Vaccine experts often dislike this question on comparing jabs, and warn against simplistic head-to-head ‘vax-offs’. Having said that, Moderna could be seen as top on effectiveness against severe disease, followed by Pfizer–BioNTech, then Novavax, Janssen and Oxford–AstraZeneca. But some scientists note that in the real world all the vaccines are protecting similarly against severe disease. There is also debate about whether some vaccines give longer lasting protection than others.

What does the initial trial data tell us about the protection vaccines provide against the original virus and early variants?

Phase 3 trials of the two mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech achieved over 90% efficacy in late 2020. The Janssen viral vector vaccine reported a 67% reduction in the number of symptomatic Covid-19 cases with one jab, and the two dose Sputnik V vaccine reported a 91.7% drop. The Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine reported an over 70% reduction in symptomatic Covid-19 cases .

In September, the Novavax vaccine reported 87.7% protection against infection. The Sinopharm vaccine reported efficacy of 79% against symptomatic infection. A trial for SinoVac showed 51% efficacy against symptomatic infection.

These figures, however, are not directly comparable as different end points and measures of efficacy were used. The best way to compare vaccines would be head-to-head vaccine trials, but there’s little incentive for companies to conduct these.

Was vaccine effectiveness reduced in the delta variant?

Yes. A study of Pfizer–BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines found protection against symptomatic illness with delta fell to 47.3% and 69.7%, respectively, after more than 20 weeks. The decline was greater in those aged 65 and over.

Protection against symptomatic disease from the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine fell from 93.7% to 88%, and for AstraZeneca fell from 74.5% to 67% for delta, compared with the alpha variant. A comparison between Moderna, Pfizer–BioNTech and Janssen in September in the US reported effectiveness against hospitalisation at 93%, 88% and 71%, respectively.

Again, vaccines held up better in reducing hospitalisation – 77% for AstraZeneca and 93% for Pfizer–BioNTech 20 weeks or more after the jabs. This matches a New York study that reported robust protection against hospitalisation, but with effectiveness against infection declining from 91.8% to 75%. Qatar data similarly showed strong protection from vaccination against severe disease.

How do the vaccines perform when it comes to omicron?

New variants, especially omicron, dial down the protection against symptomatic infection offered by Covid-19 vaccines that are based on the ancestral strain. There is, however, a stark difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated in terms of severe disease. In the US, unvaccinated people are 13 times more likely to die from Covid-19.

Protection against developing symptomatic Covid-19 caused by omicron is significantly lower compared with the delta variant and wanes rapidly, recent UK data showed. The AstraZeneca vaccine offered no protection against symptomatic omicron infection 20 weeks after the second jab, whereas the effectiveness of Pfizer or Moderna jabs dropped from around 65% to around 10% 20 weeks after second shot.

Two to four weeks after a third or booster shot with Pfizer or Moderna given some months after the initial vaccine, protection from symptomatic infection ranged from 65% to 75%, dropping to 55% to 70% at five to nine weeks and 40% to 50% after 10 weeks.

That doesn’t sound impressive. What about severe disease?

The news is better. Protection against hospitalisation with omicron after a booster approaches 90% (78% to 93%) in UK data. One dose of vaccine was associated with a 35% reduced risk for hospitalisation among those sick with Covid-19; two doses reduced this risk by 67% up to 24 weeks after the second jab. We don’t yet know how long protection lasts after a booster jab.

How do antibody levels compare after different jabs?

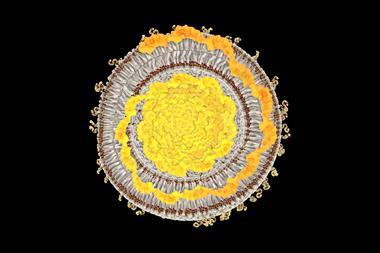

Neutralising antibodies target the spike protein and impede entry of the virus into our cells. The more neutralising antibodies the better, but they decline over time and even a single spike mutation can change its shape and interfere with antibody binding.

An earlier meta-analysis had noted the highest antibody levels for Moderna, followed by BioNTech–Pfizer, the Russian Sputnik V, Covaxin inactivated virus vaccine from Bharat Biotech, single-shot adenovirus serotype 26 vaccine and AstraZeneca. Antibody levels alone, however, do not decide clinical outcomes.

How much do antibody levels decline over time?

Quite a bit. Another approach measured neutralising antibodies against the virus, reporting high levels for Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna and lower levels for Janssen. Eight months later, levels were 34-fold lower for Pfizer–BioNTech and 44-fold lower for Moderna, but only a minimal decline for Janssen’s vaccine.

Do declining antibody levels matter?

Neutralising antibody levels remain the best proxy measure for vaccine performance. But you need far more to protect against an infection than against severe illness. This was illustrated by a prediction last summer that neutralising antibody levels would drop quite quickly over the first eight months after vaccination or infection, eroding protection against symptoms, but that levels six-fold lower would still protect against severe disease.

Recent UK data indicates that AstraZeneca offers little protection from illness as a result of omicron, with the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA jabs offering just 10% protection after 20 weeks.

Is it a surprise that vaccine efficacy falls?

For flu and endemic coronavirus infections, reinfection is possible one year later, though usually a second illness is mild. Previous research showed that protection from flu declined by about 7% each month.

Vaccine effectiveness against severe Covid-19 appears to decrease by about 8% over six months in all age groups and 32% against symptomatic disease, according to the World Health Organization. Older people and people with underlying illnesses typically start off with lower antibody levels after vaccination, and are therefore more prone to infection.

Immunologists hope future Covid-19 vaccines will offer longer-lasting protection. Some vaccines protect for far longer – the mumps vaccine offers immunity for 27 years.

What does lab research reveal about omicron?

Lab studies have predicted future variants and suggested one with 20 spike mutations would evade antibodies raised by an mRNA vaccine. Omicron then surprised virologists by sporting 30 spike mutations, including at least 15 in the part that binds to our cells. There were early indications from South Africa that it was better at reinfecting people, and modelling suggests that immune evasion could be a major driver of its rapid transmission. Lab studies show around a 40-fold reduction in binding to omicron by existing neutralising antibodies.

What does this mean for vaccines?

A recent lab study revealed that two shots of mRNA vaccine gave low but detectable antibody neutralising activity against omicron. A booster shot restored antibody levels somewhat. The study also showed the benefit of vaccination in those who had recovered from Covid-19. A study also shows that a third mRNA shot in vaccinated or recovered adults pepped up antibody activity.

Another study revealed an big reduction in neutralising antibodies against omicron, compared with the ancestral virus for those vaccinated with Pfizer–BioNTech, and no detectable neutralisation against omicron in those vaccinated with the Sinovac vaccine, even with a prior infection. Those with two Sinovac jabs may require two additional boosters with an mRNA vaccine against omicron, this study concluded.

How effective are boosters?

We already knew a second shot for mRNA vaccines is needed for good immunity, especially in the elderly. A booster shot preserves efficacy of nearly 90% for severe disease, ramping up neutralising antibodies by 20- to 40-fold. It is estimated that without a third jab, effectiveness against asymptomatic infection is about 30% rather than about 70%.

Protection against severe disease from two jabs drops to around 70% after three months and to 50% after six months. But a booster jab offers 90% protection against hospitalisation among those aged over 65 years even after three months. Protection against mild illness from a third jab drops to around 30% by three months.

A fourth Pfizer-BioNTech jab reportedly boosted antibodies five-fold after one week, according to an Israeli report. The European Medicines Agency remains undecided on the value of a fourth jab at this stage.

What about T cells?

CD8 ‘killer’ T cells terminate infected cells by recognising viral protein fragments displayed on a cell’s surface. Some proteins, such as the internal machinery of the virus involved in its replication, are less liable to mutate than the spike because it is essential they retain the same structure to perform their roles. T cells are, therefore, crucial for targeting viruses already inside cells, in contrast to antibodies which attach to the surface of viruses before they infect cells. Immunologists say it is difficult to calculate the contribution of T cells to protection, but antibodies made by B cells are not the only game in town.

In 2020, macaques were protected from Sars-CoV-2 after receiving serum with antibodies from convalescent macaques, but only if the serum contained enough killer T cells. Multiple studies now point to vaccine-induced T cells targeting omicron. A recent study found that T cells’ response to the virus, especially after mRNA vaccination, remained intact against omicron.

What are the unknowns though?

We still don’t know what T cell or antibody levels are enough to provide protection. T cells are generally long lived – they have been detected 17 years after Sars infection – but antibodies wane and drop below protective levels. We don’t know yet if antibody levels will decline more slowly after a booster.

Are we going to need boosters forever, as some vaccine company chief executives hinted?

Not necessarily. The immune response is dynamic and antibody titres alone do not determine our response to infection. Some hope a booster will prep enough T cells to ward off serious illness for longer.

But new variants introduce uncertainty. Some vaccine companies are developing an omicron-specific vaccine, with Pfizer promising one by March, and there are projects looking to develop vaccines against all Sars-like viruses. Certainly, better vaccines are needed. What future variants will mean for the effectiveness of vaccine protection is unknown.

Is there any good news?

The number of people infected with omicron will give populations as a whole better protection against Covid-19. Also, countries such as Portugal with high vaccination rates have shown a rapid spike in infections, but only a small rise in hospitalisations. More vaccines are on the way too – Novavax recently got the green light in the EU. Mixing vaccine types may also offer some additional gains in protection.

Thanks to Leo Swadling, immunologist at University College London (UCL), and Danny Altmann, immunologist at Imperial College London

No comments yet