Meera Senthilingam

For this week's compound, beware of the silence with Brian Clegg:

Brian Clegg

'The birds - where had they gone? Many people spoke of them, puzzled and disturbed. The feeding stations in the backyards were deserted. The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices.'

That was part of the preface of the first great popular environmental book, Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. Opening with a vision of an imagined town in America, the book describes how the use of a pesticide had, in Carson's words 'already silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America'. This poetic polemic, from an aquatic biologist turned writer, sounded the death knell for widespread use of a compound that had, in fact, saved many human lives - dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, better known as DDT.

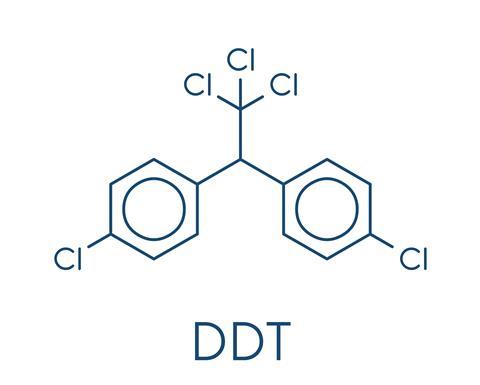

Pure DDT is a relatively simple compound.It is a pair of benzene rings, each with a chlorine attached, joined to an ethane molecule that has three of its hydrogen atoms replaced with chlorine. In practice, the commercial product typically had a number of slight structural differences, but was still primarily DDT.

The compound dates back to the 1870s, first produced by the Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler, but at the time it had no particular use. It wasn't until 1939 that Swiss chemist Paul Hermann M?ller, searching for compounds that would be effective against moths, discovered that DDT was an effective insecticide. M?ller won the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work.

For centuries, a substance called pyrethrum, derived from the dried heads of chrysanthemum flowers, had been used to kill insects. The active chemicals, pyrethrins are powerful insecticides with little effect on mammals, but during and after the war, access to the countries that produced the flowers was restricted and DDT was seen as a very useful alternative. DDT works by increasing the flow of sodium ions through the cell membranes of neurons in insects. By opening up the channels through which these signalling ions flow, the neurons are made to fire artificially. Do this on a large scale and the nervous system is overloaded, sending uncontrolled messages around the body and causing death.

DDT's first great success was to severely reduce the incidence of typhus in Europe by destroying the insects that carried the disease. This success led the World Health Organization to employ it as a weapon in the fight against malaria. This disease is spread by mosquitoes and is a massive killer. WHO figures put malaria deaths in 2010 at around 655,000, though a study in the Lancet in 2012 suggested that a more accurate figure is around 1.6 million, and many of them young children.

Where DDT use was controlled and combined with management of mosquito breeding areas and defensive measures like nets, it was hugely effective against malaria. And with the right worldwide programme, it could have practically wiped out the disease. Unfortunately, in poorer parts of the world it proved impossible to carry out the regime required to be effective. But far more damaging than this was the indiscriminate use of DDT as an agricultural pesticide. This is not only much less efficient than using DDT in buildings and the swamps where mosquitoes breed, but the ubiquitous presence of the insecticide also meant that mosquitoes developed resistance.

Then, just as the World Health Organization was encountering these setbacks, along came Silent Spring. Ironically, Rachel Carson did not advocate banning DDT. She suggested, rather, that its use should be carefully controlled and limited to targeted application where it could do most good - which made a huge amount of sense. But the tenor of the book made Silent Spring a powerful voice for environmental concern. In 1963, the year after the book's publication, US president John F Kennedy set up an investigation specifically to check out validity of Silent Spring's message.

After a lengthy campaign, DDT was banned in the US in 1972, apart from very specific disease control measures, and since then controls have been instigated around the world, although DDT continues to be used in India as an agricultural pesticide.

As to the claims, there is no doubt that DDT does not disperse rapidly. It can remain in soil for many years and tends to build up in animals, particularly in fatty areas of the body as it is highly soluble in fats and oils. And there is considerable (though disputed) evidence of damage to birds, particularly the large predators at the top of the food chain, and to aquatic life. The effects of DDT on humans are less well defined, though it seems likely that high doses can damage the reproductive system.

DDT presents a real dilemma. There is no doubt that used correctly it was effective against malaria-bearing mosquitoes and could have done much more to limit this terrible disease. But equally, the indiscriminate agricultural use was a serious mistake and the environmental impact of DDT should not be underestimated. DDT was not a miracle solution, but we shouldn't forget the estimated 25 million lives it did save and the many more it could have.

Meera Senthilingam

So a hero in terms of human heatlh but a villain to the environment. That was science writer Brian Clegg with the pest-killing chemistry of DDT. Now, next week: we give our immediate environment something nice to smell, as we discover the compound holding the key to a long-lasting perfume.

Josh Howgego

To be smelly, a molecule has to be able to evaporate easily, so that it can waft up and into our noses. The general rule is that the larger a molecule is, the less volatile it is. But if all the perfume evaporated as soon as you sprayed it on, you'd feel a bit short-changed when you arrived at your date, or business meeting, smelling fairly normal. So to get a perfume right, the designers need to perfect the mix between molecules which evaporate quickly (the so-called top notes) and those which linger a little longer (the middle and bottom notes).

Muscone's large size and relatively low volatility make it an excellent bottom note, and it also acts as a fixative, helping to trap some of the other, lighter molecules in the perfume, meaning that you can smell them, too, for longer. The problem with muscone is where to get it from.

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out the ethically questionable natural source of muscone, as well as how chemists are trying to overcome this challenge, join Josh Howgego in next week's Chemistry in it's element. Until then, thank you for listening. I'm Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet