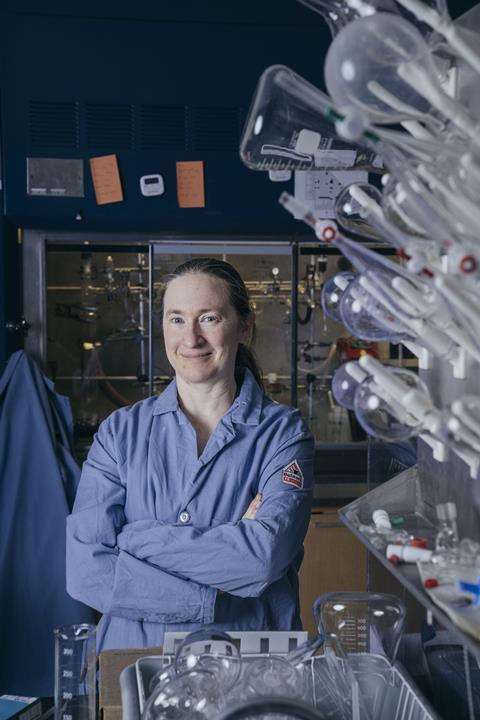

One-time gymnast Melanie Sanford has made a name for herself in catalysis and organometallic chemistry. Rebecca Trager charts her path to success, from her mentors to her mentoring

- Early life and inspiration: Melanie Sanford grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, in a politically active family. Her interest in chemistry was sparked by an inspiring high school chemistry teacher, leading her to pursue a career in science.

- Academic and research journey: Sanford attended Yale University, where she engaged in research on carbon–fluorine bonds. She later pursued a PhD at Caltech under Robert Grubbs, focusing on organometallic catalysts. Her postdoctoral work at Princeton University further shaped her research interests.

- Professional achievements: Sanford is a renowned chemist at the University of Michigan, known for her work in catalysis and organometallic chemistry. She has received numerous accolades, including the Janssen Prize for Creativity in Organic Synthesis, becoming the first woman to win this award.

- Mentorship and legacy: Throughout her career, Sanford has mentored over 60 PhD students and 30 postdocs. She emphasises the importance of a diverse and inclusive research environment and continues to explore new areas in chemistry, including electrochemistry and radiochemistry.

Summary generated by AI and checked by a human editor

Melanie Sanford, an organometallic chemist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, US, remembers standing in front of her elementary school classroom around 40 years ago, wearing a pink Jordache dress and representing then-US vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro – the first woman to be nominated for such a role – in a mock class debate. Sanford delivered passionate arguments in favour of the Walter Mondale–Ferraro ticket. Back then, her aspiration was to be the first female president of the US. This remains technically possible following the 2024 election, but for now she is shattering glass ceilings in the world of chemistry.

Sanford was raised in the US seaport city of Providence, Rhode Island, and her parents were very politically active. They took her to campaign events and other political activities from the time that she was very small. ‘When I was a kid, I remember lots of times going out with my mom for political campaigns, knocking on doors, handing out pamphlets,’ she recalls. ‘That was … a big part of my childhood.’

Her parents were not scientists, but they were dedicated readers and learners and passionate about political issues like women’s rights. Her mother was a political science professor at a small university nearby, and her father owned a small business selling rare books. Sanford wasn’t particularly drawn to science or chemistry until her third year of high school, when an amazing teacher of an Advanced Placement chemistry course entered her life.

‘This chemistry teacher was just incredible … and I thought it was fantastic,’ she recounts. ‘He was really encouraging; the Providence public school system was really encouraging.’ Sanford won an award for being a top science student in her high school class. ‘It made me think “Wow, I do like science, and I guess people think I’m pretty good at it,”’ she says.

From there, Sanford went to Yale University in Connecticut, and found herself taking organic chemistry as a freshman, surrounded by pre-med students for whom the course was a prerequisite. She considered pursuing medicine but decided against it because she didn’t want to blindly follow the pack, and didn’t think being a doctor was the right career for her. Instead, she got involved with research.

In the chemistry lab of Robert Crabtree, Sanford focused on developing different ways to break carbon–fluorine bonds, which are considered among the strongest single bonds in chemistry because of the high electronegativity difference between the two elements. She even ended up co-authoring a paper from this undergraduate research.

Salad days with carbon–fluorine bonds

‘The research that I did there at Yale ended up being essentially developing a way to functionalise Teflon surfaces by using a mean charge-transfer complex,’ Sanford explains. This is a subject that remains topical today because of concerns about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – a family of an estimated 15,000 chemicals that are persistent, highly mobile and have been linked to a range of environmental and health problems.

The widespread PFAS contamination of the environment and extensive human exposure are now well documented. But at that time, in the 1990s, Sanford says the worry was more about atmospheric contamination by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – which also contain carbon–fluorine bonds – rather than PFAS in the environment or groundwater.

Carbon–fluorine bonds as a research topic has stuck with Sanford throughout her career. In fact, she is currently working on developing ways to make them for pharmaceutical and agrochemicals synthesis purposes (for more on fluorine in drugs, see Putting the F in pharma).

While at Yale, gymnastics consumed a significant amount of Sanford’s time when she was not in the classroom or research lab. She has been a gymnast almost her entire life, and immediately joined the university’s gymnastics team after enrolling. ‘We had practice – training – every day, competed on the weekends during the season, travelled all over the country,’ she recalls. ‘So that was a lot of time commitment, and my main hobby at the time.’

Sanford also spent several summers during college interning at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC, studying biosensors. She really enjoyed of living in the US capital. ‘That was a seminal experience for me … and I met so many people,’ Sanford recalls. ‘And just being in Washington over the summer, with all of the political and cultural activity, in addition to the science, were really impactful on me.’

The summer after graduating from Yale with a bachelor’s and master’s degree in chemistry, and before entering graduate school, Sanford lived in Boston, Massachusetts, with some friends and worked at the Au Bon Pain sandwich chain. It was a minimum wage job but was quite impactful. ‘I was a “salad girl,” so I made salads, but they wouldn’t let me make sandwiches,’ she recalls. ‘At least back then at the Au Bon Pain that I worked at, making sandwiches was a man’s job. So even in that setting … there was a lot of sexism.’

Her brief summer salad stint ended when she entered Caltech to pursue a PhD in inorganic chemistry. She joined the lab of Robert Grubbs, who later shared the 2005 chemistry Nobel prize for his metathesis research.

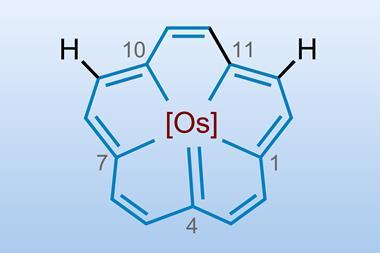

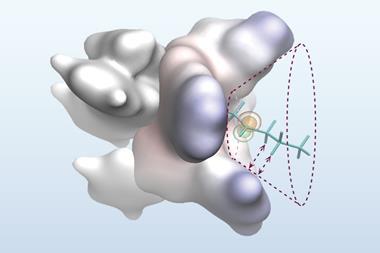

Grubbs – who died in 2021 – was well-known for his work in olefin metathesis, a chemical reaction where carbon–carbon double bonds in molecules are rearranged to create new carbon–carbon bonds using ruthenium-based catalysts. This reaction was especially interesting to Sanford because it involves organometallic catalysts – ruthenium complexes with a metal–carbon bond. While working with Grubbs, Sanford studied the mechanisms by which those organometallic catalysts promote carbon–carbon bond-forming and -breaking reactions.

Moving from designing to dissecting

When she arrived at Caltech, Sanford was initially focused on designing new catalysts, spending her first several years there trying to create new ruthenium catalysts for olefin metathesis that worked better than previous ones. ‘I made lots of different ruthenium complexes and made various hypotheses about how they could be better catalysts than the existing ones,’ she recounts. ‘None of that was actually very successful – I made lots of molecules, but they weren’t better than the state-of-the-art.’

Eventually, Sanford became interested not just in making new catalysts but in knowing how the existing catalysts worked. Ultimately, that was the centrepiece of her PhD dissertation – a detailed study to understand how the catalysts operated, and identify the individual steps in the catalytic cycle as well as the key bond-forming and -breaking reactions.

What fascinates Sanford about metals and organometallic chemistry is that this area is full of the unexpected, ripe for discoveries and revelations. ‘In organic chemistry, there’s a pretty well-defined set of rules for how bonds to carbon form and break, and so what I really liked about the organometallic chemistry is that when you introduce a metal there’s a lot more complexity – there are a lot more opportunities to be surprised, where things can happen that you don’t expect,’ Sanford explains. She describes organometallic chemistry as ‘still a bit of a wild west.’

