Ben Valsler

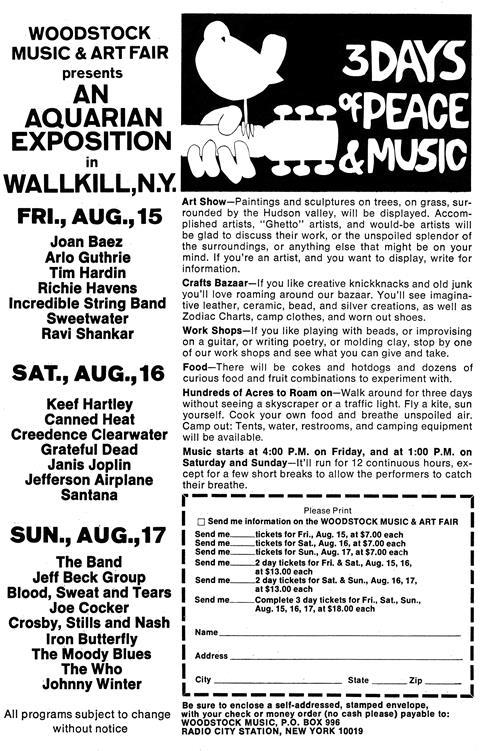

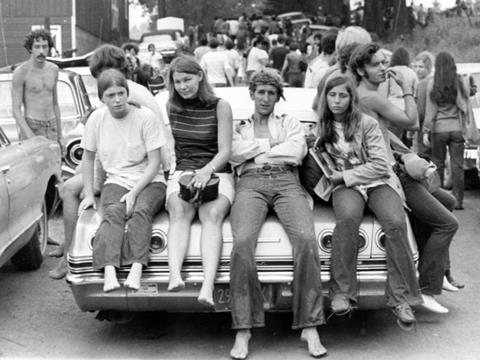

Next year marks half a century since Woodstock, widely regarded as a pivotal moment in pop music history. Music festivals have changed a lot over the years, but even though you can now get artisanal haloumi fries and an avocado latte to accompany the music, there are some constants – a significant likelihood of mud, and dodgy drugs.

Woodstock is known for its bad brown acid, but in 2018 the bad drug is likely to be pentylone, a substituted cathinone based on the active ingredient in the herbal stimulant Khat. Developed in the 1960s, pentylone is one of the many cathinone-derived substances that have hit the illicit drug market in recent years. You may have heard of some of its relatives – mephedrone, or meow meow, was one of the better known ‘legal highs’ in the UK, before the Psychoactive Substances Bill outlawed their sale and possession in 2016.

Illicit drugs are sometimes bulked out, or ‘cut’, with other substances. Dealers can increase their profits by mixing the pure drug with cheap adulterants. Everyday household powders such as baby powder and cornflour are thought to be common cutting agents, as well as cheap pharmaceuticals like aspirin and chloroquine. Cocaine is often cut with local anaesthetics like lidocaine – they’re cheaper and easier to obtain, but behave in similar ways to the real thing.

Novel psychoactive substances like pentylone and other cathinone derivatives have similar effects to MDMA. Cutting with pentylone can, therefore, allow manufacturers and dealers to make a batch of MDMA go further, or they can substitute the original drug entirely. The knock on effect is that drug users can have no idea of the compound or the dose they are getting. Should they then run into trouble and need medical help, the emergency services may then be misled, and treat for a reaction to the wrong drugs.

