Meera Senthilingam

This week, Emily James sniffs out her favourite solvent.

Emily James

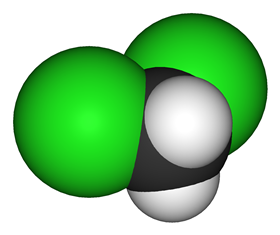

As an organic chemist, I’ve had a lot of exposure to organic solvents, especially the popular dichloromethane, also known as DCM or methylene chloride. Dichloromethane is a volatile, colourless liquid, with a mildly sweet, not unpleasant odour. It’s immiscible with water but can dissolve a wide range of organic compounds. These properties make it the perfect solvent for use in the lab, and indeed that how I used it - to separate and extract organic products.

But it’s not just useful in the lab; coffee, a very popular drink amongst researchers, was once decaffeinated using DCM. Unroasted beans would be steamed and then repeatedly rinsed in DCM, which would extract the caffeine. The solvent would then be drained away, leaving behind coffee beans packed full of flavour, but without the buzz. An alternative method was to essentially make a giant pot of very strong coffee, then extract the caffeine using DCM. When a new batch of beans was added to the brew, the higher concentration of caffeine in the beans would leach out into the water, decaffeinating the beans without removing any of the compounds essential to the flavour of the coffee.

DCM was the solvent of choice for caffeine extraction in the 1970s, however when it was found to be carcinogenic it was soon replaced by other non-toxic solvents. DCM is not only carcinogenic, but if it’s inhaled, it can also affect the central nervous system. On one occasion I was ‘extracted’ from the lab by my supervisor at the end of a long day, as my blushing cheeks and dazed expression revealed how productive I’d been with my own extractions.

Although DCM has a toxic dark side, it’s found a light-hearted use in a Chinese toy – the drinking bird

It was a good thing that she did tell me to take a (decaffeinated) coffee break - exposure can be fatal, with the most prominent symptoms being respiratory depression and narcosis. Due to its high volatility, toxic vapours can build up quickly in small spaces, such as bathrooms, if left unventilated. The solvent has unfortunately led to the deaths of several bathtub refinishers, who used DCM as an effective paint stripper. The enzyme Cytochrome P-450 also metabolises DCM in the body to produce carbon monoxide, which could potentially lead to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Although DCM has a toxic dark side, it’s found a light-hearted use in a Chinese toy – the drinking bird. The bird is made from a glass body containing dichloromethane - with two bulbs, representing the head and body, connected by a tube. Drinking birds are heat engines that use a temperature difference between the head and body to convert heat energy to mechanical work. This work takes the form of the bird tipping back and forth, just like it’s drinking from a cup of water.

Drinking birds have featured in many works of fiction to automatically press buttons or set off explosions. In The Simpsons episode ‘King-Size Homer’, Homer leaves a drinking bird in charge of safety at the nuclear power plant, by placing it in front of his computer keyboard while he irresponsibly goes out to watch a film. The bird repeatedly presses the ‘Y’ key to indicate a ‘yes’ in response to the computer prompts and almost causes a nuclear meltdown when it falls over and Homer isn’t around to pick it up.

If he had realised the bird’s peril, he would have balanced it back vertically on its pivot to start the tipping motion again. From this point, water from the bird’s head evaporates, lowering the temperature through the heat of vapourisation. The decrease in temperature causes the dichloromethane vapour in the head to condense, which reduces the pressure in the head according to the ideal gas law. The higher vapour pressure in the warmer base of the bird pushes dichloromethane up its neck, causing it to become top heavy and tip over into the traditional water source, or the keyboard in Homer’s case. The liquid is then displaced back into the base of the bird by the warm DCM vapour rising, thus returning the bird to its original position and the pressure back to equilibrium.

Dichloromethane plays an important part in the mechanism; its low boiling point means the drinking bird can function at room temperature. The bird can move even without a water source, like in the Simpson’s episode, – as long as the body is heated to a higher temperature than the head. Some people believe that the toy is a perpetual motion machine; however this is unfortunately not true, as it uses temperature gradients as an energy source.

So the next time you’re enjoying a cup of decaf, taking a bath or thinking about leaving a drinking bird in charge of your work whilst you sneak off on holiday, spare a thought for dichloromethane – the organic chemist’s favourite smelling solvent.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Emily James there with the odour-filled chemistry of dichloromethane. Next week, we switch senses from smell to sight and things begin to glow.

Brian Clegg

Of all the potential properties of a chemical substance, probably the most exotic is being able to glow in the dark. When radium was first discovered, its glow was a major selling point (until it was discovered to be deadly), and any compound that can produce a ‘cold light’ safely is bound to attract attention.

Meera Senthilingam

Discover which compound safely enables this by joining Brian Clegg in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet