Anita Quye explains why the sciences and the humanities aren’t as disparate as we might think

‘I didn’t realise that I had an interest in history,’ says Anita Quye, reflecting on her vibrant and varied career. ‘I just fell into this amazing world.’ Now based in History of Art at the University of Glasgow in the UK, Quye began her journey as a chemistry undergraduate two miles away at the University of Strathclyde. ‘It was a very applied programme,’ she remembers. ‘There was a purpose for doing science with a real focus on industrial applications and that got me very excited.’ So, when the opportunity arose to do a forensic toxicology PhD at the University of Glasgow, Quye seized it. Investigating new drug metabolites in bodily fluids and working alongside specialists with the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service inspired her to pursue a career in analytical chemistry and Quye saw her future in either forensics or the pharmaceutical industry. However, a serendipitous advert in Chemistry World’s predecessor, Chemistry in Britain, led her to totally change direction.

‘I saw that National Museums Scotland was looking for an organic analytical chemist to join the conservation and analytical research department,’ she remembers. ‘I knew absolutely nothing about art, archaeology and history, but they were looking for the skills and techniques I had been using during my PhD.’ Excited by this unexpected application of analytical chemistry, Quye did a little research and quickly discovered a whole new dimension to her scientific skills. The field of heritage science sits at the interface of science and the humanities, using the skills and techniques from Stem disciplines to understand and preserve cultural legacies. ‘Heritage science is absolutely founded in good scientific methodology,’ says Quye. ‘It needs a solid chemical understanding for sample analysis, but we have to be able to talk about those results in the context of their cultural heritage.’ Working as part of the museum team, Quye immersed herself in this vibrant field of research and spent the next 21 years examining artefacts from across the world to uncover their history and inform their preservation. ‘It was a fantastically interdisciplinary way of working,’ she recalls. ‘Understanding how to handle and preserve the collections, but also telling their stories.’

Museum textile analysis

This practical experience was a real asset when Quye made the transition back to academia in 2010, joining the University of Glasgow as a lecturer in conservation science. Her group studies the heritage science of coloured textiles, uncovering the history and significance of dyed materials from around the world using analytical chemistry. ‘Before Perkin’s synthetic anilines, all dyes came from natural sources which have distinctive chromophoric profiles for the botanical source,’ explains Quye. ‘These can be surprisingly specific in their chemical composition and give a fingerprint linking them to particular geographical locations.’ The group take tiny samples of museum artefacts, which they analyse with ultra-high performance liquid chromatography and photodiode array UV–visible spectrophotometric detection, comparing the chemical profiles with known dye reference samples.

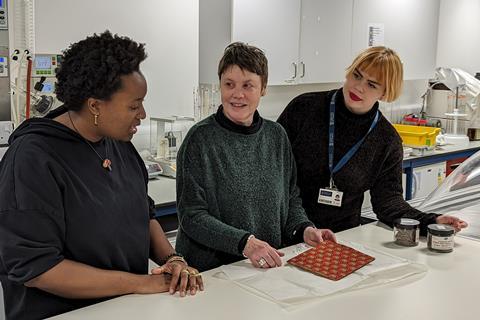

Core members of the team generally have a chemistry background, but Quye encourages collaboration with other university departments and her group often welcomes visiting members from other specialties. ‘My ethos is very much about hands-on analysis and research-led teaching,’ says Quye. ‘I think our strength comes from that interdisciplinarity and giving that space to new ways of thinking.’ Each group member is free to pursue their own particular passion and the team has studied artefacts as varied as Chinese silks, Victorian Scottish printed cotton and the first aniline dyes.

A highlight of Quye’s personal research is traditional Scottish tartans. ‘It started with a fragment from a wool suit of tartan worn by the fugitive Prince Charles Edward Stuart,’ she says. ‘There are many relics of tartan fragment allegedly from the Battle of Culloden or his flight from Scotland in 1746, but this piece was one of very few with a clear provenance.’ The suit was traced back to a rural part of the Scottish Highlands where negative post-insurrection views have skewed many aspects of the local history. Correspondingly, 19th century records claimed that dyes in the impoverished Highlands could only originate from native plants, either ladies’ bedstraw or dyer’s madder, rather than imported dyes used across Europe. Keen to uncover the real story, Quye profiled the complex chemical mixture in the tartan sample. ‘The red yarn of the prince’s fragment revealed carminic acid and other anthraquinones in the dye from cochineal, a scaled insect native to Mexico and imported to Europe,’ she explains. ‘I analysed over 100 other tartans made in Scotland between 1720 and 1822 and found carminic acid in all except one.’ This discovery challenged some of the fundamental presumptions about 18th century Scotland. ‘Cochineal was an expensive and fashionable red dye,’ says Quye. ‘The fact that it was being used in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland paints a different picture of the far reaches of Britain and counters many of the negative perceptions of Scotland from that time.’

Heritage science connects people to their culture, linking everyday lives to the history, traditions and discoveries that form the basis of modern society. ‘For me, it’s all about storytelling,’ says Quye. ‘Understanding world cultures through artefacts of the past and saving them so that we can continue to enjoy these pieces of our history.’

Correction: This article was updated on 27 February 2023 to clarify who Quye worked with during her PhD.

1 Reader's comment