Ben Valsler

This week, Brian Clegg mines the mineral that links the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Girl with the Pearl Earring…

Brian Clegg

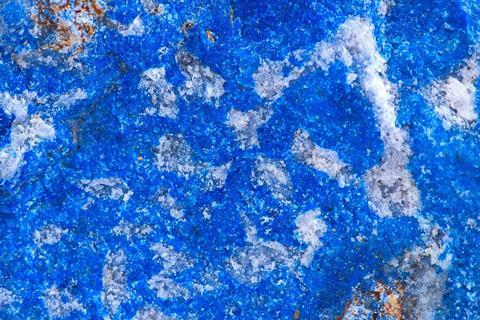

There is surely a special place in any chemist’s heart for compounds that sound as if they’re straight off the pages of a comic book – and lazurite sounds as if it has to be something a supervillain uses to create a world-destroying laser. In reality, though it’s the secret behind many a pharaoh’s blue bling.

Lazurite is fairly complex as minerals go, combining aluminium silicates with sodium, calcium, sulfur, chlorine and sulfates . The result is a rich, brilliant blue colour. This is not to be confused with lazulite, another blue crystal that combines aluminium phosphate with magnesium and iron. Lazulite has its place in the gemstone market (and is a favourite amongst the crystal healing brigade), but lazurite has an altogether more regal role to play. It is the source of the famous ancient pigment and semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli.

Just to make things even more complicated, a second mineral with the odd name hauyne is also considered as lapis lazuli – it has pretty much the same composition as lazurite, but with more sulfate than sulfide, making it translucent where true lazurite is opaque. The lazurite used in the ancient world was in reality primarily hauyne – which was first identified in the nineteenth century in lava of Vesuvius and named after the French mineralogist René Haüy. All lazurite seems to be associated with sources of magma.

Lapis lazuli – the name simply means blue stone – also contains a range of other minerals, giving it paler striations and variations in its blue tint, including calcite (white crystalline calcium carbonate), pyrite (the glittering fool’s gold of iron sulfide) and sodalite (a blue silicate). It’s the sulfur in the crystal that gives it the dramatic blue colour that would make it so treasured: the structure enables an electron to make a jump corresponding to a deep blue wavelength of around 617 nanometres.

The material has been worked for over 6,000 years. Although we now most associate it with ancient Egypt, the neighbouring Mesopotamian civilisations also made wide use of it. In both cases the mineral came from mines in the Kokcha river valley in a mountainous region of Afghanistan, one of the reasons this was a rare and expensive substance. It has since been found in Chile, Myanmar, Russia and Tajikistan. The four-thousand-year-old Sumerian poem the Epic of Gilgamesh – pretty much the oldest known written work and the source of some of the early material in the Bible – refers to lapis lazuli. We read in the translation by N. K. Sanders:

‘I will harness for you a chariot of lapis lazuli and of gold, with wheels of gold and horns of copper.’ And when Gilgamesh kills the bull of heaven, ‘They admired the immensity of the horns. They were plated with lapis lazuli two fingers thick.’ When describing a reward, the epic refers to ‘lapis lazuli, gold and carnelian from the treasury.’ Note that lapis lazuli takes the lead amongst the precious materials.

In Egypt, amulets, ornaments and jewellery were all fashioned from the material – as, allegedly, was Cleopatra’s blue eyeshadow. Since the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the 1920s, the most famous Egyptian example of lapis lazuli work was Tutankhamun’s face mask where it highlights his eyes with inlays, just as it is said to have done for Cleopatra.

Before the introduction of synthetic dyes, painters were extremely limited in the colours available to them. A highly desirable – and the most expensive – pigment was a rich blue powder produced by grinding up lapis lazuli. It was known as ultramarine – literally ‘beyond the sea’ – because the Italian merchants who named it imported it from distant Afghanistan.

The expense of ultramarine meant that it was mostly used for images of high status wearers of the colour blue, notably the robes of the Virgin Mary. It’s said that Michelangelo left his painting The Entombment incomplete because he couldn’t afford the ultramarine to finish it off. Ultramarine also famously colours the head scarf of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. In fact, Vermeer was a huge fan, using ultramarine even where it doesn’t show to give added brightness to whites.

![Jungfrun i bön [The virgin in prayer] (1640-1650). National Gallery, London.](https://d2cbg94ubxgsnp.cloudfront.net/Pictures/480xAny/1/3/4/141134_Sassoferrato_-_Jungfrun_i_bon.jpg)

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the natural substance has been replaced by a synthetic ultramarine, originally discovered as a by-product of lime kilns, which is not only cheaper, but a more vibrant shade of blue that is closer to the colour of the gemstone than the traditional powdered form. Because the mineral can lose sulfur, and hence its intense colouration, probably through interaction with oil binders in the paint, some paintings now suffer from ‘ultramarine sickness’ as the blue fades away.

Lazurite, lapis lazuli and ultramarine may never save lives or be used in a high-tech manufacturing process. But the mineral that was more treasured than gold, adorned the faces of Tutankhamun and Cleopatra and hid the hair of the Girl with the Pearl Earring is a colour that gives us pleasure: and surely that can’t be bad.

Ben Valsler

Brian Clegg with lazurite. Join us next week when Katrina Krämer speaks to Stanford University’s Ross Milton about a class of enzymes that are fundamental to almost all life on Earth, suggested on twitter by @SimonBayly…

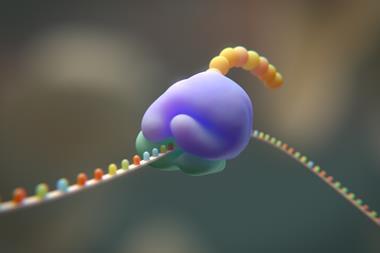

Katrina Krämer

Chemists have been fascinated with nitrogenase’s inner workings for a long time. And still, after almost 100 years of research, they are not quite sure how the enzyme does its nitrogen-fixing magic.

Ben Valsler

Until then, get in touch with any suggestions for compounds to cover – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for listening.

No comments yet