Meera Senthilingam

This week, the medically beneficial chemistry of a compound notorious for its explosions. Blowing it up into the open, here's Peter Wothers:

Peter Wothers

Nitroglycerine is probably best known for its explosive properties, but it is also one of the first substances used successfully to treat the heart problem angina. This heavy colourless oil was first prepared in 1847 by the Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero who had worked under one of the pioneers in the chemistry of nitrocellulose, the French chemist Jules Pelouze. Sobrero called his new discovery pyroglycerine but was terrified of its explosive power and its extreme sensitivity, thinking it impossible to handle. But this substance proved to be exactly what was needed to turn around the fortunes of a Swedish family with a struggling explosives business.

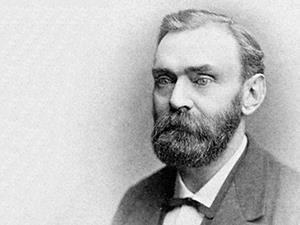

Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm in 1833 but when he was just five, his bankrupt father moved to St Petersburg in Russia to start a new company manufacturing explosives. Along with his brothers, young Alfred was educated at home by university professors and he soon became a most competent chemist.

Crucially, one of his teachers, Nikolai Zinin, had also studied under Pelouze in Paris. Perhaps it was through this teacher, or perhaps it was when Alfred also went to study under Pelouze, but at an early stage young Nobel became fixated upon nitroglycerine. He worked out a fairly reliable way to manufacture the compound, but his first great invention was the blasting cap that would ensure the complete detonation of the substance.

In 1863, at the age of just 30, Alfred patented Nobel's Blasting Oil, a mixture of nitroglycerine and black powder, a type of gun powder. This was soon demonstrated to be far more effective than normal black powder and construction engineers in particular valued it for its superior potential for blasting through rock.

However, the nitroglycerine was still incredibly dangerous to prepare and handle. In September 1864, a major explosion at his factory in Stockholm killed five people, including his younger brother. Further accidents followed all over the world: in November 1865, 'red fumes of an offensive smell' were noticed coming from a small box in the luggage room of the Wyoming Hotel in New York. It was thrown out of the window into the street 'where it immediately exploded with great violence'.

Much more seriously, the following April, 70 cases of the blasting oil spontaneously exploded at what is now Colon port in Panama with considerable loss of life. The explosion also destroyed the vessel containing the cargo together with the freight house, 400 feet of the quay and every pane of glass in the whole city.

With so many disasters, the use of the blasting oil began to be banned but Nobel responded with his second great invention: dynamite. This he discovered almost by chance when he noticed that some of the local earth where he was working easily absorbed the nitroglycerine to give a dry, workable paste, which would not explode without a detonator. It is this invention of dynamite, which he named after the Greek word for power, dynamis, that earned Nobel his considerable fortune. After his death in 1896, Nobel left this fortune to fund the world-famous prizes that have immortalized his name.

But even during his lifetime, nitroglycerine was already being used to save lives as a medicine. When first discovered, Sobrero had cautioned against tasting nitroglycerine since it invariably caused severe headaches. After hearing this news in 1849, the American homeopath Constantin Hering reasoned, following the homeopathic doctrine of 'like cures like', that nitroglycerine might also be able to cure headaches if sufficiently diluted. This eventually brought the explosive to the attention of more serious medics and in 1879 the English physician William Murrell published a report in the medical journal The Lancet, titled 'Nitro-glycerine as a remedy for angina pectoris'.

In his book published shortly afterwards, Murrell relates that the Chief Inspector of Explosives had said 'how he has often been struck by the extraordinary ruddy complexion of the women who work in the dynamite factory in Aryshire and their general appearance of stoutness and health, in fact a comelier lot of young women it would be difficult to find'. Perhaps it was this, together with other work on the related compound amyl nitrate, that prompted Murrell to use it to treat angina.

Of course, some patients were rather worried about taking a notorious high-explosive as a medicine. Nowadays, it is usually given the more accurate name of glycerol trinitrate, partly to allay such fears. But Murrell described being given a sample dissolved in fat on which he made numerous experiments without getting it to explode. He writes:

'It was placed on an iron plate, and a heavy weight allowed to fall on it from a considerable height. It was wrapped in paper and hammered for sometime on an anvil. It was stirred up first with a red-hot wire, and then with a lighted match, and was finally got rid of by throwing it out of a second-storey window!'

Nitroglycerine is still used today to treat angina and it is now known that it works by producing the powerful vasodilator, nitric oxide. In addition to treating heart problems under the trade name Zanifil, nitroglycerine has also recently ended up in condoms – perhaps for a more explosive performance. Exactly how nitiric oxide works as a vasodilator is still not entirely understood, but 'For their discoveries concerning nitric oxide as a signalling molecule in the cardiovascular system', the American scientists Furchgott, Ignarro and Murad were awarded the 1998 Nobel prize in physiology or medicine. I'm sure Alfred would have approved.

Meera Senthilingam

No doubt he would have, as these scientists increased the uses of this otherwise destructive compound. That was Cambridge University's Peter Wothers with the now-versatile chemistry of nitroglycerine. Next week, sunshine awaits and possibly some eye-watering moments.

Philip Robinson

It's the start of summer. The cold, dark winter is finally a distant memory and the sun has got his hat on. You step outside in bare feet for the first time this year, and then stop suddenly. What's that noise? Your neighbour's lawn mower?

If that realisation makes you freeze with fear, and then leg it to the bathroom to rifle through the medicine cabinet, you must be one of approximately 20% of the population that is predicted to suffer from hay fever at some point in their lives.

And the compound responsible for all your suffering? Well, that's histamine.

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out just how histamine causes these effects on the body join Phil Robinson in next week's Chemistry in it's element. Until then, thank you for listening. I'm Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet