Asma Sheikh talks about growing up, discovering her passion for chemistry and being a teaching assistant

I was born profoundly Deaf to Deaf parents who moved from Pakistan to America before my birth. My sister is also Deaf. As a family we all speak Pakistani Sign Language, which I am fluent in as well as American Sign Language (ASL).

Growing up attending a Deaf school in Massachusetts I had no interest in science until middle school. There, a Deaf science teacher taught me in sign language. Chemistry was very visual, and that’s when it became clear that I was passionate about science. Later, at a mainstream high school with hearing peers, there were more opportunities to dive into chemistry, including organic chemistry, which for me was fascinating and intuitive.

Enrolling at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) as an undergraduate, I originally intended to become a doctor or work in the medical field. Organic chemistry was a prerequisite for a premed major. It was a very tough course, taught by Christina Goudreau Collison, but I had a knack for it.

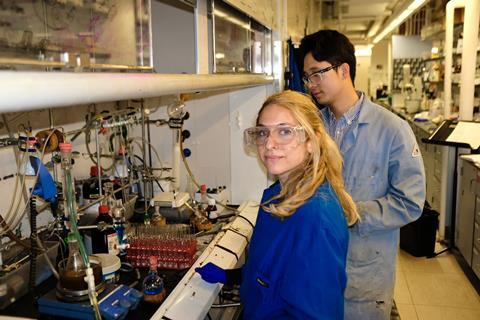

After graduating from RIT with a bachelor’s degree in biomedical sciences, I spent two years as a research assistant at Harvard Medical School. Now I am in my third year of an organic chemistry PhD programme at New York University (NYU), focused on organic synthesis and methodology development.

A new, universal lexicon for organic chemistry

In the hearing community, a common misconception is that sign language is universal. ASL is used here in the US, but different countries have their own sign languages.

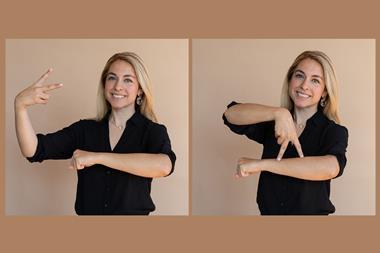

At RIT, I was involved in a project, led by Professor Goudreau Collison, to create new signs for chemistry terms and reactions. It started because several students in our course had various degrees of deafness, and the professor spent a good deal of time fingerspelling.

The signs we developed are very visual. And they can be understood across different sign languages because they depict how the chemistry is happening and what’s going on with the molecules. They replace spelling out reactions, which gets onerous, while also enabling people who speak different languages to communicate and understand chemistry.

I am the only Deaf teaching assistant in NYU’s chemistry department

Working with other Deaf students at RIT to express chemistry concepts in sign language also helped us to learn the subject much better, and we all received top scores compared to the hearing students in the class. The professor noticed that, and she came up to us to talk about it.

Together, we realised that this was a great opportunity, and the project just grew from there. The hearing students in our class also started using their hands to describe and understand chemistry terms and reactions. They found the signs were more useful than what they were hearing in lectures and what they were reading in the textbook, encapsulating everything they needed to know, and so they absorbed the material better.

Teaching the interpreters

I’m very happy at NYU, and operate at the same level as my hearing peers. There is no difference except that I can’t hear and I use interpreters. I can access everything I need at NYU, and my colleagues treat me equally.

My biggest challenge is finding qualified interpreters who can understand and communicate complex organic chemistry. Sometimes I need to teach my interpreters – a responsibility my hearing counterparts don’t face.

After earning my doctorate, I want to continue in the field of research, and maybe do some teaching.

Last semester I taught 16 students – all of whom are hearing – in an undergraduate organic chemistry lab, using an interpreter.

I am the only Deaf teaching assistant in NYU’s chemistry department. A lot of people remark that my interpreters seem to know chemistry and ask if they help me with the material. That’s frustrating. I explain that I’m the expert and my interpreters are just translating from spoken English to ASL.

The signs I was involved in developing at RIT help me to train my interpreters in chemistry. They are a great resource for them to study chemistry and learn how to communicate on their own.

Using an interpreter to teach labs requires a lot of trust because you don’t hear exactly what is being said. So, I usually ask the students to repeat back to me what I have just said.

Every week, I would prepare the interpreters before each lab, assembling a handout on the lab procedures for the day. The interpreters would also review the signs for specific reactions that will be taught and demonstrated.

Deaf people get a lot of pity from the hearing world, but we’re fine and not broken. In fact, the things that we do to adapt can also be applicable to hearing people.

Breaking and connecting bonds and transforming reactants to form products are very visual activities. We could imagine the molecules easily in our mind’s eye, and the way they are transformed reminds us of different hand movements in ASL. This learning method can also be useful for anyone who is not Deaf, and it can help them learn chemistry.

As told to Rebecca Trager

The new signs bringing greater understanding to organic chemistry

Rebecca Trager speaks to a US team developing a sign language lexicon for chemistry concepts that combines form with meaning to make the field more accessible for everyone

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Thriving as a Deaf chemistry PhD student

No comments yet