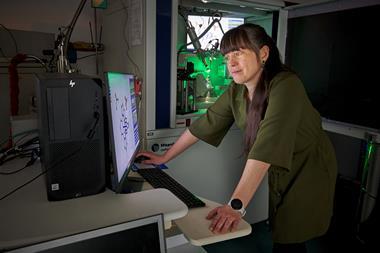

Marelene and Geoff Rayner-Canham examine one of Dorothy Hodgkin’s mentors, who never studied at school or university

Everyone ‘knows’ that the pioneering female x-ray crystallographer was Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, 1964 Nobel laureate in chemistry. However, she was not the pioneering female crystallographer: that honour goes to Polly Porter. In fact, Porter was one of Hodgkin’s mentors as Guy Dodson, once Hodgkin’s post-doc, later wrote in her obituary: ‘She was anxious to return to crystallography. She was greatly encouraged in this by Dr Polly Porter, a Research Fellow at Somerville, who had worked for years measuring and cataloguing crystals.’

Porter was a leading expert on the morphology of inorganic crystals. When Hodgkin needed to report crystallographic measurements in the 1950s, it was Porter who provided them. Solely on the basis of her research work, Porter was awarded BSc and DSc degrees by Oxford University. Yet she had never attended school , nor completed any university courses. So, who was this Dr Polly Porter who mentored Hodgkin and why is she barely known today?

Born in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, in 1886, Mary Winearls Porter was known by all as ‘Polly’. Her father, a newspaper journalist and editor, believed that education was unnecessary for women and as a result, she only received a basic home education in reading and writing.

From 1901 to 1902, Porter was in Rome with her sick mother while her father held an appointment as special commissioner in Cuba and Puerto Rico. Family friends took her to see the ruins of the surviving Roman buildings. She was in awe of the different colours of the marble used in their construction, and she collected fragments to make a collection of marble types.

The reviewers could have had no idea that ‘Miss Porter’ was just 21 years old and had no academic qualifications

The Porter family then returned to the UK and settled in Oxford. 16-year-old Porter discovered that about 1000 specimens of marble varieties, the Corsi Collection, were housed at the University of Oxford Natural History Museum. She took her samples to identify them by comparison with those in the collection. This was difficult, as in the 75 years since the collection arrived, it had become begrimed, and labels and samples had been lost.

Porter’s repeated visits to look at the Corsi Collection were observed by Henry Miers, a professor of mineralogy. He asked Porter if she would be willing to clean the specimens and re-identify them by translating the original catalogue from Italian to English. She eagerly agreed. Impressed by her intelligence and enthusiasm, Miers pleaded with Porter’s parents to let her remain at Oxford to be coached for the university entrance examinations; unfortunately, the plea was not successful.

During her time with Miers in Oxford, Porter wrote a monograph on the varieties of marble types, published in 1907 and titled What Rome Was Built With: A Description of the Stones Employed in Ancient Times for its Building and Decoration. Glowing reviews appeared in several academic journals, but the reviewers could have had no idea that ‘Miss Porter’ was just 21 years old and had no academic qualifications whatsoever.

During the winter of 1910–11, Miers introduced Porter to Alfred Tutton, who asked her whether she would like to work in his laboratory in London. She accepted enthusiastically. Her research involved the synthesis of crystals of new ionic compounds containing two different cations (now called Tutton’s salts) and studying the effect of changes in the cation identities on the crystal form. The work was published in the Journal of the Mineralogical Society in 1912 with Porter as co-author.

The Porter family resumed its travels, first back to the US where Porter catalogued the mineral collection of the National Museum in Washington, now known as the Smithsonian. Then to Germany, where she worked on the Mineralogical State Collection in Munich. Back in the US again, Porter worked on the mineral collection at Bryn Mawr College under Florence Bascom, the most prominent American woman geologist of the period, who was to become her life-long friend.

There was a great row about having a woman on the council but the majority agreed in the end

In 1914, Bascom arranged for the German mineralogist and crystallographer, Victor Goldschmidt at the University of Heidelberg, to take on Porter as a research student, despite her lack of formal education. Goldschmidt wrote to Bascom that Porter’s research work was outstanding. In October that year, however, Porter wrote to Bascom that Goldschmidt had been unable to cope with the outbreak of war and was in a sanitorium suffering from severe depression. Porter continued her research, working on her own, but with opposition from other faculty; some because she was a woman, and others because of her British/American nationality.

In August 1915, Porter left Germany for Italy. She did not explain how this was accomplished, as Italy was on the Allied side with Britain and France in the first world war. The next month, Porter sent Bascom a postcard from Carrara where she had visited the world-famous marble quarries: ‘Yesterday I visited the quarries. It took 7½ hours walking all the time but it was most interesting … The police sent for me at Massa [where she was staying] this morning to find out why I was here but it was settled satisfactorily. Both places [Massa and Carrara] are in the war zone.’

