Scientists in the US have designed a hapten conjugate to inoculate against the harmful pharmacological effects of xylazine, a common animal tranquiliser that is increasingly mixed into street opioids.

Adding xylazine to opioids such as fentanyl and heroin prolongs their euphoric and sedative effects, stretching illicit drug supplies with a cheaper but potent ingredient. Xylazine also enhances opioids’ depressive effects on the respiratory and nervous system. And it’s nicknamed the ‘zombie drug’ because of the wounds that form on users’ bodies and refuse to heal. ‘You really have to see someone with these skin ulcers and who had to have a limb amputated, it is quite alarming to say the least,’ says Kim Janda from the Scripps Research Institute.

Last year, Anne Milgram, the administrator of the US Drug Enforcement Administration, said ‘xylazine is making the deadliest drug threat our country has ever faced, fentanyl, even deadlier,’ in a public safety alert on the agency’s website.

Fentanyl overdoses can be treated with the drug naloxone. ‘A simple way to think of it is that naloxone brushes fentanyl off the [µ-opioid] receptor,’ explains Janda. However, xylazine primarily stimulates α-2 adrenergic receptors and therefore naloxone has no effect. ‘[Xylazine’s] diverse and complex physiological processes involving the α-2 adrenergic receptors convolute the use of a simple receptor antagonist to target the central nervous system site of action.’

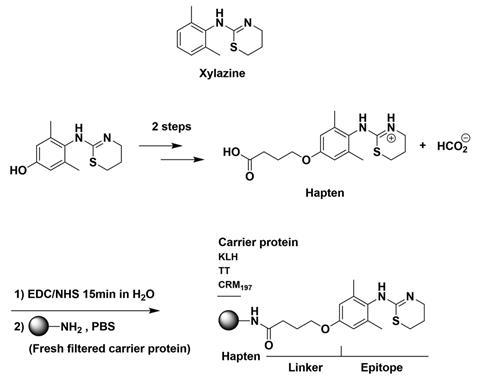

Janda’s group has pioneered using the immune system to target drug addiction, a concept known as immunopharmacotherapy. Typically, immunopharmacotherapy combines a small molecule, or hapten, that the immune system would not normally recognise, with a large protein the immune system does recognise to trigger it to generate antibodies against the small molecule.

Now, Janda’s team is exploring if immunopharmacotherapy will work for xylazine. They connected the para-position of xylazine’s dimethyl phenol amino ring, via a three-carbon spacer, to three different proteins that trigger an immune response – CRM197, a non-toxic mutant of the diphtheria toxin, keyhole limpet hemocyanin or tetanus toxoid. Given the synthetic chemistry to create the conjugate requires organic solvents, whereas proteins are prepared under aqueous conditions, linking the two components was not a trivial task.

They administered the xylazine-based conjugates to mice and monitored how the mice moved and breathed when they were later given xylazine. Rodents given the tetanus toxoid-based conjugate scored better for both parameters compared to controls, while those given the keyhole limpet hemocyanin-based conjugate experienced less respiratory depression.

Mark Smith, an expert on the behavioural effects of opioids at Davidson College in North Carolina, US, says the study ‘provides proof-of-concept that the immune system can be harnessed to reverse or prevent the harmful effects of xylazine, thus paving the way for the development of vaccines and their testing in human populations.’

References

M Lin et al, Chem. Commun., 2024, 60, 4711 (DOI: 10.1039/d4cc00883a)

![Chemical structure of Pillar[6]MaxQ](https://d2cbg94ubxgsnp.cloudfront.net/Pictures/380x253/6/2/1/523621_chempr1747_proof1_891632.jpg)

No comments yet