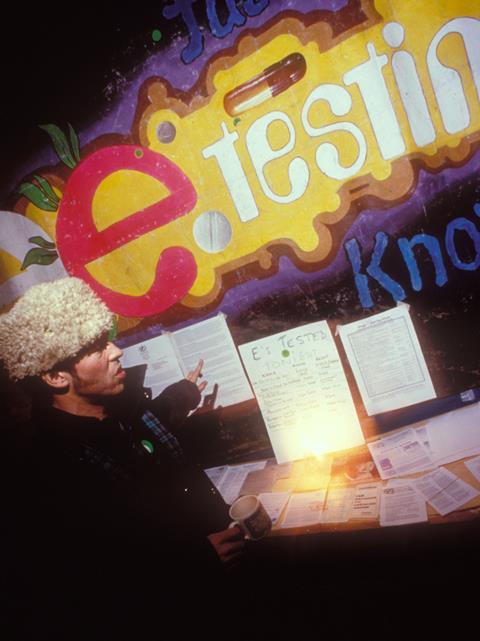

The Loop is a not-for-profit company dedicated to harm reduction at festivals and nightclubs. For the last few years the team has used its chemical and forensic knowledge to test drugs for agencies and for the public. In 2018, the team tested thousands of drug samples at 12 festivals as part of its multi-agency safety testing, or Mast. The Loop has also been recording data throughout, and are hoping to publish an in-depth report next year. One thing they have noticed is a recent trend of pentylone being sold as MDMA or ecstasy pills.

Last year we spoke to Fiona Measham, professor of criminology at Durham university and director of The Loop.

Fiona Measham

Generally, we find that most people who are going to nightclubs or festivals, the drugs that they are most likely to want to take are ecstasy, cocaine and ketamine. Generally, they’re quite easily available, quite high purity at the moment and quite low price. So people tend to get what they want, what they expect, and we found that around nine in 10 people have got the drugs that they expect.

About one in ten are not.

Some of those will have totally inert fillers – there’ll be no psychoactive effect at all. Some of them will have been mis-sold other drugs, for example ketamine might be mis-sold as cocaine. You might find that caffeine has been mis-sold as cocaine, things like that. We do find a small number of new psychoactive substances as well.

There have been some interesting trends in relation to that. For example in 2013–14, people were mis-selling methylone , which is a cathinone, for MDMA. The base crystals look pretty similar, and the effect is not dissimilar as well. The benefit for the manufacturers and for the traffickers would be that it’s a relatively cheap class B drug that they’re smuggling across borders, and then they can sell it instead of a class A drug once they get into the UK .

That was what we used to see, but what we’re seeing instead now is, we’re not really seeing so much methylone, we’re seeing the group of drugs known as the valerones, but particularly pentylone, starting to be mis-sold as MDMA. Again, it looks not dissimilar in terms of its appearance, but in terms of its effects it is a concern because it’s a long-lasting cathinone. People might take the first pill, have a very, very slight euphoric effect and think it’s just a weak ecstasy tablet, take another one and then they will have a very large dose of pentylone which could last up to 36 hours. They’ll become agitated, they won’t be able to sleep. They could become paranoid. Even after medical treatment, they could be in a situation where they’ve got elevated blood pressure and pulse.

So it’s a concern that some of these new psychoactive substances are being mis-sold as what you would call the classic, conventional street drugs like ecstasy, cocaine and ketamine. Generally, amongst these groups there’s less interest in psychoactive substances, it tends to be about them being mis-sold. So one of the useful things about Mast is that we can identify that mis-selling on site.

Ben Valsler

On-site testing allows users to make better-informed decisions, leading to some taking lower doses or ditching the drugs entirely. This year, testing and identification allowed festival organisers to publish warnings about pentylone being sold as MDMA during their events. Though some do criticise the idea of drug testing, saying it gives people a false sense of security. And as The Loop points out, the best way to mitigate risk is not to take any drugs at all, so perhaps it’s best to just eat your artisanal cheese on toast and enjoy live music in the mud.

Next week, Mike Freemantle joins us with the pigment that links your blue jeans to our ancient ancestors.

Michael Freemantle

The cultivation of these indigo-producing plants throughout the world can be traced back several thousand years. The dye is therefore probably the world’s oldest colouring material. It has been used not only for body art, but also in artists’ paints, for printing and especially for colouring textiles.

Ben Valsler

Join Mike next time for the story of indigo. Until then, feel free to get in touch: email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for listening.

No comments yet