of a university’s total energy consumption. All the labs in the world also generate 2% of plastic waste and each chemist produces, on average, 4–15 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year.

Chemists are not blind to this dilemma. A global survey recently found that 84% of chemists want to reduce their lab’s environmental footprint, and many of them are taking action. Chemistry World has recently looked at the first paper that compares different air-cooled condensers. It provides a handy way for chemists to see which solution might work best for them when conducting reactions under reflux. Promisingly, even relatively low-tech and cheap options perform quite well, offering cost-effective ways to save water and money.

Another recent paper, from the lab of Nobel prize winner Ben Feringa, outlines and quantifies the benefits of going green with simple solutions such as closing the sash on fume hoods (reducing air flow by two-thirds and saving on heating), insulating rotary evaporators’ water baths (cutting energy use by 56%) and idling electron microscopes at night (saving 40% of their energy use). This saves the faculty thousands of euros per year.

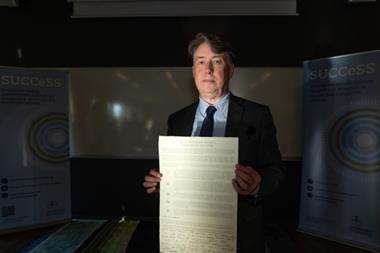

Such work is part of a growing trend of scientists thinking much more about their environmental footprint and ways to shrink it. The Royal Society Of Chemistry’s recent Sustainable Laboratories programme is one of those initiatives, with the first grants released earlier this year to cover small changes that make labs more sustainable.

To make these kinds of changes in labs commonplace what’s needed is education. The authors of the air-cooled condenser paper urge tutors to include such devices in organic chemistry practicals so students are aware of them from the off. Educational programmes of this kind are already being rolled out at many universities. Such simple measures can bed in the concept so that the scientists of the future are already primed to make their labs greener. That way change becomes second nature.

No comments yet