Meera Senthilingam

This week, some fateful chemistry with Anna Lewcock.

Anna Lewcock

Serendipity has played her hand throughout the history of science - the right person in the right place at the right time, the stars align just so, and discoveries and theories emerge that otherwise might have lain buried for years and years. The discovery of prolactin is one such event.

Prolactin is a peptide hormone produced by the anterior pituitary gland, primarily known for stimulating milk production following pregnancy. In the early part of the 20th century, the anterior pituitary was a bit of a mystery. It had been suggested that extracts from the gland could stimulate lactation, but the specific substance causing the effect remained unknown.

Around this time, a young American by the name of Oscar Riddle was studying for a PhD in zoology under Charles Whitman at the University of Chicago. Whitman’s interest lay in bird evolution, and he set Riddle to work looking at patterns on bird feathers, pigeons in particular. Riddle later said that Whitman had been like a father to him, and on his death Riddle took on the mammoth job of collating and organising Whitman’s extensive research for publication. But it was his continuation of the work with pigeons (including caring for a large colony kept at Whitman’s home) that is key to the story of prolactin.

In the early 30s Riddle, by this point an experienced endocrinologist, became aware of reports of the milk-inducing property of pituitary extracts, and decided to investigate. Naturally, he used his pigeons in his research. Riddle found that following injections of extracts from the anterior pituitary, the pigeons’ crop sac would thicken and start secreting milk. He was then able to use this test as a bioassay, enabling him to isolate fractions from the extracts and firmly establish that the milk stimulating substance was distinct from other growth-promoting and gonad-stimulating properties found in anterior pituitary extracts. The crop sac assay allowed Riddle to obtain a relatively pure sample of the substance, which he named ‘prolactin’, deriving from the Latin root for ‘milk’. Without the crop sac assay, it could well have been many more years before prolactin was isolated.

Prolactin has more actions than all the other pituitary hormones combined, with over 300 different biological activities reported

And indeed, it remained the only available assay for the hormone for several decades, until the development of a radioassays for prolactin in the late 1960s. At this time, there was also considerable doubt that prolactin existed in humans. Repeated attempts to purify the hormone from human pituitary glands had failed, and some believed that growth hormone was responsible for stimulating lactation in our species. But by the early 70s, researchers in H.G. Friesen’s lab in Canada had managed to isolate the human form. In protein synthesis studies they obtained radioactive peaks similar, but not identical, to human growth hormone. They concluded that an unknown peak must indicate the long sought-after prolactin.

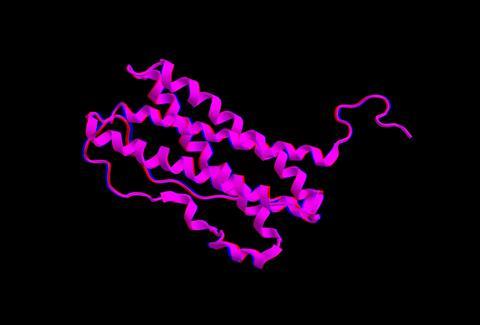

Today, we know far more about the protein. There are three main forms in terms of size, known as little, big, and big-big (clearly named from the same school as the seven dwarves). Little prolactin is the most common form, a single-chain polypeptide of 198 amino acids with a molecular weight of around 23kDa. And it does far more than its name suggests. Prolactin has more actions than all the other pituitary hormones combined, with over 300 different biological activities reported, ranging from effects on behaviour, metabolism and reproduction to immune regulation, tumour growth, and metamorphosis in amphibians. It’s used in medical tests to investigate pituitary disorders, fertility problems and other conditions that affect the body’s prolactin levels.

So as with Darwin’s Origin of the species – pigeons played a surprising role in scientific discovery. Had Oscar Riddle not decided to continue the legacy of Whitman’s work with pigeons, it could have been many more years before prolactin was purified and characterised, and the nature of this fascinating protein would have remained hidden.

Meera Senthilingam

Thankfully it didn’t. Science writer Anna Lewcock there with the fortuitous chemistry of prolactin. Next week, cup of tea? Or maybe more…

Brian Clegg

If your only association of ‘tannin’ is that stuff that makes tea taste astringent, you’ve got some surprises to come. Tannins are found in a number of plants and have turned out to be surprisingly useful to us.

Meera Senthilingam

Discover how useful with Brian Clegg in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

1 Reader's comment