Ben Valsler

We think of arsenic as a historical poison, preserved in Agatha Christie stories but otherwise confined to the past. But it still plays a role in modern medicine, as Gege Li explains…

Gege Li

What disease could be so bad that it involves a treatment containing arsenic? Although it’s best to avoid this notorious poison if you want to stay alive and well, there are times when it just might come in handy. Especially if you’re someone who’s been unlucky enough to have been bitten by a tsetse fly on your travels to tropical Africa.

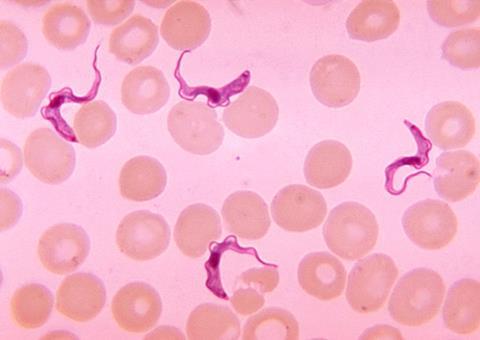

Also known as tik-tik flies, they carry a protozoan parasite called Trypanosoma brucei (shortened here to Tb) which causes the potentially-fatal disease human African trypanosomiasis, commonly called sleeping sickness. If left untreated, the disease can kill you in a matter of months, if it’s caused by the subspecies rhodesiense, or several years if it’s the more common Tb gambiense. That’s after a torrent of nasty symptoms like fever and headaches, followed by anemia, organ dysfunction and even paralysis and coma in the latest stages. It’s called sleeping sickness because it disrupts your normal sleep cycle, meaning you’ll unavoidably doze off throughout the day yet be wide awake come nightfall.

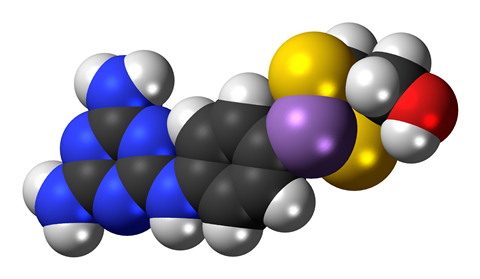

With the severity of the disease comes an equally severe treatment, which is where our deadly friend arsenic comes in – specifically, in the form of a drug called melarsoprol. Made by adding dimercaprol – a heavy metal chelator – to melarsen oxide, melarsoprol is able to cross the blood-brain barrier, so it’s mostly used for the secondary stages of Tb infection, when the central nervous system becomes compromised. Although it is toxic, with similar effects – unsurprisingly – to arsenic poisoning, it is nonetheless listed by the World Health Organisation (or WHO) as one of its essential medicines, something that might be to do with its success rate of curing 94 to 97% of people with sleeping sickness.

Melarsoprol is thought to work by binding to and inactivating pyruvate kinase, an essential enzyme in making life’s energy currency, ATP. The Tb parasite – called a trypanosome – is eventually killed when its energy supplies are diminished. But we can’t tune this action to target just Tb, so human ATP production is usually also affected, and could lead to life-threatening conditions like reactive arsenical encephalopathy, which can lead to coma.

To give an idea of how bad for you it really is (not that you really need it), intravenous administration of melarsoprol requires special plastic tubes that are strong enough to resist damage by the arsenic. And despite its impressive success rate, it can still kill 2 to 5% of patients – a decidedly shocking statistic in this day and age only permitted due to being approved 70 years ago before the full scale of its effects was known. Still, it’s a better option for those with the more fatal Tb rhodesiense infection than the other approved drug, eflornithine, which is much less toxic, but isn’t as effective a treatment. It is, however, very good at getting rid of excessive facial hair on women under its brand name Vaniqa.

Eflornithine itself has an interesting history, only coming into existence when scientists began to use rational drug design to develop drugs for cancer. The ‘resurrection drug’ is its otherworldly alter ego, so-named because it revived a woman from a sleeping sickness-induced coma in 1983.

Fast forward 35 years to 2018, and things are looking up for those who are most hard hit by the disease. The number of reported cases in Africa, where the tik-tik flies (and trypanosomes they harbour) are found, has dropped dramatically in recent years, estimated to be as much as 86% from 2000 to 2014. Perhaps that’s what has spurred the WHO’s aim to get cases of sleeping sickness down to less than 2,000 per year by 2020.

Whether they will reach that goal, which would mean sleeping sickness is a public health concern no more, only time will tell. But the ever-decreasing numbers are surely a promising sign. And despite all of its troubling traits, melarsoprol can take some of that credit.

Ben Valsler

Gege Li with the arsenic-based sleeping sickness medication, melarsoprol. Next week, Brian Clegg adorns himself with an ancient accent

Brian Clegg

There is surely a special place in any chemist’s heart for compounds that sound as if they’re straight off the pages of a comic book – and lazurite sounds as if it has to be something a supervillain uses to create a world-destroying laser. In reality, though it’s the secret behind many a pharaoh’s blue bling.

Ben Valsler

Join Brian next week. Until then, we would like to know if there are any podcasts you think are missing from our compound catalogue – get in touch by email to chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for listening.

No comments yet