A computational study has challenged the long-standing notion that electrocyclic reactions can be neatly divided into being either ‘allowed’ or ‘forbidden’.1 ‘The energy difference between allowed and forbidden alternatives can sometimes be very small indeed,’ says Barry Carpenter, from Cardiff University in the UK. ‘In the smallest case that I found, it was less than half the barrier to the internal rotation of ethane.’

In electrocyclic reactions, a type of pericyclic reaction, one π bond and one σ bond interconvert via a cyclic transition state. The Woodward–Hoffman rules, developed in 1965 by Robert Burns Woodward and Roald Hoffmann, predict the favourability and stereochemistry of a pericyclic mechanism. Based on orbital interactions, the rules class reactions as being either ‘allowed’ or ‘forbidden’.

To investigate how distinct these two classifications are, Carpenter used n-electron valence state perturbation theory (NEVPT2) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations to analyse the energy differences between the ‘allowed’ and ‘forbidden’ reactions for a range of electrocyclic reactions: predominantly cyclobutene ring openings and (Z)-1,3,5-hexatriene ring closures, including their benzannelated analogues.

In Carpenter’s calculations, the energy difference between so-called ‘forbidden’ and ‘allowed’ reactions ranged in value from 29.3 to 1.4 kcal/mol, with some being comparable in size to other factors that affect reaction barriers, like steric interactions.

‘The [previous] classification of pericyclic reactions was simply binary,’ explains Carpenter. ‘That turns out to be misleading, because really, rather than being allowed and forbidden, they are favoured and disfavoured, and sometimes the difference between the favoured option and the disfavoured option is energetically quite small. He advocates for replacing the terms ‘allowed’ and ‘forbidden’, with ‘Woodward–Hoffmann favoured’ and ‘Woodward–Hoffmann disfavoured’.

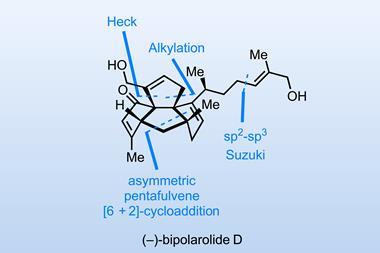

As an example of when the Woodward–Hoffman rules can fail, Carpenter highlights a synthetic route proposed 30 years ago to the aureolic acid class of anticancer compounds.2 The chemists behind the route had employed the Woodward–Hoffman rules to predict their products, but Carpenter details how other molecular factors would lead to an unexpected result. ‘Had they actually done those reactions, they would have had a nasty surprise because they would have come out with the wrong stereochemistry,’ he says.

The finding reinforces the need for a nuanced approach to reaction planning. ‘If a user employs the Woodward–Hoffman rules in their binary fashion, they might expect a reaction to come out one way, when in fact it will come out another way, because factors other than the Woodward–Hoffman rules might outweigh the Woodward–Hoffman rules and cause the reaction to follow the nominally forbidden pathway,’ explains Carpenter.

‘Allowed-ness and forbidden-ness are too much complexity packed into two words,’ says Judy Wu, a computational chemist at the University of Houston in the US. ‘[This work] reminds us that figuring out whether an electrocyclic reaction occurs isn’t simple – it is a complex problem, which is surely influenced by orbital symmetry rules, but by other factors, too. Steric effects, ring strain, dynamic effects and many other effects, can all have real energetic consequences on the reaction barriers of electrocyclic reactions. It’ll certainly change how I approach this topic in my advanced organic chemistry class.’

Carpenter believes that as technology continues to advance, models and theories will continue to be refined. ‘Science is really a process of model building and models get refined with time as we get new information and new capabilities,’ he says. ‘Models can only be as sophisticated as the technology available at the time that they were invented.’

Knowing this, he accepts that ‘in some future generation people will look at the stuff that I’ve done and say, well, that was pathetic, because that’s the way science works.’

References

1 B K Carpenter, Chem. Sci., 2025, DOI: 10.1039/d4sc08748h

2 D N Hickman et al, Tetrahedron, 1996, 52, 2235 (DOI: 10.1016/0040-4020(95)01054-8)

No comments yet