The UK has a new government. After 14 years of Conservative-led administrations the Labour party secured a huge majority on 4 July, winning 412 of 650 seats.

The result has been broadly welcomed by the science community, although the election campaign itself (in common with the many others taking place around the world this year) focused on immigration, inflation, taxation, cost of living and social inequality. So while science has never been a prominent feature of election manifestos, the most recent crop in the UK made for very light reading indeed and it’s hard to tell exactly what a Labour executive will mean for science. But what is clear is that the challenges it faces are formidable.

Prime minister Keir Starmer’s focus on stability means he has opted to avoid any of the big shakeups that often accompany a change of Downing Street’s residents. The members of his new cabinet have all been appointed to the roles they shadowed in opposition, which means science secretary remains a cabinet-level post, now held by Peter Kyle. UK researchers will surely welcome a less combative relationship with that secretary of state than was the case with Kyle’s predecessor, Michele Donelan, and Kyle has already expressed his own desire for a reset.

The theme of stability extends to Labour’s manifesto pledge for 10-year budgets for the UK’s R&D institutions, including its umbrella funding body UKRI. Scientists have responded positively, though experts point out this is at best an aspiration as it cannot bind future governments. Nevertheless, it at least acknowledges the importance of longer-term thinking and more closely reflects the realities of R&D timescales. Other Labour pledges to boost financial support for start-ups and deliver a leaner regulatory landscape have also been welcomed.

Science exists within a social and political context that cannot be ignored

In the immediate future, however, there are urgent issues to address. University finances are stretched, with tuition fees frozen since 2017 and declining numbers of international students. Chemistry is no exception here, facing falling student numbers at undergraduate level since 2018. At school level, recruitment of teachers continues to fall well below targets and those in the profession feel overworked and undervalued.

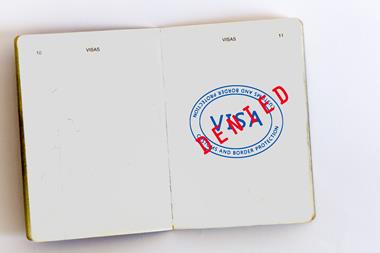

The fallout from Brexit is still being felt too, with the UK in desperate need of a regulatory framework for chemicals – the Royal Society of Chemistry recently called for a national chemicals agency to oversee this work. And while the long-running uncertainty around the UK’s participation in Horizon Europe was finally resolved last year, the UK must still address the problem of attracting international talent. The UK’s withdrawal from the Erasmus scheme, increasing restrictions on movement and the high cost of visas are hampering the UK’s research community.

Arguably the greatest challenge for science and society is climate change and the transition to net zero emissions that is needed to mitigate its worst effects. Unfortunately, the debate on net zero has become politicised and poisonous in recent months. Detoxifying that discussion is vital.

Starmer’s decision to appoint Patrick Vallance as a minister for science suggests that he takes these issues seriously. As a former head of R&D at GSK and then the government’s chief scientific adviser, Vallance has a deep understanding of the complexities of both research and policy. Vallance has backed Labour’s plans for a national energy company and was critical of the previous government’s decision to water down and walk back its net zero commitments.

Straitened finances threaten the local and civic work of universities

There are warning signs for science, however. Vallance has already come under fire from sections of the UK national press for his stance on lockdowns during the pandemic and those attacks were revived after the news of his ministerial role. This partisanship is evident elsewhere with Donelan seeming to drag science into culture war issues or with net zero becoming such a politicised and divisive issue. Scientists might wish to ignore or rise above such politics, but science exists within a social and political context that cannot be ignored.

One of the reasons scientists continue to maintain high levels of public trust is that their work improves people’s lives. And by engaging with the public and serving their communities, they nurture that trust. Yet, as a recent collection of essays published by the higher education charity the UPP Foundation warned, straitened finances threaten this third pillar of university purpose as institutions choose to cut their local and civic work in favour of income-generating education and research.

The new government seems unlikely to fix university finances in the short term. It is committed to raising the R&D budget to £20 billion per year, but this is much less ambitious than Labour’s 2019 promise to invest 3% of GDP within 10 years. Yet commentators have also noted that Labour’s focus on tackling social inequality means it will be looking closely at where in the country research funding goes, and it could push universities to keep up their local and civic activity as a means of tackling inequality. A magic money tree will not be fruiting for science any time soon, but it could still be good news for science if a renewed emphasis on public service and local action helps to bolster the public’s trust.

The UK has a new government. After 14 years of Conservative-led administrations the Labour party secured a huge majority on 4 July, winning 412 of 650 seats.

The result has been broadly welcomed by the UK’s science community, although the election campaign itself focused on immigration, inflation, taxation and cost of living. So while science has never been a prominent feature of election manifestos, the most recent crop in the UK made for very light reading indeed and it’s hard to tell exactly what a Labour executive will mean for science. But what is clear is that the challenges it faces are formidable.

Prime minister Keir Starmer’s focus on stability means he has opted to avoid any of the big shakeups that often accompany a change of Downing Street’s residents. The members of his new cabinet have all been appointed to the roles they shadowed in opposition, which means science secretary remains a cabinet-level post, now held by Peter Kyle.

The theme of stability extends to Labour’s manifesto pledge for 10-year budgets for the UK’s R&D institutions, including its umbrella funding body UKRI. Scientists have responded positively, though experts point out this is at best an aspiration as it cannot bind future governments. Nevertheless, it at least acknowledges the importance of longer-term thinking and more closely reflects the realities of R&D timescales. Other Labour pledges to boost financial support for start-ups and deliver a leaner regulatory landscape were also welcomed.

In the immediate future, however, there are urgent issues to address. University finances are stretched, with tuition fees frozen since 2017 and declining numbers of international students. Chemistry is no exception here, facing falling student numbers at undergraduate level since 2018. The fallout from Brexit is still being felt too, with the UK in desperate need of a regulatory framework for chemicals – the Royal Society of Chemistry recently called for a national chemicals agency to oversee this work. And while the long-running uncertainty around the UK’s participation in Horizon Europe was finally resolved last year, the UK must still address the problem of attracting international talent – its withdrawal from the Erasmus scheme, increasing restrictions on movement and the high cost of visas are hampering the UK’s research community.

Arguably the greatest challenge for science and society is climate change and the transition to net zero emissions that is needed to mitigate its worst effects. Unfortunately, net zero has become a politicised and poisonous issue in recent months. Detoxifying that discussion is vital.

Starmer’s decision to appoint Patrick Vallance as a minister for science suggests that he takes these issues seriously. As a former head of R&D at GSK and then the government’s chief scientific adviser, Vallance has a deep understanding of the complexities of both research and policy. Vallance has backed Labour’s plans for a national energy company and was critical of the previous government’s decision to water down and walk back its net zero commitments.

There are warning signs for science, however. Vallance came under fire from sections of the UK national press for his stance on lockdowns during the pandemic and those attacks were revived after the news of his ministerial role. This partisanship is evident elsewhere with former science secretary Michelle Donelan seeming to drag science into culture war issues or with net zero becoming such a divisive issue. Scientists might wish to ignore or rise above such politics, but science exists within a social and political context that cannot be ignored.

Scientists still enjoy high levels of public trust despite changing landscape because their work improves people’s lives. And by engaging with the public and serving their communities, they nurture that trust. Yet, as a recent collection of essays published by higher education charity the UPP Foundation warned, straitened finances could threaten this pillar of university purpose as institutions choose to focus on income-generating education and research.

It seems unlikely that the government will fix university finances in the short term. It is committed to raising the R&D budget to £20 billion per year, but this is much less ambitious than Labour’s 2019 promise to invest 3% of GDP within 10 years. Yet commentators have also noted that Labour’s focus on tackling social inequality means it will be looking closely at where in the country research funding goes, and it could push universities to keep up their local and civic activity to help tackle inequality. A magic money tree will not be fruiting for science any time soon, but it could still be good news for science if a renewed emphasis on service helps to bolster the public’s trust.

No comments yet