The fastest route to treatments may be to repurpose existing drugs – if they work

More than a dozen companies worldwide are working to develop a vaccine against Covid-19 amid the worsening pandemic. But experts estimate that will take at least 12–18 months, so doctors and companies are trying to repurpose existing drugs in the fight against the novel coronavirus.

The regulatory situation is evolving quickly. In many jurisdictions, doctors can exercise their discretion to use approved drugs off-label for other diseases, but widespread use should be backed up by evidence from quality clinical trials, and ideally approval of the regulators.

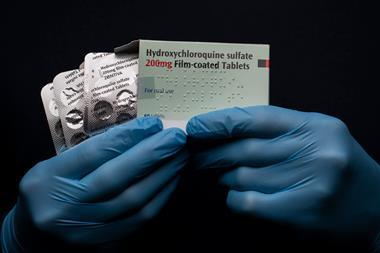

On that front, there is some confusion, as demonstrated when the US president, Donald Trump, recently proclaimed that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the antimalarial chloroquine and its derivative hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19 patients. That claim was immediately walked back by FDA chief Steven Hahn and US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci. The drugs are approved by the FDA to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, and the agency has allowed their ‘compassionate use’ against Covid-19 in dire cases. Hahn emphasised that there are, as yet, no approved treatments for Covid-19, while Fauci stressed the importance of large clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy.

Hope and hype

The clamour around chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and combinations with other drugs is mostly based on in vitro laboratory tests and small, preliminary clinical studies.

For example, a French study of 20 Chinese Covid-19 patients provided early evidence in March that the combination of hydroxychloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin might be effective against the virus. Those who received the drugs showed a reduction in viral load compared to controls, and their illness duration was reduced.

The situation is far from clear, however. In another trial involving 30 patients in China, hydroxychloroquine not did not appear to perform particularly well. Three US researchers have also issued a stark warning that the ‘anti-viral mechanisms of chloroquine remain speculative’. They asserted that ‘caution should be exercised when making premature interpretations’ because ‘clinical trials are still ongoing and interim trial data have not yet been made available.’

More about Covid-19 in our podcasts

Hear more about the history of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine on the Chemistry in its element podcast

Small trials of other antivirals have also been inconclusive. One study from China saw no significant differences between 44 patients receiving either the HIV drugs lopinavir and/or ritonavir, the Russian antiviral Arbidol (umifenovir), or no antiviral medication as the control. While another Chinese study showed that lopinavir and ritonavir did not result in any faster clinical improvement compared to patients who received standard care alone.

Avoiding ‘friendly fire’

Side effects need careful consideration in the search for drugs. An urgent guidance paper from researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, US, including genetic cardiologist Michael Ackerman, warns that chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir and ritonavir could all cause ‘drug-induced sudden cardiac death’.

These medications block one of the critical potassium channels in the heart, which increases the odds that a patient’s heart rhythm could degenerate, resulting in cardiac arrest. The same can be said for azithromycin, according to Ackerman.

Ackerman estimates that around 1% of Covid-19-positive patients would be at increased risk of such cardiac adverse events from taking these medicines. While no such incidents have been reported in any of the ongoing trials, Ackerman says there have been numerous such deaths in the FDA’s adverse event reporting system. ‘The possibility of drug-induced sudden cardiac death is not theoretical at all,’ he tells Chemistry World. ‘It will happen if we don’t identify the individuals that are at highest risk for this possibility.’

Ackerman calls the current treatment situation for Covid-19 patients ‘a total Wild West’, and says these sorts of tragic outcomes should not be accepted as ‘just part of the friendly fire in this war against coronavirus’.

Meanwhile, several drug companies across the world, including Novartis, Teva and Mylan, are ramping up production and donating tens of millions of tablets of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

Remdesivir revival

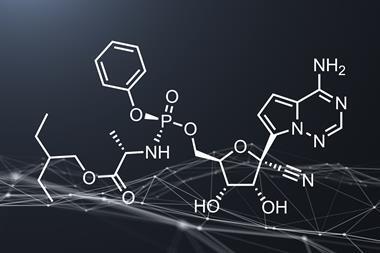

Gilead Sciences’ intravenous antiviral drug remdesivir (originally developed for Ebola, but found to be ineffective) has also shown promise in laboratory studies against Covid-19 and related coronaviruses.

