The public health impacts of climate change are growing rapidly, a crisis that has escalated to a global health and food emergency. For example, anthropogenic climate change is responsible for more than a third of the 5 million heat-related deaths reported each year,1 with predictions this could rise by 370% by mid-century if global mean temperature continues to rise to just under 2°C.2

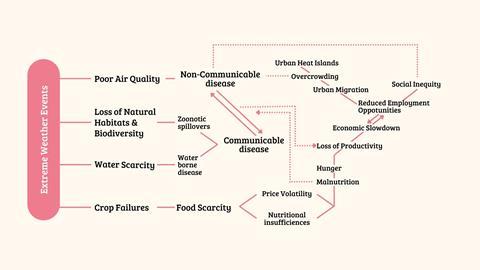

As well as heat-related deaths, extreme climate events such as droughts, floods, dust storms, wildfires and cyclones devastate the systems that are vital for our health and survival.3 Crop failures, reduced livestock productivity, and biodiversity loss have led to food scarcity and rising food prices, increasing the risk of malnutrition.4,5,6 Climate instability also drives infectious disease outbreaks and zoonotic spillovers, compromises water and air quality, which impacts livelihoods, and people’s physical and mental wellbeing.

At the UN COP28, 151 countries endorsed the inclusion of health in climate change negotiations through the Declaration on Climate and Health. However, much of the climate action, particularly in India, is focused on the transition to clean energy, with less attention given to the health hazards posed by the changing climate. India can leverage its existing legal infrastructure to fortify climate action and ensure public welfare.

India must endeavour to position health and wellbeing at the heart of climate action. The breadth of diversity of India’s climate, geography and demography mean that a one-size-fits-all approach, as is the current practice for climate action, is inadequate. India needs hyper-local, contextual climate adaptation strategies to address local challenges, while ensuring coordinated efforts nationwide, paving the way for sustainable development and resilience in the face of climate change.

Scale for Health

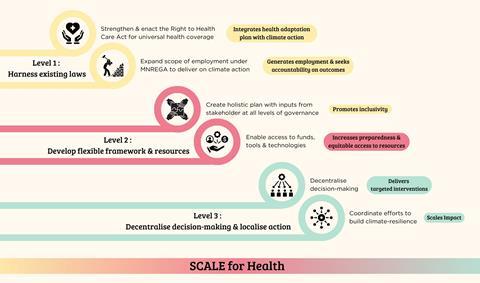

India needs a plan that can deliver hyper-local needs as well as adapt in response to change, such as new policies, exigencies, economic interests or technological advancements. To achieve this, an action scales modelcalled Scale (strategy of climate-change adaption through localised empowerment) for Health is proposed, which while working within the ambit of a broad framework of common goals, can flexibly conceptualise, identify and appraise actions tailored to local contexts, resulting in the collective impactful outcome.

Scale for Health requires three levels of reforms: harnessing existing laws, implementing a flexible framework and decentralised decision making.

Harness the law

India has a strong tradition of using rights-based legislation to enhance public welfare, which offers a ready-made template for prioritising health and well-being in climate discourse. This legislative approach empowers citizens to claim their rights while increasing the accountability of individuals and institutions tasked with respecting, protecting and fulfilling these rights. It encourages people to participate in shaping decisions that impact their rights. It also mandates those responsible for fulfilling rights to acknowledge and understand how to respect these rights and remain accountable.

For example, the Right to Education Act 2009, which offers children aged 6–14 free and compulsory education, significantly increased school enrolment rates. The National Food Security Act 2013 has been instrumental in alleviating hunger.8 Recently, Rajasthan introduced the Right to Health Care Act 2022 to ensure healthcare access. Expanding this Act to include the following provisions offers a promising foundation for a holistic health adaption plan:

- Right to food: The right to be free from hunger and malnutrition, with regular access to affordable, adequate, safe, and nutritious food for a healthy life.

- Right to housing: The right to live in a safe, private space with facilities conducive to a dignified life.

- Right to sanitation: The right to safe excreta disposal facilities, including access to sewerage facilities for wastewater treatment.

- Right to water: The right to access safe, adequate, and affordable drinking water for personal and domestic use.

