Tea tree oil is under threat of being banned in the UK and EU after assessments by regulators have found that it is toxic to reproduction. Industry representatives are challenging the proposals, claiming the animal data showing tea tree oil’s health effects does not apply to humans.

With its distinct fragrance and antimicrobial properties, the essential oil extracted from the leaves of the Australian tea tree, Melaleuca alternifolia, is used in a range of cosmetic products, traditional medicines, and as a natural fungicide for crops such as grapes and coffee.

Classification as reprotoxic category 1B (presumed human reproductive toxicant), as proposed by the British Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in August, would result in a default ban in cosmetics and pesticides. The HSE’s conclusion is based on data collected by its EU equivalent, the European Chemicals Agency (Echa), whose risk assessment committee (RAC) adopted an opinion last November to classify tea tree oil as a category 1B reproductive toxicant under the EU classification, labelling and packaging (CLP) regulation.

Both classifications are primarily based on studies that involved force-feeding tea tree oil to rats, rabbits and dogs. They showed adverse effects on male reproductive systems, including sperm formation, with the strongest effects in rats.

Industry representatives say the data is inappropriate for evaluating potential human impacts, because the effects shown are species-specific. In the studies, rabbits recovered once dosing was complete; rats and dogs did not. ‘Rats are not a good model for human reproductive fertility studies. [They] can’t metabolise terpenes like humans can,’ says Lauren Hamilton, chief executive of the Australian Tea Tree Industry Association (Attia).

Defenders also question whether the force-feeding process is appropriate for identifying risks in humans, who use tea tree oil topically, and at much lower doses.

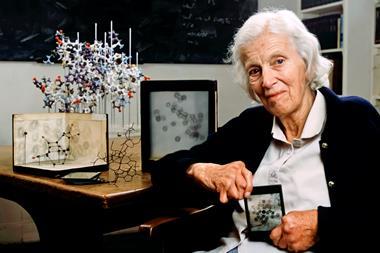

‘From the evidence that I’ve seen, I have very few concerns that there are human safety issues with the reasonable use of tea tree oil,’ says Christine Carson, a microbiologist without industry affiliation who studied tea tree oil at the University of Western Australia for 20 years. ‘It’s hard to reconcile this data with what we’re seeing in humans.’

The RAC and HSE commonly use animal data to assess toxicity effects in humans, however, and the studies in themselves are solid, says Geraldine Garrs, an independent cosmetics safety assessor.

‘I would absolutely trust that set of data,’ Garrs says, but adds that an automatic ban on the oil would be a shame. ‘Reprotoxicity is highly impactful, so you don’t want to take any chances. But we’ve been using tea tree oil under a safe dose rule for a long time, and if the industry wanted to defend that, I would support it.’

Echa said the RAC considered whether there were any reasons that would support a different classification outcome, but the evidence on mode of action and human relevance considerations ‘was not sufficient’.

New data in progress

In the UK, the HSE technical report is only the first step of the classification process, and companies have another year to submit data to defend the substance.

The recommended EU classification will become law when the CLP is updated through an ‘adaptation to technical progress (ATP)’, which is issued yearly by the European Commission.

Attia has asked the authorities to delay the next ATP update while it gathers data to dispute the classification. The trade body has commissioned contract research organisation Charles River Labs to carry out cell line tests in rats, humans and rabbits, which it hopes will show that tea tree oil has a different mode of action in humans.

Knock-on effects

Garrs and Carson think it’s unlikely that industry will overturn the classification proposals. ‘But at least new data might help to get other essential oils assessed differently,’ Carson said.

She and Attia share concerns that the classification will have a knock-on effect on other essential oils, which share many of the constituents that may be implicated in tea tree oil’s reprotoxic effects. p-Cymene, a monoterpene derivative found in many essential oils, is currently being evaluated for reprotoxic properties under the EU CLP regulations.

‘This isn’t a question of doing more tests until the desired results are achieved. [The industry is] genuinely trying to understand what tests are relevant and what the data mean. And this quibbling over the data is not going to be unique to tea tree oil,’ Carson says.

No comments yet