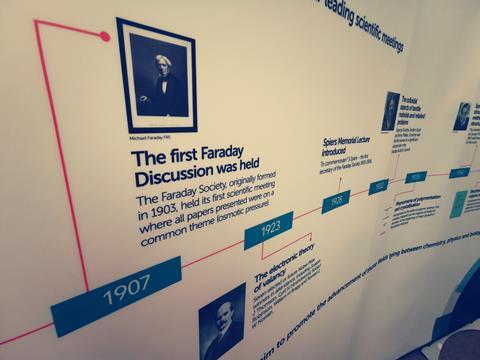

Since 1907, leading researchers from across physical chemistry have presented and discussed cutting-edge science at the Royal Society of Chemistry’s (RSC’s) Faraday Discussions. In February, the series celebrated its 300th meeting – yet another milestone for the unique format where new ideas and collaborations emerge in the midst of the meeting itself.

At most scientific conferences, speakers will have up to an hour to present their latest work, with maybe five minutes for questions at the end if the speaker doesn’t run over. The Faraday Discussions flip that model, with strictly timed five-minute presentations and significant time allocated for questions, debate and in-depth discussion. This format means the discussions have been the birthplace of several significant advances in physical chemistry. The technique of laser flash photolysis – an essential technique for studying fast reactions – was unveiled at a Faraday Discussion in 1950, while a 1971 meeting on conductivity in organic materials was instrumental to the development of molecular electronics such as organic LEDs.

The discussions have even been cited as having spawned entirely new fields of research. ‘You could argue that Faraday Discussions have founded fields like polymer chemistry or molecular electronics,’ says Claire Vallance, president of the RSC Faraday division and professor of physical chemistry at the University of Oxford, UK. ‘In my own field, there was a Faraday Discussion in 1986 that led to the invention of velocity map imaging, which is the main technique that I use in my research. I think it’s absolutely brilliant that we’re on 300 meetings. It’s proven to be a format that people really like.’

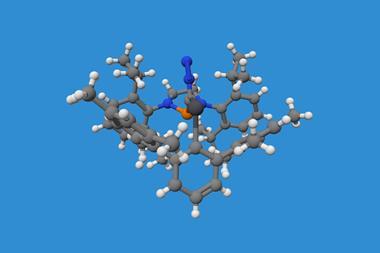

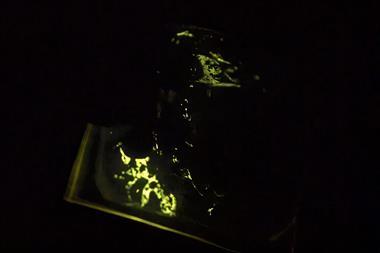

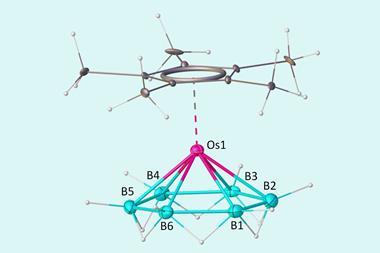

The 300th discussion, held at Burlington House in London, UK, was on the subject of hot electron science and plasmonics. ‘It’s a really great moment to reflect on what’s been done over the past 100 years,’ says John Seddon, chair of the RSC committee that oversees the meetings. ‘It’s extremely fitting that the 300th anniversary should be on the subject of plasmonics, as Faraday himself was one of the fathers of the field.’

To encourage as many delegates as possible to take part in the discussions, the research papers written by the speakers are sent out in advance of the meeting, giving those who are perhaps less confident the time to prepare their questions. This is a big draw for those early on in their academic careers – not only do they get to witness some of the biggest names in their field engage in full and frank discussion, they can get involved themselves. ‘The format allows people to see clearly what the key points of contention are in that field,’ Seddon explains. ‘It can be quite heated at times – not everybody agrees on the interpretation of certain data.’

Bart de Nijs, an early career fellow at the University of Cambridge, UK, argues this is part of the appeal. ‘I think it’s OK if the discussions get intense. The more that is said, the sooner you get past the formalities and then real answers come out. The more discussion the better, I think.’ De Nijs is a veteran of the series, having attended three meetings to date. ‘If you’re going to go through the effort of getting together all of these highly educated people, you might as well ask them for their input. You know your research but you’d love to have their input as well. Often science is disseminated in a one-way flow of information. You publish your paper, you get some peer review comments but not much conversation going back and forth. In a situation like this everyone can chip in and provide some very valuable insights.’

Wendy Niu, programme manager for the RSC Faraday division, agrees. ‘It’s a really exciting event to attend. It’s not very often that you get to be at the 300th iteration of anything, and to come to an event with such a long history is really very exciting. I think it’s great to celebrate this unique format where people get the chance to discuss the work they’ve been doing. Almost everybody can pinpoint a discussion where their field really took off and it was instrumental in driving their science forward. It’s really important for us to build on this programme, to listen to the community about what they want and make sure we keep on delivering.’

The latest volume of Faraday Discussions is published here. The next meeting, on nanolithography of biointerfaces and will be held at Burlington House from 3–5 July 2019.

No comments yet