How are chemicals stored in bulk?

When you open up a chemical cabinet in your laboratory, what do you see? More often than not, you see the chemical that you want at that moment, surrounded by others that might be useful, but not at that moment – a litany of chemicals in their packaging. But while the chemicals themselves present a huge variety of experimental possibilities, their containers are more mundane, being mostly a variation on a single theme: glass bottles with a screw top lid, with a smattering of plastic bottles.

Now imagine yourself in the doorway of a chemical warehouse, opening the roll-up door. What would you see? In our warehouse, you’d see a wide variety of containers, but the most obvious one is practically the symbol of our industry – the trusty 55 gallon (or 200 litre) drum. There are so many different varieties of them, but they all seem to come in groups of four, bound in plastic together, and strapped to a wooden or plastic pallet so that a forklift or a pallet jack can lift them easily. Most of these drums are steel, with two or three ‘chimes’ – protruding rings around the drum – that are for strength. The drum is often lined with an epoxy-phenolic or a HDPE coating to protect the steel from corrosion.

For liquids, a typical 200 litre drum has one or two openings, or ‘bungs’. These are typically 10 centimetres or so in diameter, and are removed with a bung wrench, which is definitely not a tool that you would find in a chemical laboratory. It fits into the fittings in the bung and unscrews. It’s amusing to learn all the different kinds of bungs that you can find in the industry – there is always a new one, and it always seems to come on the drum that needs to be opened urgently.

Solid chemicals tend to come in open-top drums, where the entire lid can be removed. Inside is typically a large bag that can hold the product, often in 25 or 30 kilogram quantities. The bag often has an additional bag on the outside, and both are sealed together with a cable tie of some sort. That isn’t always the case, though – like chemists, bulk chemicals are a global affair, and you’ll find all sorts of different packaging from around the world.

If you come back to a discoloured solution and little pieces floating about, that’s a sign that you should not be using this material to store your chemical

One day in a former kilo scale laboratory workplace, a co-worker opened the first of many open-top drums. In it, he found what he thought was a bag inside another bag. However, when he lifted this up, he discovered that it wasn’t a sealed bag at all. Instead, the 25 or 30 kilograms of raw material were wrapped up in plastic wrap as if it were an enormous candy wrapper, with the bottom end tied shut. Needless to say, he wasn’t very pleased with this, nor with the fact that we had another 50 or so of these containers to open and use, with the concern of the product leaking out of the bottom of each bag.

One of the classic concerns with storing chemicals, especially for a long period of time, is the compatibility of the storage material. Worried about your new acid chloride eating away at the drum? Put a pre-weighed piece of your storage material (often called a coupon) in a container of the material and leave it overnight. If you come back to a discoloured solution and little pieces floating about, that’s a sign that you should not be using this material to store your chemical. If you want to be especially careful, you’ll take your pre-weighed coupon, wash it off, dry it and weigh it to make sure that it hasn’t lost any weight. If it passes that test, congratulations – you have something that will probably make a safe storage material.

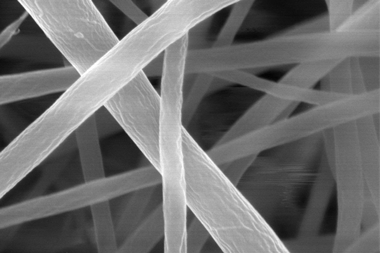

My favourite bag that I didn’t know existed until I worked in chemical manufacturing is what’s called the supersack. These enormous bags don’t really look like the 25 kilogram paper sacks that you might see storing flour – rather, they are large white polypropylene bags that look like a large hammock when they’re not holding material, and like a mattress or a bean bag for a gigantic child when filled. They often carry as much as 500 or 1000 kilograms of bulk or commodity materials that aren’t particularly aggressive to packaging, like urea or high molecular weight polymers. Often, I see these supersacks being carried around by freight trucks or being offloaded at harbours. They’re not glass bottles in cabinets, but like them, they’re doing their job, day and night, keeping chemicals safe and packaged while being transported around the world.

No comments yet