Meera Senthilingham:

This week, cosmetic chemistry with Ben Valsler.

Ben Valsler:

The chemistry of cosmetics is constantly caught in controversy. The esoteric-sounding ingredients listed on make up, shampoo and other personal hygiene products can alienate and worry consumers, some of whom are concerned about the impact of putting ‘synthetic chemicals’ on to their skin. This leads to an ongoing tension in cosmetic marketing between the desire to sound cutting edge and ‘sciencey’ versus the appeal to natural, traditional materials perceived by the public as ‘safe’.

One recent controversy has been around a family of preservatives known as parabens, which are found in cosmetics, shampoos and toothpastes, and also as a food additive, where they act as an antibacterial and antifungal agent, extending the shelf life of products significantly.

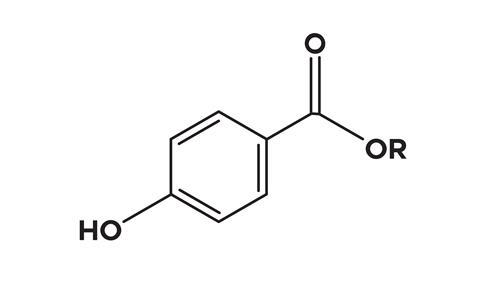

The parabens include methylparaben, ethylparaben, propyl, butyl and heptyparaben, all of which are often represented in lists of ingredients by their E numbers. They’re esters of para-hydroxybenzoic acid, and although they can be found in some fruits, vegetables and other natural sources, all of the parabens we use commercially are produced synthetically.

Cosmetic ingredients are subject to regulation, of course, and this is usually backed by scientific research. But we stumble when potential problems are subtle or may not manifest for some years. How much concern is enough to warrant a ban? Should products be pulled from the shelves at the first publication of a scientific paper that shows a potential link between one of their ingredients and cancer? The role of science in perception of risk, and especially in policy decisions, is far from straightforward, and sometimes plays second fiddle to public perception.

While the scientific jury is still out on health risks of parabens, some researchers are concerned. Initially these preservatives were thought to be non-toxic, rapidly metabolised and ultimately excreted, but a 2004 study by Philippa Darbre published in the Journal of Applied Toxicology found intact parabens in human breast cancer tissue. There’s no indication there that the parabens actually caused the tumours, but it did show our understanding of their metabolism may have been mistaken.

Another concern (and in part the inspiration for Darbre’s research) arises from their ability to mimic the natural hormone oestrogen. If you’ve been following the ongoing discussion around Bisphenol A, another compound where public perception of risk seems to be shaping policy, then the concept will be familiar – hormone mimics may be altering physiology in subtle ways, and people have hypothesised links to early onset puberty, increase in cancers and even, when these mimics enter the waste water system, feminisation of fish in the wild. These sorts of issues take us away from traditional discussions of toxicity – a compound might not directly kill or injure cells, but could cause creeping differences over generations.

Public pressure combined with commercial interests has led to a raft of ‘paraben-free’ products

These studies, and the concerns that they cause, leak into public consciousness through email campaigns and through news stories on special-interest websites. I’m sure you will have seen comments on social media warning you away from certain products, decrying their ‘toxic’ effects. This tends to be most prevalent when the products involved are for use on, or marketed to, children, which adds extra tension to the heart strings. These social media scares often present the evidence as black and white, ignoring the sorts of things someone with a science background would look for – the size of the study, whether the effects are dose-dependent, reproducibility and so on. With parabens, one study found that even in the strongest cases, the oestrogenic effects of parabens may be as much as 10,000 times weaker than the real thing, but did call for further research to understand whether such low activity could still be significant.

Public pressure combined with commercial interests has led to a raft of ‘paraben-free’ products hitting the market in recent years. These aren’t niche products – you may have seen them in your local supermarket or seen the paraben-free logo, of which there are many, gracing the shelves of the big pharmacy chains. The driver may be partly financial – parabens are cheap, and public demand may mean you can sell paraben-free alternatives as premium products. Other companies are willing to stick their heads above the paraben parapet. On the website of one high street cosmetics manufacturer you can find a defence of paraben use, saying that when it comes to ingredients that prevent microbial growth, ‘the parabens are still the safest and mildest we can find.’

Regulation has eventually caught up with public concerns. In 2014, the European commission banned the use of five parabens, owing to the ‘lack of data necessary for reassessment’. Shortly afterwards, the commission dramatically reduced the permitted maximum concentration of propylparaben and butylparaben, from the currently allowed limit of 0.4% to just 0.14%. Further restrictions were placed on products designed for ‘the nappy area’ of young children, where skin damage may increase skin penetration.

Exclusion of parabens can decrease the shelf life and/or increase the cost of common cosmetics, but the moral of the paraben parable is that science is not always at the centre of decisions about safety.

Meera Senthilingham:

Chemistry World’s Ben Valsler there with the many faces of paraben. Now, next week from cosmetics to medicines…

Brian Clegg:

I first came across it as many others will have in a cream as a treatment for exzema and dermatitis. This reflects the compound’s immunosuppressive function, reducing inflammation. But this is only the start of cortisol’s medical role.

Meera Senthilingham:

Find out these other roles in next week’s Chemistry in its element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthlingam.

No comments yet