Although aqueous hypochlorites have been used for centuries as bleaching agents, scientists in Canada have now for the first time characterised them using x-ray crystallography. ‘[This is] a really big omission, something that simply got forgotten in chemistry,’ says research leader Tomislav Friščić from McGill University.

The first known synthesis of aqueous chlorine for bleaching comes from the 18th century as French chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet created Eau de Javel, named after the Parisian district where he ran a chemical factory. Nearly a century later Antoine Germain Labarraque, another French chemist, made a disinfectant using sodium hypochlorite, calling it Eau de Labarraque. Today, more than 9 billion litres of aqueous sodium hypochlorite are manufactured annually for this use.

But Friščić realised there was no record of the crystal structures of hypochlorite, ClO–, or hypobromite, BrO–. ‘I’m still in disbelief,’ he says.

Friščić’s work is usually in mechanochemistry but he came across solid sodium hypochlorite when researching different solvent-free reactions. He explains that he ‘had no idea that the thing could be isolated in the solid state, and not to mentioned it’s apparently commercially available.’ The first solid hypochlorite crystal, NaOCl·5H2O, was synthesised in 1898.

The team looked for a hypochlorite crystal structure only to find ‘there was absolutely nothing, zilch’, Friščić explains. But they found some reports of the unit cell, including one of calcium hypochlorite published by the Armenian Chemical Society in the 1960s. ‘Luckily, it was written in Russian because I can read Russian, I can’t read Armenian,’ Friščić recalls.

Friščić believes others might have simply assumed that the crystal structure of such common compounds was already known, meaning they were never characterised. So Friščić and his group decided to try themselves, describing it as ‘a labour of love’.

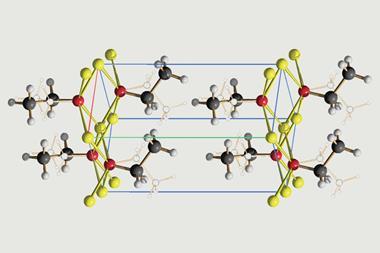

Sodium hypochlorite crystals, which are commercially available, were characterised along with sodium hypobromite synthesised in the lab. Friščić describes them as ‘really pretty small yellow crystals’. Handling them at room temperature was the main challenge. ‘[They] were just about stable enough that you could pull them out at liquid nitrogen temperatures, mount them on a single crystal diffractometer and determine the structure,’ Friščić explains.

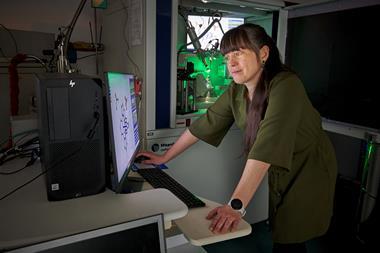

Christine Beavers, an x-ray crystallographer at the UK’s Diamond Light Source says that hypohalites are ‘the kind of things you learn in first year chemistry, I thought they were all pretty done and dusted’. Beavers explains that the procedure was ‘very standard crystallography, the most difficult thing was that the crystals seem to dissolve in themselves’. She was especially surprised this had not been done before.

‘I’m not saying that this is going to create a better bleach’ Friščić says. But he hopes to use hypochlorite and hypobromites as building blocks for new materials.

References

F Topic et al, Angew, Chem. Int. Ed., 2021, (DOI: 10.1002/anie.202108843)

No comments yet