From Italy, Porter travelled back to Oxford, starting research with the new lecturer in crystallography, Thomas Barker. The university now gave BSc degrees to students who had completed two years of research and had their thesis approved by a board of examiners. Barker agreed to be Porter’s supervisor.

In June 1918, Porter received her BSc certificate, though not a formal degree as these were barred to women until 1920. At the same time, she was elected to the council of the Mineralogical Society. Porter conveyed the news to Bascom: ‘There was a great row about having a WOMAN on it but the majority agreed in the end.’

Like so many of the single women researchers without formal academic positions, money was always a concern for Porter. Fortunately, with glowing supporting letters from Miers and Tutton, she was awarded the valuable Lady Carlisle Research Fellowship at Somerville College, Oxford. Porter’s research on inorganic crystals, their synthesis, morphology, and optical properties resulted in a series of publications, mostly with her as sole author. As a result of her prolific and comprehensive crystal studies, Porter was awarded a DSc degree in 1932.

Porter has a strong claim to being the starting-point of the lineage of female British x-ray crystallographers

It was crystallo-chemical analysis which became Porter’s obsession: determining the chemical composition of a crystal by means of crystal classification and precise measurements of crystal faces and angles. One of Porter’s many successes in this context was the identification of tiny crystals found in a deceased person’s lungs as the mineral struvite.

Porter’s later life-work came to revolve around the completion of the Barker Crystallographic Index which was intended to provide a comprehensive database for crystallo-chemical analysis. This goal had originated with Barker. To aid him, he enlisted Porter, together with Reginald Spiller. Barker died in 1931, but Porter and Spiller continued with the work, and volume one was published in 1951.

The second volume was published in 1956 and, following Spiller’s death in 1954, for the third volume Porter acquired a new co-author, L W Codd. The three volumes together contained crystallographic data on a total of 7300 crystalline substances. Codd subsequently wrote a paper on the Barker Index as an analytical tool, but nowhere in the article did he mention Porter or her contributions.

Why, then, has her work been forgotten? This was best explained in the History of the Oxford University Geology and Mineralogy Department: ‘Remarkable document though [the Barker Index] undoubtedly is, the fact cannot be disguised that its practical value has been very limited, due to the rapid development since the late 1920s of x-ray diffraction methods in crystallographic analysis, which generally provide quicker and more reliable results, as well as requiring less specialised experimental skills on the part of the investigator.’

Porter’s later life-work came to revolve around the completion of the Barker Crystallographic Index which was intended to provide a comprehensive database for crystallo-chemical analysis. She worked on the three-volume index with Barker, Reginald Spiller and later L W Codd. In a subsequent article Codd wrote about the index, he failed to mention Porter or her contributions. The rise of x-ray diffraction techniques from the 1920s onwards means the index’s practical value was only limited.

Porter was appointed honorary research fellow of Somerville in 1948. Her last work came full circle, back to revising, updating and reorganizing the Corsi Collection. Porter died at Oxford in 1980, age 94.

Porter’s life-story was incredible, commencing with a lack of formal education and concluding with a BSc, a DSc and an honorary research fellowship. Yet how does her work fit in with the narrative of women’s roles in British x-ray crystallography?

Michelle Francl, a chemist at Bryn Mawr, proposed in a 2014 article on women in crystallography that Porter played the key role in opening British x-ray crystallography to women. ‘I suggest that Bascom at Bryn Mawr and Porter at Somerville were the seeds from which the large crop of women in x-ray crystallography sprouted. Women were not being escorted into a new field by kindly men such as the Braggs, as much as they were seeking out exciting opportunities within a field they already inhabited.’

Porter has a strong claim to being the starting-point of the lineage of female British x-ray crystallographers. In Georgina Ferry’s biography of Hodgkin, she commented: ‘She [Porter] also assisted with teaching a practical class in crystallography for undergraduate chemists. Dorothy came to know her through these classes and her Somerville connection, and found her “a great encouragement”.’

In conclusion, Porter’s own work in later years, sadly, proved to be a backwater of crystallographic science. Nevertheless, her life-story is inspiring in the extreme and it is our contention that she was the first of the pioneering women in this field and an inspiration to Hodgkin, future Nobel laureate.

Marelene Rayner-Canham and Geoff Rayner-Canham are historians of chemistry at the Grenfell campus of Memorial University in Canada

Acknowledgement

Kate Long, research services archivist in the special collections at Smith College in Massachusetts, US, is thanked for digitising the 295 pages of correspondence from Mary Porter to Florence Bascom for the authors’ research.

No comments yet