Low protection rates in trials and uncertainty over cost-effectiveness leave vaccine’s future up in the air

After decades of research, a malaria vaccine has finally been given the green light by a regulatory agency. But with limited efficacy and questions over the vaccine’s cost, its future remains unclear.

The new vaccine, Mosquirix or RTS, S, is intended for use in babies and toddlers. Developed by a team led by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), it targets the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, recognised as the leading cause of malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa where the disease kills around 1300 children every day. No approved vaccines currently exist for malaria.

The European Medicines Agency gave the vaccine a ‘positive scientific opinion’ after considering its quality, safety, efficacy and risk–benefit profile. The World Health Organization (WHO) will now provide recommendations by November that will consider additional factors, including implementation, affordability and cost-effectiveness.

Mosquirix works by triggering the body’s immune system to defend against the parasite when it first enters its human host’s bloodstream, as well as when the parasite infects the liver. It is designed to prevent the parasite from infecting, maturing and multiplying in the liver, from where it re-enters the bloodstream and infects red blood cells, resulting in malaria.

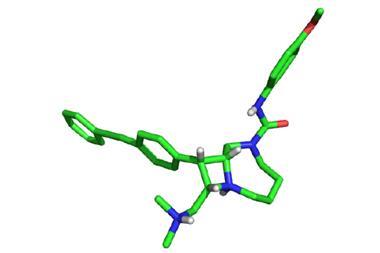

The vaccine has a P. falciparum protein that is secreted during the parasite’s sporozoite stage – the cell responsible for infection of the host – fused with a hepatitis B surface antigen (RTS) and combined with another hepatitis B surface antigen (S). The three form virus-like particles when produced by recombinant DNA technology. Because of the way it’s made, the vaccine also protects against hepatitis B.

Limited protection

The principal evidence for Mosquirix’s efficacy was published earlier this year. A large clinical trial was conducted in seven African countries involving 15,459 infants (6–12 weeks old) and children (5–17 months old). Participants were vaccinated three times with some receiving a booster 18 months later.

The vaccine was found to work better against clinical and severe malaria in children than in infants, but waned over time in both groups. However, protection was prolonged by the booster.

32% of children who received four doses of Mosquirix were protected from severe malaria. Importantly, without the fourth booster dose, there was no significant protection against severe malaria in this age group. In infants who received four doses, the vaccine reduced the risk of clinical episodes of malaria by 31% in the first year and by 26% over three years. There was, however, no significant protection from severe malaria.

‘Despite the falling efficacy over time, there is still a clear benefit,’ says study author Brian Greenwood, professor of clinical tropical medicine at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK. ‘Given that there were an estimated 198 million malaria cases in 2013, this level of efficacy potentially translates into millions of cases of malaria in children being prevented.’ Greenwood acknowledges that RTS,S is ‘imperfect’, but says it can still play a role in controlling the disease.

Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute at Oxford University, UK, says this is an important first step. ‘The results in toddlers given four doses provides the best chance so far. But at present children are not vaccinated four times. It would involve new immunisation time-points as, currently, babies are immunised against a range of diseases at two, three and four months of age.’ He says trying to introduce new vaccination time-points could be a real ‘headache’.

Efficacy is another issue. Hill explains that the body needs particularly high levels of antibodies to fight malaria compared with other diseases: hundreds of micrograms of antibodies per millilitre of blood compared to one or two in meningitis, for example. And these levels fall quickly, so while some protection is possible during the first year, antibody levels drop dramatically after that.

Rebound danger

Hill also brings up the problem of ‘rebound’. The trial found that if the children were not vaccinated for the fourth time, they were more likely to develop malaria than the controls. ‘It appears that the vaccine is damaging any naturally acquired immunity that may develop,’ he says. Natural immunity is against the blood-stage of infection and because the vaccine can prevent this stage occurring so often, natural immunity may be reduced.

So who would pay for Mosquirix if it gets licensed? David Kaslow is vice-president of product development with the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, which co-funded the study. He points out that public–private partnership Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has said there would be a reasonable case to support the vaccine, if the WHO recommends it. Kaslow also notes that GSK has committed to a not-for-profit price for the vaccine that would cover the cost of manufacturing, along with a small return of around 5% that will be re-invested in R&D for second-generation malaria vaccines or other neglected tropical diseases.

Health economists are speculating that a course of four doses would cost about $20 (£13). However, Hill says taking this vaccine forward will be challenging and big questions remain about its cost-effectiveness. ‘Nobody is sure if it will happen or who will pay,’ he says. ‘Bed [mosquito] nets are more effective and using more of these would probably cost a fraction of the amount.’

No comments yet