‘Business as usual’ scenarios suggest toxic emissions could kill millions of people in the near future

Almost seven million people could die each year around the world because of outdoor air pollution unless strict emission controls are introduced, suggests a new study based on a global atmospheric chemistry model.

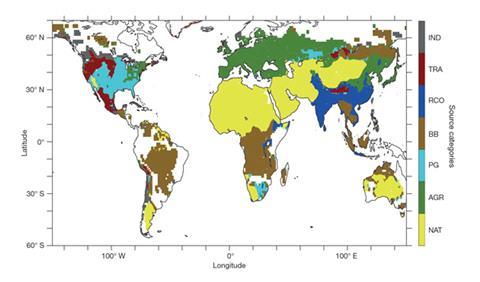

Jos Lelieveld, of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues, combined the model with population statistics and health data to estimate premature deaths caused by pollutants such as ozone and fine particulate matter of less than 2.5µm, termed PM2.5, which arise from sources as diverse as coal power stations, agriculture and the burning of wood or dung in homes.

The model shows that more than 3.3 million people a year die prematurely from inhaling the pollutants, from diseases affecting the heart, circulation and lungs. The largest impact on mortality worldwide is from the residential use of smoky fuels in parts of China and India for cooking or heating.

In much of the US and some other countries, emissions from power generation and traffic contribute the most toward mortality from air pollution, while, perhaps surprisingly, in Europe and Russia the biggest culprit is agriculture. This, explains Lelieveld, is because ammonia released from fertilisers combines with gaseous emissions from traffic exhaust and power stations to produce sulphate and nitrate particles.

Commenting on the new work, Aaron Cohen, Principal Scientist at the Health Effects Institute in the US, which plays a central role in estimating the burden of disease due to air pollution in the international Global Burden of Disease (GBD) collaboration, says: ‘This study is quite well done and represents a very welcome trend towards focusing on the burden of disease attributable to major sources of air pollution, sources which must be controlled in order to reduce the huge burden of disease attributable to air pollution worldwide.’

Cohen points out that the current study used GBD estimates from 2010, but that new estimates from 2013 have just been released. ‘Had they used the latest estimates the overall conclusions would have been similar, though the estimated burden of disease would have been somewhat lower: millions of deaths and lost years of healthy life attributable to ambient PM2.5 air pollution worldwide with the largest burdens in East and South Asia.’

No comments yet