I got really, really good at foosball

Since gymnastics is something that is hard to continue with age, Sanford pursued a different hobby during her years at Caltech: foosball, or table football. This first took root while Sanford attended a conference in Poland that featured a big foosball competition. ‘I was really bad, and I really wanted to be able to go to conferences and be good at this game,’ she remembers.

It turned out that there was a foosball table in the Caltech faculty club, and after returning from that conference Sanford and several colleagues would go there and play the game together every Friday night, and sometimes during lunch. ‘I got really, really good at it,’ she says.

Currently, a foosball table sits in Sanford’s basement. She used to play it regularly, especially with her son who is now 16 years old. ‘I used to play a lot with him, but then he got too good, and he beat me all the time,’ she says. ‘So, then we stopped, but my dad is actually really into it too, so whenever he comes to visit there are always various tournaments and competitions.’

A happily ever after accident

But the most significant thing she found at Caltech is her husband, fellow University of Michigan chemist Antek Wong-Foy. They were PhD students there together and lived in the same student housing building. One day Sanford accidentally threw her keys into the dumpster, instead of into the purse that she was also holding. Wong-Foy was there and helped her retrieve her keys, and the rest, as they say, is history. The two have collaborated on several projects over the years involving catalysis in metal–organic frameworks, including one in 2013.

After her PhD, Sanford went directly to Princeton University in New Jersey as a postdoctoral fellow. She had planned to switch her focus slightly to bioinorganic chemistry, but her advisor J T Groves – an expert in metalloporphyrin chemistry – drew her back to organometallic chemistry, and especially to metalloporphyrin complexes.

One of the most valuable aspects of Sanford’s postdoc is that it allowed her to experience a different mentorship style. ‘When you’re a graduate student you sort of think that everywhere is like your own experience,’ she explains. ‘For me, going to a postdoc and having a very different experience with someone who … ran their group a really different way, helped me to crystallise what was going to be important for me as I had my own independent group.’

You have to be flexible in order to be successful for every person in your group

Unlike Grubbs, whom Sanford describes as ‘the most hands-off person that I’ve ever seen in the field’ and gave his students a lot of autonomy, she says Groves was much more hands-on. That difference in style helped her think about how best she might be able to mentor others. ‘What I try to do it is adjust to what different students need,’ she says. ‘You have to be flexible in order to be successful for every person in your group, because every person needs a different kind of mentorship.’

Some students thrive on lots of direction and frequent meetings to discuss progress, she observes, while others are more interested in pursuing research on their own and then meeting once they’ve figured things out by themselves. In addition, Sanford notes that students and their needs often will change over the course of their PhDs, so a good mentor must be observant and adaptable.

Following her postdoc, Sanford became an assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in the summer of 2003. Almost immediately, she found a fantastic mentor in senior colleague Ed Vedejs, a Latvian-American chemistry professor who joined the faculty in 1999, retired in 2011 and passed away in 2017.

Vedejs helped guide and mentor her through being an assistant professor. ‘He was incredible,’ she says. ‘He helped me with things like grant submissions, writing papers and thinking about how to build my career…he was just incredibly supportive.’

A trailblazing mentor

Another of her pivotal mentors is Karen Goldberg, who is currently a professor at the University of Pennsylvania but was formerly at the University of Washington. ‘She is one of the incredible women in organometallic chemistry – a real trailblazer in the field,’ Sanford says.

A few years after becoming a professor at the University of Michigan, Sanford’s students invited Goldberg to give a talk there, and the two women ended up having dinner and talking for several hours. Goldberg told her about a new catalysis and organometallic chemistry centre that she was starting up, funded by the US National Science Foundation, and invited her to become part of it. Sanford was involved with the Center for Enabling New Technologies through Catalysis for about a decade, and because of this participation she met luminaries in the field and collaborated with many of them.

‘I can’t say enough about how much her mentorship, and the path that she blazed before me, impacted me as a scientist,’ Sanford says of Goldberg, who brought her into that centre grant early in her career. It proved to be an extremely important stepping stone to networking with the right people, developing her ideas, and thinking more broadly.

At the University of Michigan, Sanford was promoted to associate professor with tenure in 2007, and to full professor a few years later. She has stayed at the university for more than two decades primarily because of extraordinary colleagues from the beginning. ‘It is fun to come to work every day, because I work with amazing people, and we recruit fantastic graduate students – I have always had some of the best students in the country in my group,’ Sanford says. Right now, there are approximately 20 researchers in her lab, including about 15 graduate students, and a couple of postdocs and undergraduates. She has taught and mentored more than 60 PhD students and 30 postdocs.

She makes it clear that any challenges she has faced as a woman in chemistry pales in comparison to women who entered the field, and other areas of science, one or two decades before her. ‘From when I started to now, there’s been an enormous growth in women in the field,’ she says. ‘Definitely there are times when people will say, imply, you only got invited for this talk, or won this award, or got this honour, because you’re a woman,’ Sanford acknowledges.

But she has not experienced anything resembling the stories about the blatant discrimination faced by that women who were in science 10 or 20 years before her. ‘Many of the trailblazers, like Karen Goldberg and others before her, paved the way for me to have relatively little of that in my career,’ Sanford states.

All these years later, she is still into gymnastics but now as a spectator. ‘The University of Michigan has an amazing collegiate gymnastics programme – they won the national championship a couple years ago,’ Sanford notes. She follows it closely and attends most of the meets. Back in August 2018, the US gymnastics national championship was held in Boston at the same time as an American Chemical Society conference. Sanford bought tickets to the event and watched megastar Simone Biles, among others, compete there.

Shattering glass ceilings with creativity

Meanwhile, Sanford herself is achieving superstar status and breaking barriers. Last year, she became the first woman to receive the Janssen Prize for Creativity in Organic Synthesis in the almost four decades since the award’s inception. The prize is presented every two years to a chemist under the age of 50 who has made a significant contribution to the field of organic synthesis. She received the award for her outstanding contributions to the development of mild and inexpensive fluorination processes as well as to new transition metal-catalysed C–H functionalisation methods.

‘I was shocked and just incredibly honoured to win that, and to be the first female recipient,’ Sanford states. ‘Hopefully it takes care of that milestone such that there will be a greater diversity in people winning the award in the future,’ Sanford says.

She describes the list of previous winners of this award as ‘the absolute top people in the field,’ noting that it includes Nobel prize winners – such as Barry Sharpless and David MacMillan – and ‘many people who are going to win the Nobel prize’.

Sanford’s career has surpassed even her greatest expectations. ‘If college me saw me now, I don’t think that she would believe it,’ she tells Chemistry World. Her most significant legacy, she says, are the scientists she has mentored over her career.

Looking ahead to a legacy

‘Being able to go to conferences, universities or companies and see the people that you trained going in so many different directions and doing so many incredible things is really amazing,’ Stanford says. ‘I could retire tomorrow and feel satisfied with my career, mainly because I know that these remarkable people are out there doing fantastic things.’

Her research group has always been very diverse in terms of nationalities, backgrounds, gender, race and more, and she has worked hard to create a supportive and collaborative environment.

‘It’s not just the scientific training, but also the training in how to run a really diverse and inclusive group that hopefully will be propagated forward by many of the students that I’ve had in my lab and their independent careers,’ she states.

I could retire tomorrow and feel satisfied with my career

Looking forward, Sanford is confident that there is a lot more exciting chemistry to be explored at this border between organic and organometallic chemistry. ‘We’re doing a lot of things now in electrochemistry, photochemistry and radiochemistry – at the interface of inorganic and organic,’ she says.

Although her career was built on a foundation of studying mechanisms and intermediates, Sanford has branched out in numerous directions. Her team is now pursuing areas like radiolabelling, new positron emission tomography tracers and making materials for redox flow batteries. They are also collaborating with companies like Dow to develop new methods for synthesising agrochemicals, and to design a range of novel and modular in situ photocatalysts that enable very challenging reactions, like the C–H amination of benzene with benzene as the limiting reagent.

Sanford emphasises that none of those efforts would be possible without that groundwork of understanding how chemical reactions work. She still has many of the same scientific interests, including understanding organometallic reactivity, but says increasingly her collaborations are building from there and growing.

‘Taking the core of expertise that I have and applying it in new areas is how you grow as a scientist, and that’s what I’ve tried to do throughout my whole career,’ Sanford concludes.

Rebecca Trager is senior US correspondent for Chemistry World

No comments yet