Meera Senthilingam

This week, Helen Scales questions a famous piece of French cuisine.

Helen Scales

If you’ve ever been tempted to eat frogs’ legs here’s a story that might make you think again. In Nigeria in 1869, a group of French troops visited their physician, Dr J. Meynier, suffering from the same symptoms. Their stomachs ached, their mouths were dry, and they all felt weak and nauseous. Meynier might have had trouble diagnosing their condition based on these symptoms alone until his patients admitted to one further problem: they were all suffering from persistent erections. This was long before the invention of Viagra but there was another potential culprit.

Spanish fly is one of the oldest, most legendary aphrodisiacs. It’s made from the crushed bodies of insects, which oddly enough aren’t flies and don’t come from Spain but are beetles in the family Meloidae, called blister beetles that live worldwide. The French soldiers denied using Spanish fly but did admit to supplementing their military rations eating frogs from a local stream. Was there a link between frogs and Spanish fly? The smart doctor went to the water’s edge and found frogs busily devouring a swarm of emerald coloured beetles. He surmised that whatever noxious substance is found inside these ’Spanish flies’ also hung around inside the frogs giving the troops more than they bargained for.

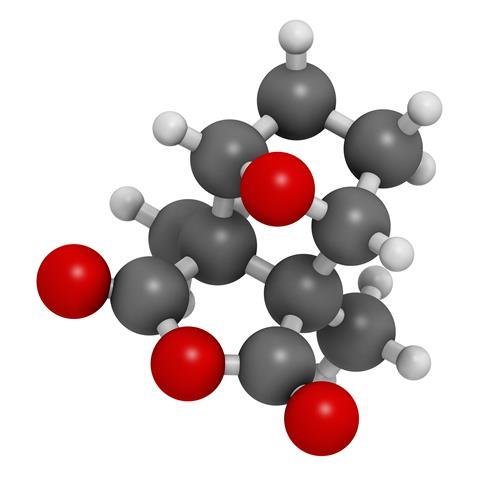

The active ingredient in Spanish fly is a bicyclic terpenoid called cantharidin, an odourless, colourless solid at room temperature. Its effects on the human body have been known for millennia. The ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates, prescribed ground blister beetles as a treatment for dropsy. Traditional Chinese medicine uses blister beetle to treat piles, ulcers, and rabies. Whether any of these treatments actually work remains unclear. But there’s no doubt that Spanish fly is powerful stuff. Let a blister beetle scuttle across your hand and you better hope it’s in a good mood. When angry or alarmed, they emit cantharidin drops that will bring you out in blisters.

Cantharidin is absorbed by lipid layers in the skin’s epidermis, disrupting transmembrane proteins that hold cells together resulting in blistering and lesions. Since the 1950s it’s been used to treat warts and another viral skin condition called molluscum contagiosum but only under strict medical supervision. Don’t go rubbing yourself with beetles.

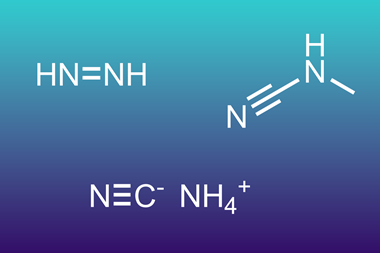

More dangerous is the effect of eating blister beetles. When consumed, cantharidin inflames the gastrointestinal tract and, depending on the dose, can completely strip away the stomach lining. As the kidneys try to purge the toxin from the blood it causes swelling in the urinary tract in what can appear to be arousal but is far from it: swallow two or three blister beetles and they could kill you. Cantharidin is about as toxic as cyanide and strychnine and there’s no known antidote. Notorious French aristocrat, the Marquis de Sade, got in trouble for giving prostitutes a box of chocolates laced with Spanish fly. The women survived but de Sade was sentenced to death for attempted murder.

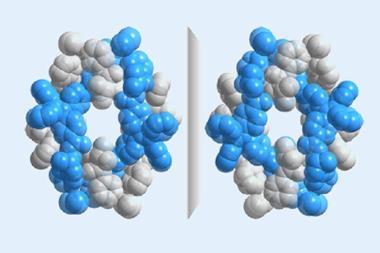

For beetles, on the other hand, cantharidin is an effective love potion. Prior to mating, the male blister beetle squeezes cantharidin from his knees, rolls the sticky crystal into a ball and places it on his head for the female to sniff. If she likes what she smells, she will let the male mount her. She takes his cantharidin offering and smears it all over her eggs – the noxious chemical will effectively protect her unhatched offspring from being eaten. Males of a different species, fire-coloured beetles, also offer cantharidin to potential mates but don’t make it for themselves. If he is ever to persuade a female to mate with him, the fire-coloured male must trail the forest floor in search of a dead or dying blister beetle to lick.

And it’s not just humans and beetles that use cantharidin. Birds do it too. Nuthatches make nests in tree holes and commonly compete with squirrels for space. The birds have been seen grabbing blister beetles in their beaks and rubbing them around the entrance to their nests, presumably forming a barrier of squirrel repellent – not exactly what the beetles intended but ingenious nonetheless.

Today, cantharidin has been widely banned for human consumption but can still be found online and occasionally reports emerge of accidental Spanish fly poisonings.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Helen Scales giving us a reason to like beetles, through the chemistry of Spanish fly. Next week, size matters.

Andrew Holding

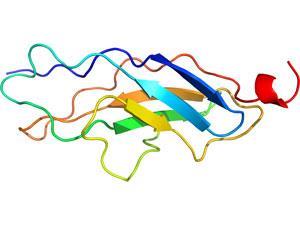

Titin is the largest known protein in the human body. That is not titin’s only achievement, though: titin’s official chemical name is a contender for the world’s longest word, with over 180,000 letters. So what does this super-sized protein do, and why does it need to be so big?

Meera Senthilingam

Discover that by joining Andrew Holding in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet