Chemical innovations could lead to new avenues of patent protection

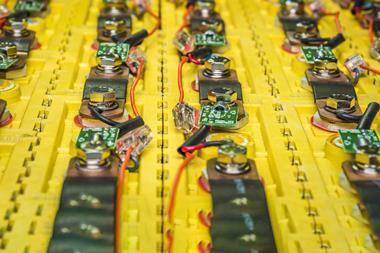

The fundamental chemistry of the lithium-ion batteries that drive our smart phones has remained largely unchanged for decades, but there will come a point where it is no longer sufficient for our needs. We’ve all experienced the frustration caused when our phone dies mid-call or while downloading an important file. There have also been concerns about the safety of our phone batteries which, in some instances, have led to the mass recall of products.

Unsurprisingly, many companies are investigating ways to give our smartphone batteries a boost, with research underway to both improve current technology and find alternatives. For instance, lithium–sulfur batteries are being investigated for long range electric vehicles and lithium–air batteries are being developed for power grid applications. In order for such technologies to make it into our pockets, companies will look to protect these advances – but this is problematic for several reasons.

Battery limits

Lithium-ion batteries have been around since the 1970s and so intellectual property (IP) protection for improvements tends to be narrow. Accordingly, it can be difficult for innovators to get products to market as they may lack the IP necessary to protect their innovations. While new battery chemistries may offer broader protection, identifying alternative battery chemistries is costly and challenging, for instance because of the need to meet safety standards and to be suitable for retrofitting to existing devices.

To date, most of the improvements to batteries have been achieved by refining the architecture and programming of our devices. Greater manufacturing fidelity and improved battery management systems have resulted in big improvements in efficiency, extending our battery life. Of course, it is possible next generation batteries may not be found in the near future simply because the technological challenges are too great. For this reason, innovators may need to consider other ways to secure commercial exclusivity in a sector that has been using the same core technology for so many years.

New approaches

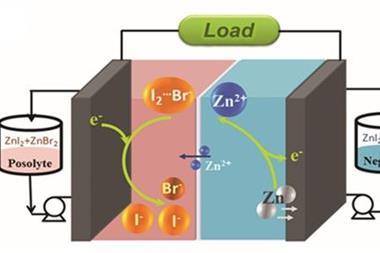

One route to broad commercial protection for a new smartphone battery would be to import existing battery chemistry from another technical field. This is difficult to achieve, but has an advantage as the need to develop entirely new chemical processes is removed. The adoption of existing technology from related fields can attract surprisingly broad IP protection, which in turn improves the likelihood that such technologies will be funded and succeed.

Some innovators may also take a broader view of the battery market place and supply chain to see if they can obtain the monopoly necessary to sustain a new product. They could protect the way in which it interfaces with a device; the essential components and raw materials used to make the battery; or even the process used to make essential components or raw materials.

If a key bottleneck in the supply chain can be found, broad protection for these inventions may be available – which would indirectly protect a substantial portion of the battery market. For example, a patent for an improved lithium extraction process could be used to control the production of batteries for portable devices perhaps even more effectively than patents covering the batteries themselves.

Other strategies companies will consider for obtaining an effective monopoly involve filing IP in spaces which have strict regulations on form and function. If a company is the first to adapt an existing battery process for a device, or the first to implement a new safety feature which may become industry standard, competitors may be forced to use their technology and pay licence fees.

To succeed in claiming a stake in the future of battery technology, manufacturers will consider all of these options, balancing the need to bring new inventions to market quickly with the need to ensure they are patent protected and the scope of that protection relates to the broadest possible range of market applications. This could mean we will see a step change in the sector’s approach to patents in the coming years.

No comments yet