ChemRxiv could be a golden opportunity if we embrace it

In case you hadn’t noticed, ChemRxiv is open for business. The preprint server, managed by the American Chemical Society (ACS), and supported by the Royal Society of Chemistry, the German Chemical Society and others, will now host a preprint of your paper for general consumption.

But beware: not all journals are happy about it, even within the ACS. The Journal of the American Chemical Society, for example, warns that any content of a submitted paper that has been made publicly available, in this or other ways, ‘may jeopardise the originality of the submission and may preclude consideration for publication’. However, 80% of ACS journals do allow preprints, while others are still formalising their policies to permit them.

This reflects the diversity of views among chemists – some of who are ACS journal editors – about the pros and cons of preprint servers. One might have thought that the highly successful operation of the system that started it all 25 years ago, the arXiv for physics papers, would have settled that debate long ago. But different disciplines have different traditions and priorities to balance, so some debate is natural. The life sciences, for example, with commercial interests often at stake and a more proprietorial mindset, resisted following suit until bioRxiv began in 2013. Why chemists should be so hesitant is less obvious – although few scientific communities have quite the same degree of informal exchange and debate that characterises high-energy and particle physics, from which subdiscipline much of the impetus for the arXiv came.

This reflects the diversity of views among chemists – some of who are ACS journal editors – about the pros and cons of preprint servers. One might have thought that the highly successful operation of the system that started it all 25 years ago, the arXiv [https://arxiv.org/] for physics papers, would have settled that debate long ago. But different disciplines have different traditions and priorities to balance, so some debate is natural. The life sciences, for example, with commercial interests often at stake and a more proprietorial mindset, resisted following suit until bioRxiv [https://www.biorxiv.org/] began in 2013. Why chemists should be so hesitant is less obvious – although few scientific communities have quite the same degree of informal exchange and debate that characterises high-energy and particle physics, from which subdiscipline much of the impetus for the arXiv came.

Fuzzy submissions

So how’s it going, ChemRxiv? Pretty well, according to its publishing manager Marshall Brennan. In the first 10 weeks there have been 165 submissions, compared with around 550 for the entire first year of bioRxiv. ‘Even if our current submission rates remain flat, we should exceed expectations,’ Brennan says – though actually this rate is still rising.

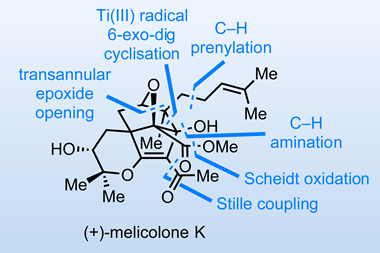

Already, the issue of what counts as publication priority has reared its head. Ryan Shenvi, of the Scripps Research Institute, US, and his colleagues posted to ChemRxiv their synthesis of the plant metabolite salvinorin A (a potential painkiller), and the paper has been the most popular so far, boasting 1500 downloads at the last count. But a month later, researchers at the University of Kansas, US, published similar work in Organic Letters.1 Did they rush it into print after seeing Shenvi’s preprint? Some have suspected so, but it’s possible that the paper was going to appear around then anyway – and as Brennan says, ‘having the preprint available made sure that Ryan’s contributions were still part of the conversation.’

Already, the issue of what counts as publication priority has reared its head. Ryan Shenvi, of the Scripps Research Institute, US, and his colleagues posted to ChemRxiv their synthesis of the plant metabolite salvinorin A (a potential painkiller), and the paper has been the most popular so far, boasting 1500 downloads at the last count. But a month later, researchers at the University of Kansas, US, published similar work in Organic Letters (A. M. Sherwood et al., Org. Lett. 19, 5414 (2017)). Did they rush it into print after seeing Shenvi’s preprint? Some have suspected so, but it’s possible that the paper was going to appear around then anyway – and as Brennan says, ‘having the preprint available made sure that Ryan’s contributions were still part of the conversation.’

That, frankly, is the real point: not who was first (which sadly still matters to the researchers concerned) but that by making such work publicly available, the scientific discussion can be broadened and enriched. That preprints render priority a fuzzy matter is a good thing, revealing what an artificial construct it always was.

It’s all the fuzzier because ChemRxiv doesn’t yet show exact submission times (there are plans to add them) – and also because the manuscript processing is done largely manually. In one case, this meant that the operational pause over the weekend resulted in two submissions in a hotly competitive area being posted three days apart, because one arrived just before the late Friday cutoff and the other just after. ‘We’re working on better automating our processes to completely avoid the issue in the future,’ says Brennan.

Disciplinary approaches

It’s perhaps because of a legacy of priority races that organic chemists are apparently proving cautious about using ChemRxiv. On the other hand, I suspect that the interdisciplinary nature of materials science, as well as its overlap with the bustling condensed-matter branch of the arXiv, explains why materials chemistry is currently the most active area for submissions. Together with theoretical and physical chemists, who may well also have prior experience with arXiv, these fields make up around 45% of ChemRxiv submissions. It’s conceivable that these early adopters, already relaxed with preprint culture, will help to persuade other chemists that there’s nothing to fear – and plenty to gain.

In particular, there’s the potential for sharing raw data. ‘ChemRxiv is built to handle datasets even better than manuscript files,’ says Brennan. ‘If you have an .xyz file from a computational output or a .cif file from a crystallographic study, not only can you make that file available, you can view and interact with it right in the browser without any additional software.’ He hopes to expand this support for rich data to techniques like NMR and HPLC. Again, science can only benefit from that.

As for whether there will eventually be unanimous acceptance of preprint servers by journals, Brennan says he hopes so – but that ChemRxiv respects editors’ rights to make their own decisions. Ultimately, the position should reflect that of the chemistry community as a whole, he says – so if you want a journal to become preprint-friendly, you ‘should write to the editors and let them know!’

References

1 A. M. Sherwood et al., Org. Lett., 2017, 19, 5414 (DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02684)

No comments yet