While a preliminary US human trial was inconclusive, there are randomised controlled trials of remdesivir underway in China and the US. Gilead has begun two of its own randomised, open-label, multicenter studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of intravenous remdesivir for Covid-19 treatment. These trials will enrol approximately 1000 patients, primarily across Asian countries.

The FDA had granted remdesivir Orphan Drug status, which would give Gilead seven years of market exclusivity as well as grants and tax credits towards clinical drug testing costs. However, Gilead has now asked the FDA to rescind that decision. ‘Gilead is confident that it can maintain an expedited timeline in seeking regulatory review of remdesivir, without the orphan drug designation,’ the company said.

Getting a clearer picture

Fujifilm’s antiviral Avigan (favipiravir), which has been approved in Japan to treat various forms of influenza since March 2014, has also shown some effectiveness at accelerating viral clearance in a Chinese trial of 80 patients. A slightly larger trial in China, comparing umifenovir and favipiravir in 246 patients, also showed some benefit associated with favipiravir.

To generate robust data to show which treatments are the most effective against Covid-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) is leading a large international study called the Solidarity trial. The mega-trial will test four different drugs or combinations – remdesivir, a mixture of lopinavir and ritonavir, lopinavir and ritonavir plus interferon beta, and chloroquine – and compare their effectiveness to the standard of care in participating countries. The study will enrol thousands of patients across participating countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland and Thailand.

Expanding the options further

There are plenty of other avenues to explore. An international team has mapped the human proteins that viral proteins interact with. They identified 69 existing drugs and experimental compounds that bind to 66 druggable human proteins, and might therefore have some effect on the virus’s replication or transmission. A report from the American Chemical Society’s Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS), taking in patents and publications relating to Covid-19 and similar RNA viruses, identified 6 potential viral protein targets and 12 drugs to investigate for repurposing.

Meanwhile, scientists at Oak Ridge National Lab in Tennessee, US, used IBM’s Summit supercomputer to run more than 8000 simulations and identify 77 small-molecule drug compounds that might prevent the virus from infecting host cells. The researchers ranked those candidates in order of interest based in part on how likely they were to bind to the S-protein spike, which mediates virus entry into host cells.

Action on antibodies

Severe cases of Covid-19 infection cause a kind of pneumonia and significant lung inflammation. This has led to efforts to repurpose antibodies that dampen the body’s immune inflammation response. These include Roche’s Actemra (tocilizumab), whose approval has been extended to cover Covid-19 patients in China, and Sanofi–Regeneron’s Kevzara (sarilumab). Both drugs are beginning new clinical trials in Covid-19 patients.

Antibodies could also provide routes to stopping the virus from spreading. A preliminary study involving 28 Chinese patients suggests that meplazumab, a humanised anti-CD147 antibody, can improve outcomes in severe cases. The antibody binds to Basigin (CD147), which appears to be one of the proteins that the virus uses to attach to and enter cells.

‘The use of the antibody meplazumab for Covid-19 seems very positive,’ said Ian Jones, a virologist at the University of Reading, UK. ‘ It targets both the virus and the damage done by it during infection,’ he added. However, Jones noted that the treatment requires infusion while in hospital, and such drugs are not usually widely available.

Regeneron has identified hundreds of virus-neutralising antibodies and has also isolated antibodies from people who have recovered from Covid-19. The company is looking to develop a multi-antibody cocktail that can be administered preventatively before exposure or as treatment for those already infected.

Another promising lead is convalescent plasma, which the FDA has given permission for US doctors to use on critically ill Covid-19 patients. After people who have been exposed to the novel coronavirus recover and no longer have the virus in their blood, scientists could collect their blood, concentrate it, and then give it to other patients, he explained. Hahn suggested that the antibodies it contains could potentially provide a real treatment benefit.

3 readers' comments