Expand the rural employment guarantee

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MNREGA) is the largest social protection program in the world, offering up to 100 days of guaranteed work each year to rural Indians to lift them out of poverty.8,9,10 A major drawback of this scheme is that it operates on the principle that employment depends on the ‘supply of work’ (beneficiaries seeking employment) rather than the demand for it (outcomes-driven employment generation).11 By incorporating climate adaptation strategies into the scope of employment offered, a greater ‘demand for work’ can be created locally. This not only creates a sense of ownership among the beneficiaries of the scheme, but would impart essential skills that communities need to adapt to climate change. Furthermore, since MNREGA mandates social audits, accountability and transparency, it enables us to track progress on climate action.

Develop a flexible framework and collate resources

The inclusion of state and local body representatives in developing national climate action plans will bring local insights and ground realities into the planning process, ensuring that strategies are practical and relevant to the regions they serve. It also enables the exchange of ideas and good practice and identifies a pool of resources that can be shared. This collaborative approach fosters a sense of ownership among different levels of government and encourages them to actively participate in implementing and monitoring strategies. It also facilitates better coordination between central, state and local authorities, resulting in streamlined communication and a more unified response.

Decentralised decision-making

India’s laws, though comprehensive, often fail at the implementation stage. Overcoming this challenge lies in empowering local governance bodies. By providing the autonomy to tailor their responses according to local conditions, resources can be allocated more judiciously, and targeted interventions can be implemented effectively. This approach enables local bodies to leverage their unique strengths, understand their specific challenges, and engage citizen participation leading to more effective outcomes.

Ideally, the devolution of power should be at the District Magistrate (DM) level, in close coordination with panchayats (self-governing bodies at the village level) in rural areas. A district-level task force team under the authority of the DM comprising officials from several line departments responsible for infrastructure and utilities like water supply, drainage, pollution control, health and so on would be in-charge of situation monitoring, executing state directives and coordinating efforts with and between state-level authorities and the panchayats.12,13

Lessons from Covid-19

The initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic in India highlighted centralised tendencies, exposing weaknesses in administrative and planning processes for a country this large. The experiences from the Indian states of Kerala, Rajasthan, and Odisha demonstrated that a decentralized response was more beneficial, highlighting the pivotal role local governance plays in harnessing the commitment of individuals towards urgent public needs. The experience of coordinating responses to Covid-19 led to new forms of cross-sectoral and multi-scalar collaborations, enhancing flexibility and responsiveness at the local level. These emergent forms of collaboration across established institutional divides have the potential to create lasting changes in local behaviour and practices, paving the way for more effective governance and crisis management in the future.

Structured framework for implementation

The successful rollout of Scale for Health requires a robust bi-directional flow of responsibility (as summarised in Table 1) and accountability between three key actors: central government, state government(s), and district governance bodies for a structured assessment of the effectiveness in delivering responsive, community-centered climate action (as detailed in Table 2).

Table 1: Proposed responsibilities across governance levels

| Component | Central government | State government | District level |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Policy and legislation |

Set overarching objectives and framework |

Facilitate resource and funds distribution based on population size |

Design and execute tailored adaptations |

|

Resource pooling |

Manage National Resource Pool with funds and instrumentation for states |

Establish State Resource Hubs to distribute resources to districts based on localized needs |

Access pooled resources; district magistrates allocate resources locally |

|

Decision-making |

Provide broad guidelines and performance incentives for states |

Support and manage inter-district coordination |

District Magistrate-led task force decides allocation of resources and funds |

|

Implementation |

Fund adaptation programs that align with framework established |

Coordinate regional capacity building, training and awareness aligned with state goals |

Engage local panchayats and communities, facilitating bottom-up feedback for policy improvement |

|

Monitoring and reporting |

Maintain a national-level digital platform for real-time monitoring of impact |

Monitor and report district-wise performance, share feedback with centre and district |

Provide real-time progress to state, and reassess policy prioritization based on feedback |

Table 2: Impact metrics and evaluation

| Strategic KPIs | Success Metric | Definition and Target | Measured by |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Health hazard reduction |

Reduction in climate-related health incidents |

Reduction in reported heat stroke cases, vector-borne disease outbreaks, and respiratory issues. Target: 25% decrease within five years |

