Derek Lowe lays out how the trials work, and why they get paused and restarted

The coronavirus pandemic is continuing to provide opportunities for people to learn about clinical research; I will say that for it. The latest is in the way the vaccine clinical trials have been going. Many people had been wondering when the first readout of data might be for these (although this was more likely expressed as: ‘When are we going to know if this thing actually works?’). They were likely not pleased to hear the answer: ‘We’re not sure’. But that is the real answer in such trials – they are not set to provide data at a set time, but rather after a set number of cases.

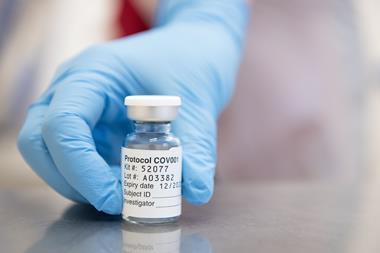

A large population is going to have some serious adverse events, no matter what. The key question is whether they’re linked to the vaccination

It’s all a statistical problem, naturally, because clinical research is (first, middle, and last) about the statistics. In this case, you have to look at the number of participants in the treatment and control arms, and figure how many coronavirus cases have to happen in order to give you an answer of the form: ‘this vaccine so far appears to be at least X% effective, within these pre-defined error bounds’. It’s then a matter of waiting for that number of cases to occur before the monitoring committee unblinds the numbers to see how things went.

For a while, there were worries about possibly not having enough coronavirus cases in the test populations to get those statistics in a timely way. Unfortunately, we have moved well beyond such concerns in much of the northern hemisphere. In fact, it looks like both Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna are ending up with more cases than expected at their first readouts, since the number of cases in their trials has increased so rapidly in such a short period. This is very likely the case with the other trials as well. It’s a horrible way to end up with better statistics, but here we are.

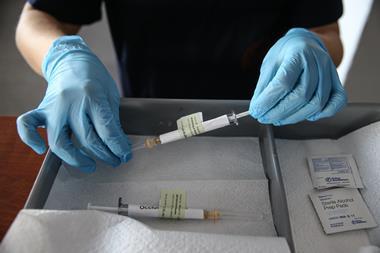

The safety readout for the trials has its own features, since serious adverse events are expected to be both rare and idiosyncratic. A vital feature of the human adaptive immune system is that everyone’s suite of defenses is slightly different, with variations that are both innate and accumulated through exposure to different pathogens (as retained in memory B and T cells). As the number of different autoimmune disorders shows, there are a great many ways things can go wrong and very few ways to predict when that might happen. So for a vaccine trial, you need as large a sample size as you can get and a great deal of watchful waiting. You’re in the rare position of preparing to administer a new therapy to a huge number of people who aren’t even sick yet, so safety is critical.

Despite the twists and turns, these trials are really going as well as anyone could have possibly expected

We’ve already seen several trials halt due to some form of serious event. The important thing to remember is that a large population is going to have some of those, no matter what. The key question is whether the trouble is linked to the vaccination. Was the affected patient even in the treatment group? Does the adverse event look like something that is known to be caused by immune dysfunction? And does the medical history of the patient offer any clues? A cardiac issue in an older, overweight patient could easily be entirely unrelated to the vaccine, but sudden neuromuscular problems in a younger female patient would set off alarms. One might immediately suspect something like Guillain-Barré syndrome, a known immune dysfunction. It can be brought on by infection (or sometimes by vaccination) and young women are the group most at risk. That would be a very concerning sign indeed.

Every clinical trial for every sort of drug has the possibility for the unexpected, and if you’re not holding your breath when the first human doses start then you haven’t been doing this work long enough. So far, none of the vaccine halts have been show-stoppers, and the first readouts of efficacy actually look very promising. Despite the twists and turns, these trials are really going as well as anyone could have possibly expected. There are still data to collect, pages to turn, outcomes to unblind. But if anyone had been able to offer the current results to me as a guarantee a few months ago, I would have immediately accepted!

1 Reader's comment