Ben Valsler

This week, Mike Freemantle on the poetic and practical properties of amber.

Michael Freemantle

The English poet and playwright William Shakespeare seems to have been fond of amber. In his comedy The Taming of the Shrew, for example, the fortune seeker Petruchio asks his wife Kate, who has a wealthy father and is the hot-tempered shrew of the play’s title:

‘Will we return unto thy father’s house, and revel it as bravely as the best?

With amber bracelets, beads and all this knavery. To deck thy body with his ruffling treasure.’

Revel bravely with amber? Well, why not? It is an intriguing and beautiful material with a rich history and a variety of uses, not least in jewellery. And as amber is organic, unlike most gemstones, it has some unique properties. For example, I can’t think of any precious product other than amber that increases in value when it has an insect entombed in it.

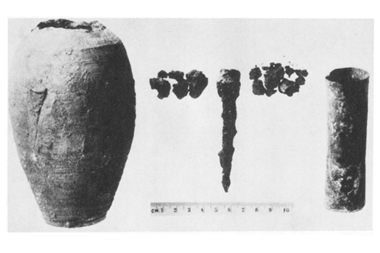

Amber is a yellow transparent and translucent material that is often tinted gold, orange or red and sometimes clouded by tiny air bubbles. It is a fossilised material formed from the soft sticky resin that certain species of trees exude to heal wounds, fight disease and repel fungi and marauding insects. On exposure to air and light, some of the resins slowly harden into solids that can resist physical decay and consequently are able to survive almost indefinitely in soils and sediments.

Since ambers are organic, their age can be determined by carbon-14 dating, but only if they are less than the radioisotope’s limit of about 60,000 years. The ages of older ambers can be inferred from the sediments in which they are found. This requires the use of radioisotopes with half-lives much longer than the 5,730 year half-life of carbon-14. These techniques have shown that most ambers were formed 20 to 130 million years ago although some are over 240 million years old.

Amber and other tree resins typically consist of complex mixtures of organic compounds including carboxylic acids, ketones, alcohols, and – most importantly – terpenes and related terpenoid compounds. Some of these components polymerize over time to form long-chained macromolecular compounds. Resins that do not form polymers are usually soft and more susceptible to decay when buried.

Fossilized resins are found throughout the world. In Europe, for instance, much of the amber derives from deposits in countries around the Baltic Sea, most notably Russia. Much of it is used to make jewellery but there have been, and still are, other uses. For example, in the third and fourth centuries BC, the Greek physician Hippocrates administered mixtures of crushed amber and honey to treat failing eyesight. There is also a long history of the use of powdered amber in traditional Chinese medicine to calm nerves, tackle urinary disorders and promote blood circulation.

The organic nature of the fossilized resin makes it relatively easy to carve and work into beads, ornaments and other treasured objects such as chess pieces, candlestick holders and sculptures. The Vikings, who invaded Britain and other European countries in the 8th to 11th centuries, used Baltic amber in pendants, beads, rings and necklaces. They and many other cultures believed amber had magical properties.

Because of its value, other materials such as glass and synthetic plastics have been used to imitate the material for making jewellery. Synthetic plastics have even been used to embody the remains of insects and therefore make the fake material even more valuable.

So how can you tell if a piece of amber is genuine or not without using destructive analytical techniques? Well if the piece contains an insect inclusion it is not too difficult. Insects stuck in tree resins naturally struggle to free themselves and are thus likely to end up contorted into unnatural positions. If, on inspection, the entombed insect appears to be beautifully laid out, then it is likely to be a fake.

One of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, the English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon, wrote eloquently about the wonder of amber and its power to entrap insects. So let’s leave the final words to him. They are taken from his work Sylva Sylvarum or a Natural History in Ten Centuries which was published in the 17th century:

‘We see how flies, and spiders, and the like, get a sepulchre in amber, more durable than the monument and embalming of the body of any king.’

And with that, Bacon just about sums up the attraction of amber.

Ben Valsler

That was Mike Freemantle. Next week, Kat Arney returns with the aromatic indole.

Kat Arney

In high concentrations it’s most easily recognised as the stink of poop or the stench of coal tar. But in lower amounts it’s a contributor to the floral fragrance of jasmine, tuberose and orange blossoms, and is also used as an ingredient in many perfumes for its fresh, sweet and slightly animal odour.

Ben Valsler

Get a big whiff of indole with Kat next time. Until then, get in touch with any suggestions for compounds to consider: email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet