Meera Senthilingam

This week we're getting rid of a pest infestation. And doing the dirty work is Josh Howgego.

Josh Howgego

Several months ago, while I was studying for my PhD, I became obsessed with moths. At the time I was living in quite a shabby, rented house in Bristol, in the UK. My room was tiny, but it had a pretty large wardrobe. It was a huge thing, which was really rather dark, quite musty and in my case stuffed to the brim with my things. Since the room was so small, I literally kept everything I owned in that wardrobe; tennis rackets, books, lecture notes and clothes were jammed into the space and I spent much of my life climbing around in there trying to find any given object that I might need.

One day I noticed that a pair of my jeans was developing a couple of small holes. At first I thought little of it - clothes get old eventually I suppose - but gradually I started noticing more and more items developing frays and splits.

For some months this went on, with more and more inexplicable holes appearing. Suddenly, it hit me: I had a moth problem.

Try as I might, I couldn't find any direct proof of the moths. But the wardrobe was really dark, so it was hard to be sure. My grandmother advised me to fumigate the whole house, but I thought that was probably a tad extreme, so instead I turned to science. I started to read all about silk moths in an effort to see if there wasn't some way in which I could rid myself of these loathsome Lepidoptera.

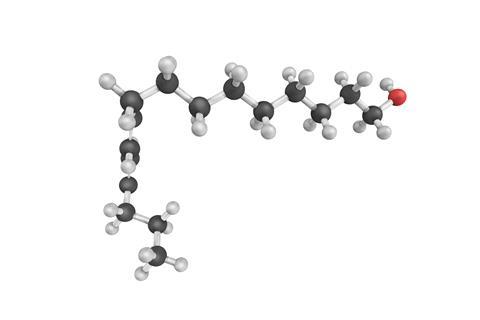

Almost immediately, I was fascinated by the story of Bombykol, the sex pheromone of the female silk moth, otherwise known as (10E,12Z)-hexadecadien-1-ol - a 16 carbon chain with an alcohol group at one end and two carbon-carbon double bonds, one cis and one trans, towards the other end. Being a chemist it wasn't long before I had forgotten any designs I had on getting rid of my moths. Instead I was caught up in the tale of this interesting chemical.

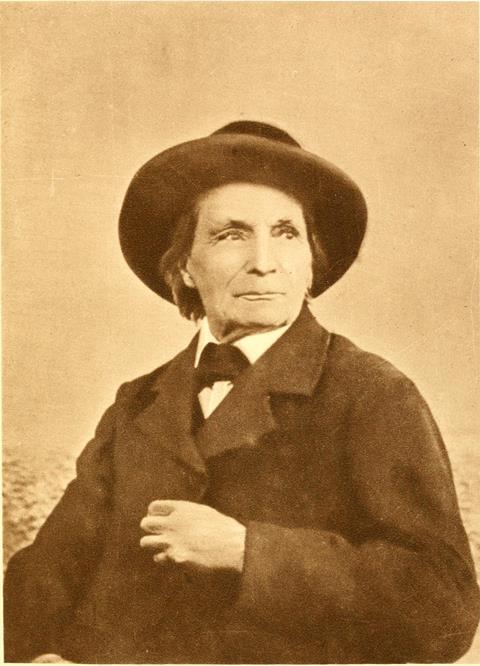

It all started in the 1880s when the Frenchman Jean-Henri Fabre started messing around with silk moths. One key experiment saw Fabre place a female silk moth in a box for a few hours. He then removed her, and left the box overnight. The next morning he found that males were strangely attracted to the empty box, as if some kind of enticing scent had been left for him by the female.

We now know that chemical trail was a pheromone; that is, a chemical secreted by an organism which is then picked up by other members of the same species and elicits a behavioural response.

But it was the German chemist Adolf Butenandt who worked out what was really going on, chemically, with the pheromone that Fabre had described. He started by taking the pheromone glands from the female silk moth and extracting the chemicals produced there into various organic solvents. Since bombykol is only ever produced in tiny quantities by the moths, he needed lots of glands to get even the tiniest amounts of material to work with.

Once he had the crude pheromone mixture, Butenandt purified it by fractional distillation. The problem remained though, how to work out which fraction contained the bombykol? With modern methods like NMR and mass spectrometry this would be the work of a few hours, but Butenandt had none of this. Instead he used the male moths to work out which fractions contained the pheromone, noting that they began flapping their wings like crazy whenever they were exposed to a bombykol-containing fraction.

After lots of cycles of purification, Butenandt had a few milligrams of what he thought was pure bombykol and so he started to try working out the chemical structure of the molecule. He used infrared spectroscopy to work out that there was an alcohol group and two carbon-carbon double bonds present in the molecule. He then used a variety of chemical degradation methods to work out the length of the carbon chain and the position of the double bonds.

In the end Butenandt also managed to confirm the structure by synthesising bombykol from scratch. He prepared all four of the possible geometric isomers of the double bonds, and found that one of them (the right one!) was at least a billion times more effective at exciting the male moths! Finally he had determined the structure.

That's almost the end of the story, but you might be wondering why I started this little tale with an elaborate account of my moth-eaten trousers.

Deterring insect pests is a pretty serious matter. Perhaps not in the case of a scruffy student's wardrobe, but for farmers, keeping insects away from their crops can be a matter of life and death. Pheromones provide a really effective chemical weapon against many insects. Rather than killing pests with poisons which they might become immune to over time, these days famers often make use of pheromones to confuse and divert insects - they go after the pheromones rather than the crops.

So there you have it - bombykol, a sexual elixir for moths, but an illuminating discovery for the rest of us.

Meera Senthilingam

So, using a pest's lustful tendencies to lure them away from valuable crops seems to be quite effective. That was Chemistry World's Josh Howgego with the trapping chemistry of bombykol. Now, next week you may want to hold your nose for this compound.

Brian Clegg

If we are to believe adverts for hair dye, ammonia is something that is best avoided. They often proclaim that a product is 'free from ammonia,' reflecting this simple compound's traditional use in permanent hair colouring to open up hair fibres and enable dyes to lock on to the hair's core. The trouble is that ammonia has an unpleasant, pungent odour that brings tears to the eyes, and has a tendency to burn the skin. It's not surprising that ammonia is being excluded from such uses where possible. But this is not a compound that can be ignored.

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out just ammonia deserves our attention, as well as its uses in industry and nature, join Brian Clegg in next week's Chemistry in its element. Until then, thank you for listening. I'm Meera Senthilingam

No comments yet