The brightly coloured fabric covers of Victorian-era books contain dyes that have potentially dangerous levels of lead and chromium, chemists at Lipscomb University, US have discovered. As a result, precautions have been put in place to keep librarians and visitors at the university safe. All 26 books studied have been pulled from circulation and sealed, and they have instructed the librarians on campus to handle these items with gloves and use heavy-duty masks if working in a confined space. The Lipscomb team estimates that there are roughly 50 to 100 books in the university’s library that need to be tested and potentially removed from circulation. Their work was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society in Denver.

The chemists identified that a number of pigments in the attractive jackets of these books contained poisonous metals and that their concentrations were above legal US limits for chronic exposure. For example, one of them had more than twice the safe level of lead and in another case the chromium was almost six times the limit.

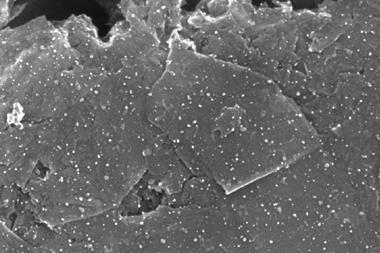

Tests revealed that approximately seven of the 26 books analysed contained elevated levels of lead and chromium that exceeded the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) toxicology and workplace guidelines. The most hazardous sample contained an average of 238ppm lead and 52ppm chromium. If roughly 10% of that book cover flaked off and the pigments became aerosolised, it could pose an acute toxicity risk. Such potentially dangerous conditions could arise, for instance, if a librarian or book collector inhaled these particulates for over half an hour, they note. ‘This poses a potential serious threat to anyone in close proximity during a normal work shift,’ says undergraduate Leila Ais, who is working on the research along with fellow undergraduate Abigail Hoermann and recent graduate Jafer Aljorani.

The study was sparked by the Poison Book Project, an interdisciplinary research initiative at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Delaware and the University of Delaware exploring the materials Victorian-era bindings were made from. After two Lipscomb librarians took an interest in the Poison Book Project and were curious about their own university’s books from the ‘Gilded Age’, they approached the chemistry department a couple of years ago.

Beyond books

‘We got a positive result of elevated chromium and lead right away, so that lent to a lot of excitement and we began testing more books,’ assistant chemistry professor Joseph Weinstein-Webb recalls. ‘I didn’t jump into this for a fascination of books … I am more of an optics and spectroscopy person … interested in using different incident beams, different emissions, to get a signal of elements and looking at detection.’

The researchers still need to double and triple check some measurements on those 26 books, so they do not anticipate publishing their results until 2025. The team now wants to extend its survey to local libraries and book collectors, as well as to explore using portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF) to establish a standardised analytical protocol to test potentially toxic book covers.

The Lipscomb group is particularly excited about the potential of pXRF because it is fast, cost-effective, compatible with heavy metals, provides data in a matter of seconds and, most importantly, is non-destructive.

Another goal of the researchers is to establish safer handling guidelines for these books. They are already partnering with librarians at local universities who are considering handing over books from that era for testing. Weinstein-Webb is optimistic that this is doable. ‘Because it is literally a minute per scan we can go through many samples quickly,’ he says.

Beyond books, Weinstein-Webb also wants to test ceramic and other materials for heavy metals that may have been introduced during production. Currently, he is discussing a partnership with Lipscomb’s archaeological department, in collaboration with universities in Israel, to test artefacts.

No comments yet