The synthetic element berkelium has been trapped between two carbon rings to create berkelocene for the first time, one of the heaviest organometallic structures ever created.

Berkelium, element 97, is highly unstable and has largely remained a mystery since its discovery at its namesake Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, US, in 1949. Only two nuclear reactors in the world can produce it and, unlike its neighbour californium, it has no known uses, which means samples are scarce and generally unavailable to researchers. To date, only a handful of berkelium complexes have been made, despite the potential for the research to help further nuclear recycling.

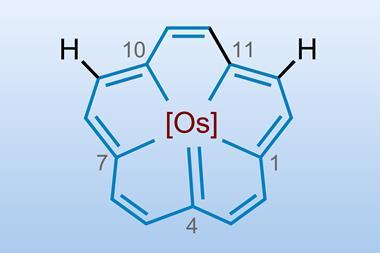

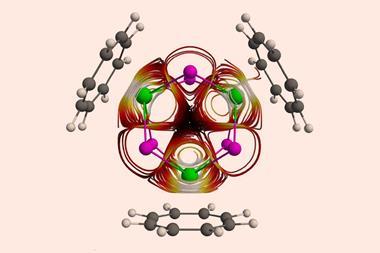

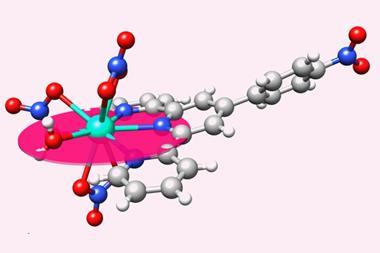

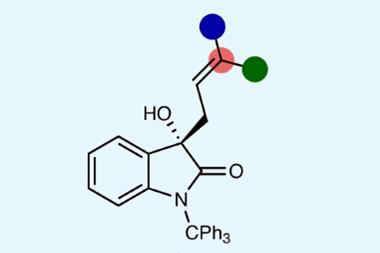

This latest effort, by a team at Berkeley Lab, the neighbouring University of California, Berkeley, the University of Buffalo, US, and Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Romania, adds to that growing tally and further expands our understanding of actinide bonding and characteristics. To do so, the researchers created ‘berkelocene’, by trapping a berkelium atom between two cyclooctatetraene (COT) ligands, effectively forming an organometallic sandwich, a technique pioneered in the 1960s to trap lighter actinides such as uranium and plutonium, and more recently to create the heavier californocene. Berkelium’s position as the eighth actinide makes it particularly enticing, as reduced inter-electron repulsion would make a 4+ charge more stable than its neighbours.

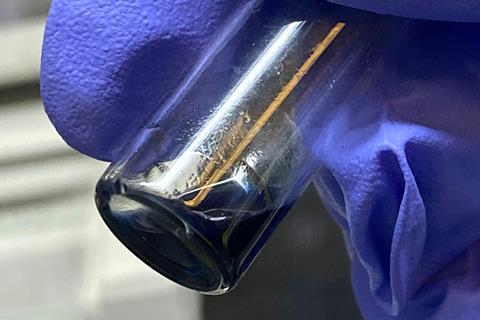

However, unlike these widely available elements, the rarity of berkelium meant the team had little breathing space for their experiment, even with the donation of an additional supply of the element from Thomas Albrecht’s group at the Colorado School of Mines. The crystals also had to be created in anaerobic conditions, in a protected environment to shield the team from radioactivity and rapidly to combat berkelium’s short radioactive half-life.

To overcome the challenges, the team first investigated the best COT ligand for the attempt using the lanthanide cerium. Then, the team produced their complex using just 0.3mg of the radioisotope berkelium-249, which has a half-life of just 330 days.

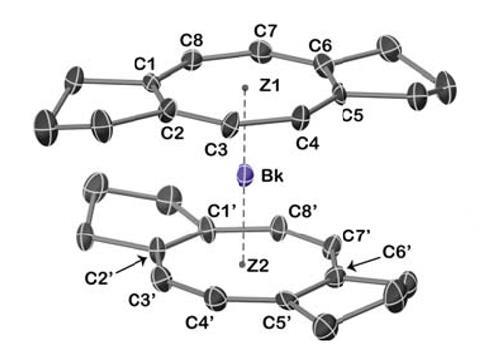

The team then used single-crystal x-ray diffraction to confirm the berkelocene’s coordination chemistry, showing the formation of a tetravalent berkelium ion between the ligands, supported with stable covalent berkelium–carbon bonds. Ultimately, the complex resembled those synthesised with similar actinides, such as uranocene; however, the team found Bk4+ behaved differently to similar complexes predicted to be formed by terbium, its equivalent in the lanthanide series. ‘This is why this work is so cool,’ enthuses Conrad Goodwin, an actinide researcher at the University of Manchester, UK. ‘It’s experimental evidence of just how different Bk4+ is to examples of 4+ lanthanide ions. While very expensive calculations might have predicted this sort of thing, without any experimental evidence to back it up, those predictions don’t give the whole story.’

The limited quantities and difficult environment mean the creation of berkelocene is an incredible feat of organometallic chemistry, although it is also bittersweet. Berkelocene is likely to be an end of an era for actinide chemistry. The elements beyond californium can only be produced a single atom at a time in particle accelerators, making it unlikely a quantity large enough to attempt such organometallic structures will be available in the future.

References

DR Russo et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adr3346

No comments yet