Monthly district health data |

|

Resource optimization |

Efficient distribution and utilisation of resources |

Increased rate of resources delivered within expected timeframes; fewer cases of resource duplication. Target: 90% on-time distribution |

Annual national progress report |

|

Community resilience building |

Citizen participation in climate awareness and resilience programs |

Increase in community members trained in climate resilience practices. Target: 50% of local households engaged annually |

Local surveys and participation records via panchayats |

|

Policy effectiveness |

Adaptation rate of central policies to local needs |

Percentage of national policies adopted and successfully implemented at the district level. Target: 80% or higher |

Annual national progress report |

|

Local budget utilisation |

Utilisation rate of district-allocated climate resilience budget |

Proportion of district funds utilized in climate adaptation projects. Target: 85% of funds utilised |

District-wise financial audits and annual national progress report |

|

Operational KPIs |

|||

|

Real-time data reporting |

Data accuracy and frequency |

Timeliness and accuracy of district data fed into into national digital platform Target: 95% data accuracy and daily reporting frequency |

Availability of real-time data on national digital platform |

|

District-level decision efficiency |

Decision-making and response time |

Average time taken for district task force to respond to emerging climate risks. Target: Response within 48 hours |

District-level decision log |

|

Resource allocation speed |

Resource allocation turnaround time |

Speed at which resources reach affected districts from state and central pools. Target: 72-hour resource allocation window |

District-level tracking of resource dispatch and arrival |

|

Collaboration and coordination |

Inter-agency and inter-district collaboration frequency and quality |

Number of joint programs, and best practice sharing sessions between districts. Target: 10 collaborations per year per district |

Annual national progress report |

|

Public satisfaction with local governance |

Community feedback and satisfaction |

Community approval rating of district-led climate initiatives. Target: 70% positive feedback |

Annual community satisfaction survey |

Scale for Health revolutionises the traditional dynamics between central and state governments by incorporating a district-level governance dimension and demanding greater bi-directional flow of responsibility at all three levels of governance. This collaborative approach aims to address the bureaucratic complexities that often arise within India. However, confusion regarding roles, responsibilities and information flow may initially lead to inefficiencies or delays. Additionally, political alignment between central and state governments might influence the equitable distribution of resources and funding, potentially resulting in uneven outcomes and dissatisfaction among different states.

However, in the long term, Scale for Health fosters a natural interdependence and encourages a proactive feedback mechanism among key stakeholders. This approach promotes a positive work culture that values flexibility, accountability, and results-driven efforts. By adopting a participatory model for decision-making and implementation, it ensures need-based interventions. Most importantly, this strategy effectively integrates the resolution of pressing global challenges with diverse public welfare activities, respecting regional diversities and aspirations.

References

1 A M Vicedo-Cabrera et al., Nat. Clim. Change, 2021, 11, 492 (DOI: 10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x)

2 M Romanello et al., Lancet, 2023, 402, 2346 (DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01859-7)

3 K L Ebi et al., Annu, Rev. Public Health, 2021, 42, 293 (DOI: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-012420-105026)

4 T Hasegawa, Sci. Data, 2022, 9, 58 (DOI: 10.1038/s41597-022-01150-7)

5 S Mishra et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2023, 24, 15670 (DOI: 10.3390/ijms242115670)

6 P Ray et al., Sci. Total Environ., 2022, 849, 157850 (DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157850)

7 J Kaur, Webology, 2021, 18, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4080553

8 S Turangi, South Asia Research, 2022, 42, DOI: 10.1177/02627280221085195

9 R Breitkreuz, Dev. Policy Rev., 2017, 35, 397 (DOI: 10.1111/dpr.12220)

10 S Patwardhan and L Tasciotti, J. Dev. Effectiveness, 2023, 15, 353 (DOI: 10.1080/19439342.2022.2103169 )

11 A A Reddy, SAGE Open, 2021, 11, DOI: 10.1177/21582440211052281

12 A Shringare and S Fernandes, State and Local Government Review, 2020, 52, 195 (DOI: 10.1177/0160323X20984524)

13 A Dutta and H W Fischer, World Dev., 2021, 138, 105234 (DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105234)

Chemistry will support India’s sustainability ambitions

Chemistry is central to addressing challenges across a range of sectors

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Tackling India’s climate change health problems at Scale

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet